I have been listening to the audiobook version of the new history, The Dawn of Everything, by David Graeber and David Wengrow. This is the most important non-fiction book I have ever read. I urge everyone who has any interest in history or politics to read it. The basic argument is that human polities were much more pluralistic and changeable in the past and that the present global political monoculture of class-based hierarchies enforced by bureaucratised violence is, in fact, an oddity rather than a forgone conclusion.

In Chapter 8, the authors briefly discuss the Indus Valley Civilisation. Listening to Graeber & Wengrow describe the place of the water tank in Indus civil architecture I was struck by parallels I had seen with my own eyes in India, but also have encountered many times in ancient Indian texts. Indeed, this is one of the most iconic images associated with India: a person who walks down into the river, performs ritual ablutions and prayers, and emerges a new person. I emphasise ritual here, because waterways in India are now so filthy, fetid, and toxic that one cannot imagine emerging from immersion cleaner than before. Students of Indian history will know, however, that while water is important in Vedic culture, fire is the element they worship more than any other. Where does river worship come from? Well, there was a river based civilisation in India long before the Vedic tribes started arriving. I'm certainly not the first to observe this, but I'm riffing on an idea here and won't refer to others much.

The Water Nation

The Indus civilisation (ca 3300 – 900 BCE) sprawled over the floodplain of the Indus and Sarasvatī Rivers, which consisted of numerous settlements including some large cities. Their economy was varied. They grew numerous crops including wheat, barley, peas, and sesame—as well as raising domesticated animals such as buffalo, zebu cattle, sheep, and goats. They mass produced stone tools and items such as pottery and beads. Moreover, they traded far afield, by sea, with Indus pottery being found in Mesopotamian and Arabian archaeological sites.

The two largest cities, Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, were built to a similar plan. And I say "plan", advisedly, because these cities were clearly designed. Roads were typically wide and straight and had built-in drainage. Indeed, drainage was an important feature of the cities, presumably to allow annual monsoon rain waters to escape the town (and at least in some places to channel them into storage tanks).

The cities have a raised central area that 19th Century archaeologists called "the citadel" that is surrounded by an urban sprawl of mixed-use housing and craft-based light industry (bead making, metal working, etc). Yet there are few other signs of social stratification. Finds of high status objects are evenly distributed, rather than being centered on the citadel (it was apparently not a place where material wealth accumulated). The citadels were walled, but these seem not to have been defensive walls (unlike the walled cities of the second urbanisation where warfare was a constant threat).

At the center of the big Indus cities we do find large scale public architecture: sizeable meeting halls and accommodation for the people who might meet in them, large buildings that appear to be granaries, and so on. Notably at Mohenjo-daro we find a large water tank at the centre, called "the Great Bath" by archaeologists. The water tank was constructed from well-made bricks and sealed with clay and bitumen. The tank is about 12 m x 7 m, and has a maximum depth of 2.4 m and has steps allowing access at either end.

"At Mohenjo-daro, it seems, the focus of civic life was not a palace or a cenotaph, but a public facility for purifying the body." (Graeber and Wengrow: 316).

And this is is significant to Graeber and Wengrow's argument that civilisation does not necessarily entail coercion and control. As I say, for me this evoked images and memories of watching Indian people perform their ritual ablutions in tanks built for the purpose, as well as in rivers.

I'm concerned that no parallel structures have been found elsewhere. It's a definite weak point in the thesis I'm outlining. The only consolation is that archaeology of the Indus Civilisation has barely scratched the surface.

Like the dozens of other Neolithic (recent "Stone Age") or Bronze Age settlements that mark the beginnings of civilisation, the Indus cities were sited on rivers. This is not simply to provide for potable water. In fact, each home in the Indus cities was supplied with a well for this purpose (and drains to allow waste water to escape). One of the advantages of living next to a river is that the water table around it is easy to get at. Well water is filtered through river sediments, mostly clay, and provides reliably clean water. The main advantage of riparian life, however, was transportation. Rivers were the highways of the ancient world.

It now seems very likely that before about 2000 BCE, another river paralleled the Indus but has since dried up due to a drier climate. In Sanskrit, this river is called Sarasvatī. At this time, prior to rapid weakening of the monsoon, the Yamuna flowed west into the Indus Valley and may have been a tributary to the Sarasvatī. Scientists have also made links to the Ghaggar-Hakra system which now flows into the Thar Desert and simply dries up (however, it was like this by the time of the composition of the Ṛgveda, ca 1500-1200 BCE).

