|

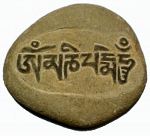

| mani stone visiblemantra.org |

The earliest text which contains the most famous of all mantras is the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra. The title means "the casket containing the magnificent array", with the implication that it is the magnificent array of Avalokiteśvara, the Bodhisattva associated with the mantra.

Alexander Studholme has challenged the view that the Kāraṇḍavyūha is a very late and corrupt Mahāyāna text, and established that the Kāraṇḍavyūha is likely to have been written in Kashmir in the late 4th or early 5th century. This is by no means early in the development of the Mahāyāna and post dates the emergence the main themes such as Madhyamika and Yogacara, but not so late as previously thought.

The Kāraṇḍavyūha shows definite Puranic influences, especially from the Skanda Purāṇa of the Śaiva tradition. The Kāraṇḍavyūha, for instance, re-presents material from the Śaiva version of the story of the Vāmana-avatāra of Viṣṇu. Vāmana is a dwarf who asks a king for land. The king grants as much land as he can pace out in three paces. Vāmana transforms himself into a giant and covers the whole earth in one pace, and all of heaven in the second! In the Skanda Purāṇa this is presented as a morality play to encourage generosity, and so it is in the Kāraṇḍavyūha. Also in the Kāraṇḍavyūha, Avalokiteśvara appears as a bee in imitation of story about Śiva. Studholme says: "The sūtra clearly reflects a close interaction with a non-Buddhist religious milieu that is predominantly Śaivite, but one which is also respectful of the Vaiṣṇavite tradition." [1] His conclusion is that while the evidence of direct borrowing is limited and relatively weak, the evidence for influence and interaction is indisputable.

In the Kāraṇḍavyūha Avalokiteśvara is portrayed as Iśvara or Lord, and this is a title particularly associated with Śiva. Avalokiteśvara is also addressed as Maheśvara - Great Lord - three times. Several times Avalokiteśvara is described as the cosmic puruṣa which is a reference to the Puruṣa Sukta from the (Ṛgveda X.90). In a related text Avalokiteśvara is described as Nīlakaṇ(ha - blue throated - another of Śiva's epithets. Although Avalokiteśvara appeared well before the Kāraṇḍavyūha, for instance in the 24th chapter of the Saddharmapuṇḍarika Sūtra which may date back to the 1st century BCE, in the Kāraṇḍavyūha he seems to be consciously being given the attributes and names of Śiva. Avalokiteśvara's thousand armed form has Vedic and Puranic precedents despite the fact that no images of this form have been found on Indian soil - although Chinese images existing as early as the 7th century.

This ambiguity is heightened by Studholme's presentation of information about the very name Avalokiteśvara. The much later verse version of the Kāraṇḍavyūha may be the source of the explanation of Avalokiteśvara as "the lord (iśvara) who looks down (avalokita)" which has become the standard way of glossing it. However Studholme notes that before the 7th century the name seems to have been different. In fact the standard Chinese rendering Kwan Yin (觀音) is not a translation of Avalokiteśvara, but of Avalokitasvara which we would translate as he who is aware (avalokita) of sounds (svara). Avalokiteśvara in Chinese would be Kwan tzu-tsai (觀自在). The fact Kwan Yin has been retained as the popular name of Avalokiteśvara in China suggests it was well established before the change. This usage is confirmed by 5th century fragments of the Saddharmapuṇḍarika, and is used in various Chinese translations and dictionaries. [2]

How did Avalokiteśvara take over Śiva's name and qualities? It is indicated symbolically in the sūtra itself where the two figures meet and Avalokiteśvara congenially converts Śiva to Buddhism. Later, in the Sarvatathāgata-tattvasaṃgraha Tantra, this story becomes a violent confrontation where Vajrapaṇī and Śiva have a battle of magic (through mantras) and Śiva is first killed, and then revivified before converting to Buddhism. We can read this as an admission that yes, the sūtra is borrowing from the Śaivite tradition, but that it is being converted to Buddhism. Studholm shows that the Kāraṇḍavyūha, and the intended use of the mantra, are entirely consistent with the mainstream of Mahāyāna Buddhism.

