Sangharakshita wrote his magnum opus, A Survey of Buddhism, in 1954. In the second chapter he explained how the Bodhisattva Ideal represents a unifying ideal for Buddhism. However as time went on Sangharakshita's thinking on this subject developed. In the History of My Going for Refuge he describes how he came to see the act of Going for Refuge as constituting the fundament Buddhist act. Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels - the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha - is common to every school and sect of Buddhism. Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels, then, is not only fundament it is also universal and hence is more clearly the unifying factor in Buddhism. Sangharakshita sees the Bodhisattva Ideal as the altruistic dimension of Going for Refuge.

Sangharakshita wrote his magnum opus, A Survey of Buddhism, in 1954. In the second chapter he explained how the Bodhisattva Ideal represents a unifying ideal for Buddhism. However as time went on Sangharakshita's thinking on this subject developed. In the History of My Going for Refuge he describes how he came to see the act of Going for Refuge as constituting the fundament Buddhist act. Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels - the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha - is common to every school and sect of Buddhism. Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels, then, is not only fundament it is also universal and hence is more clearly the unifying factor in Buddhism. Sangharakshita sees the Bodhisattva Ideal as the altruistic dimension of Going for Refuge.The language of Going for Refuge is not Buddhist in origin. Like many things in Indian religion it has a Vedic origin. The Chāndogya is one of the oldest upaniṣads and almost certainly pre-Buddhist. In Chapter four it instructs the one carrying out a sacrifice to go for refuge to the verses (i.e. mantra) and the way they are chanted, to the direction one is chanting in, and in Atman. [verses 8-12]. However it was adopted by the Buddhists very early. Right from the first the people who met the Buddha told him that they would go for refuge to him and his Dharma.

It's important to note that we do not take refuge, we go to it. That is to say that Going for Refuge is an active seeking, not a passive hiding. Neither can an unenlightened being 'give' us refuge. When we go for refuge to the Sangha, it is not simply to other Buddhists, or to monks, that we Go for Refuge, but to the Awakened Sangha, to the ones who have directly seen the Truth for themselves.

Over the centuries Buddhism has become very diverse. Schools of Buddhism struggle to recognise each other as Buddhist. Buddhism, like other India religions, is inherently syncretistic - rather than suppress heterodoxy, it embraces it. Buddhists have never hesitated to borrow from other traditions. As Buddhism was exported from India it interacted vigorously with the other cultures and languages it met. Most of Asia was transformed by Buddhism, but from place to place that transformation took radically different forms.

As a result we now have a bewildering variety of Buddhisms (plural) each with their own set of practices, their own jargon, mother tongue, scriptures, and cultural expressions. There have been many misunderstandings, and some reactions against fellow Buddhists, sometimes from unexpected quarters.

Sangharakshita treats Going for Refuge as a hermeneutic which we can apply to any person in order to relate to them as fellow Buddhists. Because Going for Refuge is fundamental and universal we have a key to understanding what other Buddhists are doing. One of the examples that Sangharakshita uses is the case of Pure Land Buddhists who do not believe that any self power will avail them in Awakening, and that they must rely on other power in the form of the vows of Amitabha. To attitude stands in something of a contrast to most forms of Buddhism which exhort us to generosity, ethical behaviour and meditation - i.e. to a vigorous application of self-power. At first sight we might not see how simply chanting the name of Amitabha can really be considered a Buddhist practice. Surely it is just a form of theism? If we apply Sangharakshita's key then we first look to see whether the Pure Land Buddhist is going for refuge and to what. In this case they are clearly going for refuge to the Buddha in his Amitabha form. Their practice is to develop faith in the vows of Amitabha to save beings from suffering. This makes sense in the light of their Going for Refuge to Amitabha.

Over the years many different texts and interpretations piled up. Earlier versions of the Dharma were not discarded, but placed on a lower level. The typical response to this was to create a hierarchy of teachings - this tendency was present even in early Buddhism. By the second millennium CE the hierarchies had become very elaborate and unwieldy. But how else were Buddhists to make sense of texts which contradicted themselves and were polemical against earlier forms of Buddhism? Again Sangharakshita's hermeneutic can help us, especially if we combine it with an historical over-view of the development of Buddhism. If we view all practices as motivated by Going for Refuge, and aimed at Awakening, and then we take account of the historical development of texts and exegesis, then we need not stack forms of Buddhism vertically, preferring one over another.

Sangharakshita recently said to a group of new Dharmacaris, that he sees nothing in the Vajrayana which goes beyond the Theravada or Mahayana at their own pinnacles. What I think he means by this is that later practices are not more effective than earlier ones. Some practices may be better suited to some people than others, but all practices will only be effective to the extent that they are whole heartedly practised. To put it another way, the practice will be as effective as the Going for Refuge of the practitioner. There is a strong tendency amongst Buddhists to see their own school, or sect, or group, as being the best, the highest form of Buddhism. This kind of thinking obscures the unity of Buddhism.

Buddhism is a highly diverse and heterogeneous religion. The unity of Buddhism is in the act of Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels. By seeing all Buddhists and their practices in terms of Going for Refuge that we can see how they relate to us and our practice. This also enables us to avoid the false conceit that we are on a better path, or that we are doing more powerful practices.

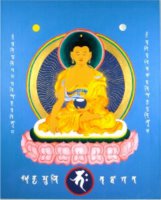

image: Śakyamuni Buddha, by Jayarava.