We don't know, but can easily imagine that these water-loving people made gods out of the rivers that sustained their way of life. Did they worship the rivers we now call Indus and Sarasvatī? This seems highly likely to me. Michael Witzel has pointed out that, in the Ṛgveda, Sarasvatī is a river but also appears without connection to the eponymous river. At times Sarasvatī appears to represent the milky way (the galaxy that our star, Sūrya, resides in). This mixing of symbolism could be suggestive of two cultures hybridising.

Living next to a river that floods annually due to the monsoons is not always easy. I vividly recall driving over the long Mahatma Gandhi Setu (bridge) in Patna on our way to Bodhgaya. At that point in the dry season the Falgu River (the ancient Narañjana) had completely dried up. The Falgu has a bed that is over 500m across. The Ganga in Patna was about 1 km across, although the river bed is 2.5km wide at that point. The problem is that the flood plain is much wider so the bridge actually spans 5.7 km.

Alluvial soils are extremely fertile and allow for intensive agriculture. Some Indus cities had extensive earthworks designed to move water from annual monsoon floods into storage tanks (e.g. at Dholavira).

Towards the end, the Indus Culture was beset by drought as the climate changed, resulting in a weaker monsoon. If the monsoon fails, India starves. The Indus citizens moved away from cities altogether. This has been seen as a rout, with the citizens fleeing the cities and probably dying in great numbers, leaving chaos, but the Sarasvatī gradually dried up over some centuries, so this process was not sudden from the point of view of those living it. Reading Graeber and Wengrow it seems just as likely to me that, following some very disappointing results, the Indus people just decided to change the way they lived. They moved northwards towards abundant water in the river valleys closer to the Himalayas, what we now call Punjab (i.e. pañca āpas = five rivers). But they settled in village-style communities with a more distributed polity and no centralisation (which emerged later, partly in response to the challenge of Buddhism). There is now no reason to think that this was not a conscious move away from an unsustainable lifestyle towards a more sustainable one, given changing conditions over many generations.

In other words we must not think of the people who lived in massive planned cities as idiots, as naive, or as passive. These were active people, who built great cities, who tamed the monsoon floods and channeled them into agriculture. We have to assume that they discussed what was happening at length and consciously decided how to survive the extended drought and, just as when they built the cities, put a plan into action.

In any case, according to Romila Thapar "The Ṛgveda lacks a sense of civic life founded on the functioning of planned and fortified cities." (2002: 110). Nor do we see elements such as elaborate drainage systems, or the use of fired bricks. It seems clear that the authors of the Ṛgveda did not know of the urbanised Indus Culture at all. What they met in India was a culture of distributed autonomous villages. They settled in this area, which they called the "Āryavrata", the area in which Ārya customs prevail) or the Kurukṣetra (Field of the Kuru), the Kuru being one main faction of the myths in the Mahābhārata, the other being the Paṇḍava.

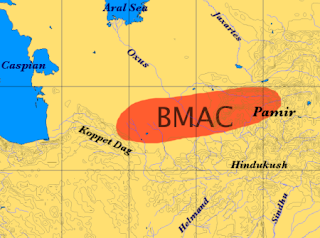

During this same period we have another culture emerging on the other side of the Hindu Kush. Archaeologists have called this the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (or BMAC) or Oxus Civilization, since it is associated with the Amu Darya (which imperialists named the Oxus River following Greek historians) which flows north into the Aral Sea. Recent work dates occupation of the area to c. 2250–1700 BC.

Goods found in the archaeology tell us that the two cultures were aware of each other and trade between them took place. But they were genetically distinct with little sexual mixing between cultures.

This civilisation spoke an Indo-European language, and is possibly the place where Indo-Iranian split off and became a distinct branch of the family tree, though evidence for language in the ancient world is very limited. Archaeologists believe that the BMAC culture was the forerunner of the so-called Āryans, who split off from the general Indo-Iranian culture ca 1900-1700 BCE and eventually introduced their language and culture into India. While Indo-European languages came to dominate India, genetics tells us that in fact the Āryans were few and mainly men. Max Müller's "Āryan invasion", in which the Āryans were a large invading army, has long been deprecated, though the idea continues to exercise nationalists in India. Still, Indo-European influences were absent from India until the people who spoke Vedic arrived.

Incidentally, the story of the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain has gone the same way: there was migration, but not enough to overwhelm the local population. Most white British people have a genome that is predominantly of the same stock as Celtic peoples in Britain and Europe. What differentiates them is that, following the departure of the Romans after almost 400 years of occupation, the thoroughly Romanised British adopted the language (Old English) and customs of a minority group of immigrants from Northern Germany. Europeans have been coming and going from the British Isles since they could walk across Dogger Bank (end of the last ice age) because the land here is extremely fertile, and the winters are much warmer than in Europe because of the gulf stream.