This type of assimilation and adaptation was the norm in India rather than the exception, and should come as no surprise. Buddhism was no different and many borrowings from Vedic tradition are to be found in the earliest scriptures. The goal of using these forms is two-fold. It is likely that the authors of the Kāraṇḍavyūha were seeking on a purely social level to make converts, to compete with the majority Hindus, and to reinvigorate their own spiritual milieu. On the other hand, the broad goal of Buddhism, i.e., the liberation of beings from suffering, is still uppermost in their minds.

The Kāraṇḍavyūha shows a concern for the upholding of the institutions of celibate monasticism; however, in order to get the teaching of the mantra, monks venture outside the vihara to visit a man who is married with a family, does not keep the precepts, and is dirty. Studholme likens him to a tantric yogin, or a siddha, although the wife and kids really don't fit this picture. In any case, the teaching comes as part of a teaching which involves a mandala (with Amitabha in the centre) and an initiation. Despite all of these references to, and borrowings from the Śaiva tradition. However the Kāraṇḍavyūha "presents the practice [of chanting the mantra] primarily within a scheme borrowed from the bhakti side of the Purāṇic tradition". [3] By this he means that the Kāraṇḍavyūha chiefly presents chanting the mantra in terms of the Pure Land tradition - one calls on the name of a Buddha and is reborn in a pure land (in this case it is one of the worlds which are found in the hair pores of Avalokiteśvara, but which are effectively identical to Sukhāvatī). Contrast this with the traditions which draw on the "śakti" side of the tradition, in which the mantra is part of a ritual magic which transforms the practitioner into a Buddha. Studholme makes no comment on the relation of the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra to the, by then, centuries old dhāraṇī tradition which is a shame.

Oṃ manipadme hūṃ, then, emerges from interactions between monastic Buddhists and lay Hindus in 4th or 5th century Kashmir. The religious goal of these Buddhists is conceived in terms of rebirth in a pure land, not in tantric terms.

To see the oṃ manipadme hūṃ mantra in a variety of scripts see visiblemantra.org.

Notes

- Studholme p.34.

- You can see this for example in English translations from the Chinese version. Of the three that I could lay my hands on easily all were translated from Kumārajīva's 406 version and the name of Avalokiteśvara is translated by Bunnō as Regarder of Cries of the World; Watson as Perceiver of the World's Sounds; and Hurvitz as He who observes the Sounds of the World - all translations of Avalokitasvara. Hurvitz includes a comparison with the Sanskrit version of the sūtra where the name Avalokiteśvara is used alongside his translation of Avalokitasvara without comment.

- Studholme p.103.

Studholme, Alexander. 2002. The origins of oṃ manipadme hūṃ : a study of the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra. Albany : State university of New York Press.

It must be said that this book is an academic text which often labours a point beyond the patience of a general reader, and that it is full of jargon. By which I mean no disrespect for Alex, who was pleasantly surprised when I asked him a question on his book at a public talk and then asked him to sign my copy (a first apparently). It's just that the book is not an introduction to the mantra, but an in-depth study for specialists. Some Sanskrit would be an advantage reading this book.

~~oOo~~

Note 8 Sept 2014

On the name of Avalokiteśvara in Chinese see also: Jan Nattier. 'Avalokitesvara in Early Chinese Buddhist Translations: A Preliminary Survey.' Proceedings of the 5th Chung-Hwa International Conference on Buddhism. Dharma Drum, 2007.

Also note that despite the widespread perception of the meaning of ava√lok spread by Edward Conze it does not mean 'looks down' but 'examines'. See my later essays on the Heart Sutra for more on this.