I recently had an email from someone who read my Wikipedia article on Shingon and wanted to know more about it. (Had a look at the article recently and didn't recognise most of the text but that's the Wikipedia for you). I explained to him that I had read everything I could get my hands on, and I had done detailed study of Kukai's writing, but that I did not practice Shingon Buddhism, and therefore couldn't offer much more than what was in that article. My correspondent was interested in what I meant when I said "I practice the Dharma". Amongst Buddhists this kind of throw away line would probably not even get a second thought. We all assume we know what someone means by that kind of statement. But how do you explain it to someone who might not share your jargon or assumptions.

I recently had an email from someone who read my Wikipedia article on Shingon and wanted to know more about it. (Had a look at the article recently and didn't recognise most of the text but that's the Wikipedia for you). I explained to him that I had read everything I could get my hands on, and I had done detailed study of Kukai's writing, but that I did not practice Shingon Buddhism, and therefore couldn't offer much more than what was in that article. My correspondent was interested in what I meant when I said "I practice the Dharma". Amongst Buddhists this kind of throw away line would probably not even get a second thought. We all assume we know what someone means by that kind of statement. But how do you explain it to someone who might not share your jargon or assumptions.So I started thinking about what I meant when I said I practice the Dharma. At first I was tempted to go into complicated answers that involved lots of doctrinal categories: the path of ethics, meditation and wisdom was an early starter. But then I realised that this would just be gobbledegook to anyone without a few years of reading the same books as me. And unlike my knowledge of Shingon, my Dharma practice is not just book learning.

I do a variety of more formal Buddhist practices: meditation, puja, study, reflection, chanting, right-livelihood etc. But this wasn't going to be much use because each one of these exists in a context which requires explanation. So I started stripping things back to essentials. What is it that I am doing in all of these formal practices, and in the many informal practices I do?

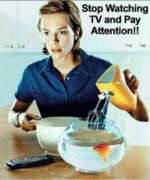

And it came to me that what I do is I try to pay attention to things. This is the guts of what I wrote in an earlier post about my approach to the six perfections. From that perspective I pay attention to other people, to our mutual impact on each other. This produces not only a change in behaviour which promotes awareness, but also liberates energy. Then I can start paying attention to my own mind through meditation. Finally I can begin to pay attention to the nature of reality.

Another approach to this might be to start from my basic desire for happiness. This is something we all have. Even if, like me, we're not always sure we deserve happiness, we still want it. It goes beyond self-esteem and self-views. From this point of view what I am doing as a Buddhist is looking closely at the kinds of things that conduce to happiness and which don't. I also try to note how long that happiness lasts. For instance, a certain amount of dark chocolate does indeed make me feel happy and secure and less anxious. It really works. But it's a short lived happiness. And then there is the anxiety that I will run out of chocolate and the shops will be shut and I'll get a headache because I haven't had my fix lately. Now at present I might not be ready to stop eating chocolate as an antidote to anxiety, but I can still pay attention to the process. I can still observe the cycling between anxiety, eating, happiness, rising anxiety until the desire to eat is triggered again.

So, it became clear that what I do as a Buddhist is I try to pay attention to things, to my mental and emotional states, to other people, and to the real nature of reality. Which sounds a bit simplistic doesn't it? I mean what about the whole edifice of teachings, the profound philosophical doctrines, and, since I'm interested in Shingon, the initiations and lineages. I'm by no means finished thinking about all of this, but it strikes me that all of the superstructure of Buddhism is just an increasing elaborate way of making us pay attention. My impulse is to simplify things, to cut away all of the extrusions and look for what is essential.

In any case it's clear to me that one cannot simply take the Buddhist tradition on it's own terms. I've written about this as well in The Unity of Buddhism. Each strand of traditional Buddhism sees itself as the pinnacle, and other as provisional at best. This is alright when strands exists in relative isolation, but in the present we have access to so many of the strands, each with their unique contribution that it doesn't make sense to privilege one over the others.

The one major objection that I have come up with to this train of thought is that attention is an ethically neutral function. We can pay attention to unethical things as much as ethical. Just paying attention might not actually be enough. It might be necessary to add some qualifier. There is actually a traditional precedent for this - the Pali texts tell us to avoid ayoniso-maniskara, unwise attention.But again I think if we simply pay attention to the consequences of paying attention then it will become clear what things are better to focus on. This was the point of my essay on Imagination. It may be that we need to be reminded of the need for kindness, for kindly attention, from time to time.

It is possible that we might seek our own good at the expense of others. But if we are paying attention to others then we will be aware that they are suffering as a result of something we have done. I find this a very uncomfortable awareness. So if I am paying attention it seems unlikely that I could be happy by exploiting someone else. My happiness is tied up with the happiness of those people around me, and ultimately with all beings.

So what I mean when I say I practice the Dharma is: I pay attention to things. Simply that. And it has been very fruitful to date.