The BMAC culture had domesticated horses from the steppes and wheeled carts. Most strikingly for us the BMCA architecture is built around temples in which fire was either worshipped or was a ritual medium for the expression of religious ideas. Background fire worship in Iran was absorbed into and became a feature of Zoroastrianism:

The Greeks, too, had a cult of the hearth fire, and although Herodotus (3.16) mentions the great veneration in which the Persians held fire, he does not single them out as being in any remarkable way “fire-worshippers,” nor does he know of temples of any kind among them (1 .131). A Zoroastrian temple cult of fire seems to have been first instituted in the later Achaemenid period [4th century BCE], being probably established by the orthodox as a counter-move to the innovation of a temple-cult, with statues of “Anāhīt.” (Encyclopedia Iranica)

Keep in mind that Herodotus (484 – 425 BCE) was reliable enough that later historian, Plutarch (46 – 119 CE), dubbed him "the father of lies". Since the yasna rituals "are essentially those of the Brahmanic yajña [i.e. fire-based ritual], the yasna evidently goes back to the proto-Indo-Iranian times." (Boyce 1997: 12)

Zoroastrianism also had a tradition of itinerant priests known as aθauruuan or āθravan (Old Iranian θ approximates Old Indic th). The similarity of Avestan āθravan and Sanskrit atharvan is striking. Strabo uses the term āθravan to refer to "fire keepers". The Atharvans (Pāḷi ātabbaṇa) seem to be distinct from the Brahmins and had their own sacred text, the Atharvaveda (though it has considerable crossover with the Ṛgveda). But the Atharvans are seen quite negatively; for example, early Buddhist texts paint them as evil and depraved magicians. Herodotus also mentions the Magi ("may guy"), one of six Iranian tribes, who "specialized in hereditary priestly duties and who assumed the duties of the athravan." (Zoroastrian heritage). My suspicion is that the Atharvans were the Āθravan.

The dates of Zarathustra are uncertain but likely to be around 1000 BCE ± 200 years. Records of the Zoroastrian religion are preserved in the ancient Avesta, which must have been roughly contemporaneous with the Ṛgveda (ca.1500 – 1200 BCE), which just fits within one end of the proposed date range for Zarathustra. Meanwhile, in India, fire worship morphed into Brahmanism and gave rise to the Ṛgveda. It appears that the ṛk "verses" were composed by men sitting around a fire taking a psychoactive compound that made them feel imaginative and heroic (the most likely candidate being an extract of Ephedra sinica), telling fantastic stories in metred verse about the Gods, especially Indra, Varuṇa, and Mitra (Avestan Miθra). The central concern of this stories is the maintenance of ṛta conceived of as a kind of cosmic harmony or balance operated by the gods who could be compelled by ritual to tip things in favour of "us" (whoever "us" might be). This theme of cosmic harmony is notably absent from European myth though it is present in Chinese myth (I make no claim here, I merely note the similarity of ṛta and dào 道).

In Parthian Iran (247 BCE – 224 CE), fire temples were constructed with a square base surmounted by a dome, the result looks uncannily like an old Buddhist stupa.

|

| Bazeh Khur Fire Temple, Khorasan Parthian era 247 BCE-224 CE. |

|

| Buddhist Stupa Swat Valley, 1st-2nd Century CE. |

A Confluence of Cultures

It is quite clear that the slow end of the Indus Civilisation was not the end of the Indus people, per se. They had a radical change of lifestyle and they did move upriver, but they persisted, with worship of rivers and daily ablutions forming a central part of their culture. It seems very likely, almost incontrovertible, that these were the people living in Panjab when Indo-Europeans started settling in the region.

As already noted, an influx of settlers does not constitute an "invasion", nor does the influx have to become a majority in order to effect massive social and political changes. The Romanised Celts of Britain voluntarily adopted the language and culture of a Germanic minority. Nor does it mean that the locals are hapless victims. Trade goods have been moving in both directions along the Khyber Pass for millennia, with trade connections as far afield as the Arabian peninsula. As with early Britain, people moved around a lot more during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Still, there are no signs of large scale migrations in the region. There was a small influx of (mainly male) Indo-European genes into India from Iran during the Bronze Age and a century or two later the resulting hybrid culture produced the Ṛgveda.

Analysis of the language of the Ṛgveda suggests early contact with a culture that spoke a language related to Muṇḍa, a branch of the Austro-Asiatic family of languages that includes modern Vietnamese, Khmer, and Mon. Michael Witzel (1999) has suggested that the source of Muṇḍa loan words was the remnant population from the collapse of the Indus cities, which seems entirely plausible to me. There are also Dravidian loan words, but Witzel argues that pattern of loanwords in Ṛgveda points towards initial contact with Muṇḍa and only later with Dravidian.

Linguistic features such as retroflex consonants, absent from Indo-European languages generally, appear in Vedic from our earliest records. Madhav Deshpande has referred to these as "regional" features, that is features of the subcontinent, rather than any particular culture. Indeed, they appear to increase in frequency from the older books of Ṛgveda to the younger.

Despite absorbing external influences, the Ṛgveda is still recognisably Indo-European and Vedic is obviously very closely related to Avestan and other Indo-European languages of the day. It seems that an existing culture was impressed enough by the Vedic-speakers to have adopted their language and customs creating a hybrid. We have to assume, following Graeber and Wengrow, and as appears to have happened, that this was a conscious decision.

The confluence of the water nation and the fire nation gave rise to a unique culture. the mature form of which is associated with Painted Grey Ware pottery in the late Iron Age (1200 - 600 BCE). The PGW culture produced a distinctive grey pottery and is associated with permanent village settlements, domesticated horses, and metallurgy (gold, silver, copper, iron). Note that Atharvaveda mentions iron, but Ṛgveda does not (and we need to be wary of arguments from absence as they are often weak unless there is an overriding expectation of presence).

We should also note that as far as Buddhist texts were concerned there were two main kinds of Brahmins: householder Brahmins who often attracted large groups of followers; and ascetic Brahmins, who often adopted jaṭila or dreadlocks (as they still do). Pāli suttas record kings granting land to Brahmins, whole villages it seems, which suggest that they were actively recruiting Brahmins to migrate to their kingdoms. Brahmins were often valued political advisors and royal ritualists (purohita). In particular, Brahmins had a panoply of lavish large-scale public rituals aimed at legitimising the power of the king (and all rulers who wield power over other humans need some justification for doing so, because we all instinctively hate being given orders).

Signe Cohen has conjectured that part of what drove the composition of the Upaniṣads was a conflict between conservative Brahmins from the Āryavrata and progressive Brahmins who had begun migrating east (into the world of the early Buddhists). The word āryavrata can be compared to the term Danelaw, it is the region where the customs (vrata) of the Ārya are upheld. Brahmins consciously referred to themselves as ārya (a word cognate with modern name for Persia, i.e. Iran or Īrān).

We tend to massively over simplify Indian history because we have just two literary sources: Vedic and Buddhist. Jains have been around as long, but their extant literary tradition dates from a later period. Jain tradition says that the first generation of texts was lost. Loads of other people were around, they just left no literature. We have to look to the archaeology and what it can tell us about this period.

Archaeology and linguistic evidence point to multiple communities speaking languages from at least three distinct language families: Muṇḍa, Dravidian, Vedic, along with an unknown number of minority languages. Note that some tribes in central India, until recently living a hunter gatherer lifestyle, speak in languages unrelated to any known language. This suggests a deep antiquity for these cultures, perhaps on the the scale of Australian Aboriginals, i.e. tens of thousands of years.

The hegemonic Vedic culture in India is clearly an amalgam of Indo-European and indigenous influences. A mix of Water Nation and Fire Nation.

~~oOo~~~

Attwood, J. (2015) "Who Were the Artharvans?" Jayarava's Raves 10 July 2015.

Boyce , M. (1997). "" In Companion Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy, edited by Brian Carr and Indira Mahalingam, 4-20.

Clift, P. D., Carter, A., Giosan, L et al. (2012) "U-Pb zircon dating evidence for a Pleistocene Sarasvati River and capture of the Yamuna River." Geology 40 (3): 211–214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/G32840.1

Graeber, D. & Wengrow, D. (2012) The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. UK: Allen Lane.

Khonde, N., Singh, S.K., Maurya, D.M. et al. (2017) "Tracing the Vedic Saraswati River in the Great Rann of Kachchh". Nature: Scientific Reports 7, 5476 . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05745-8

Mahoney, William K. (1998). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. State University of New York Press.

Thapar, Romila. (2002). The Penguin History of Early India: From Origins to AD 1300. Penguin Books.

Witzel, Michael. (1999) Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Ṛgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic). Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies (EJVS) 5(1): 1–67.