The average Buddhist reader has a naive approach to Buddhist texts. At worst we take them at face value as being what the texts themselves say they are: the actual words of the Buddha. At best we are slightly suspicious about translations, and might compare more than one when studying a text.

The average Buddhist reader has a naive approach to Buddhist texts. At worst we take them at face value as being what the texts themselves say they are: the actual words of the Buddha. At best we are slightly suspicious about translations, and might compare more than one when studying a text.We all interpret texts. The study of the methods we employ when we read a text, the presuppositions and assumptions we bring to text, and the ideas that underlie how we understand a text, is known as Hermeneutics. The hermeneutic we employ in reading a text, or what we believe the text to represent even, determines to a large extent what we understand a text to be saying. As an exercise in this post I'm going to write about some of my working assumptions in reading a Buddhist text.

I am strongly influenced by contemporary Buddhology. For instance on the basis of scholarship - linguistic, historical, and text critical - I do not believe that the words preserved in Buddhist texts can have been literally spoken by the historical Buddha. The evidence is overwhelmingly that the Buddha did not speak Pāli or Sanskrit or any of the other languages in which texts are preserved. Therefore the texts have been translated at least once. Equally I do not accept that all of the teachings literally came out of the mouth of one person. The Buddhist doctrine evolved over time and new ideas and practices were added at each step along the way. Clearly some texts were written after the lifetime of the Buddha (I do accept the high likelihood of there having been a historical Buddha).

The Buddhist texts were preserved as an oral tradition for several centuries, and there is little or no evidence for the use of sophisticated mnemonic techniques as used by the Brahmins to preserve the integrity of the text. Also as you read the texts it's clear that some passages have been inserted rather crudely by some later editor. Presumably other more skilled editors were at work. Then there are differences between the Pāli texts and surviving parallels in other languages. Comparing the Pāli and Gāndhārī Dhammapadas for instance one can immediately see that they are far from identical. Some doctrines have been played down by some schools -0 such as the practice of mettā in Theravada. So Buddhist texts can not have the status of divine revelation.

One problem that emerges out of assuming that all the teachings came at once is that there are contradictions. In attempts to resolve these difficulties Buddhists have historically had to make some teachings provisional, and others ultimate. But this is problematic because each text proclaims itself to be the ultimate and final teaching of the Buddha, only to be superseded as something new emerges. The centuries have left us with many unstable towers of texts each one claiming to be the final teaching. Sangharakshita has said that there are no higher teachings, only deeper realisations. Following Sangharakshita I think it is time to dismantle the hierarchies of value and accept that texts emerged over time. If a text is profound, then it is profound. The fact that some later disciple wrote it on the basis of their own experience should not lessen it's value. in other words are we interested in truth or lineage?

Another important aspect of my hermeneutic is that I see texts as idealised. Texts are unreliable guides to history because they are what some people thought the ideal was at some point in time. We need an historical perspective which is not available from the texts themselves in order to fully appreciate that this is so. Greg Schopen for instance, in a long career of iconoclastic debunking of sacred cows, has emphasised the point that epigraphical and archaeological evidence often provides flat contradictions to the texts. Monks not only frequently handled money, for instance, but in at least one case actually printed it! Generally speaking we could say that a text represents the social and spiritual ideal as it was conceived by a particular community at the time it was written. The Pāli commentaries to the Suttas for instance tell us more about Buddhism in 5th century CE Sri Lanka, than they do about 5th century BCE India. They are still useful for understanding the texts they comment on, especially in terms of philology, but must be read cautiously for historical value. In fact some scholars have concluded that Buddhist texts have nothing useful to say about the history of Buddhism. This is going too far I think, but highlights the dilemma.

Many scholars now point to influences in the Buddhadharma. It seems pretty clear that many early Buddhist teachings are in response to Brahminical and Jain religious discourse for instance, and that Tantric Buddhism was in dialogue with Śaivism. I have found one or two examples of this myself, but Prof. Richard Gombrich has lead the scholarly investigation of the sources of the Buddha's ideas. Some concepts can't really be understood without reference to Vedic or Vedantic doctrine. The clearest example of this ātman (Pāli attā) which has it's roots in the general religious discourse of the day, a discourse which is seldom if ever replicated in the modern West. This should not be confused with the early 20th century idea, also popular with Hindu scholars, that Buddhism is a kind of reformed or even unreformed Hinduism. The point is that the Buddha responded to his audience which was frequently deeply versed in Vedic lore. He had to communicate in terms which would be understood by his audience - though he frequently redefines words as he goes. But there are also examples of Buddhist and Hindu texts (for example the Dhammapada and the Mahābharata) which draw on a common pool of religious or moral stories. Aspects of the Pāli canon, the obvious worship of yakṣas for instance do not seem especially Buddhist, but relate to what the people around the Buddhists believed.

We must also remember that Indian religious traditions interacted in a way that it quite foreign to the West. In an earlier post [Religion in India and the West] I compared the Indian religious attitude to the Microsoft business model. Each Indian tradition has adopted and adapted ideas from the others. Where one tradition begins to dominate, the minority religions will borrow their ideas, symbols, and practices. During the time when the Tantra emerged amongst the ruins of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century, many different traditions were synthesised into a grand new pattern incorporating various strands of Buddhism, Vedic ritual, Śaiva ritual and iconography, Vaiṣṇava devotional practices and so on. Westerners have tended to characterise this as a degeneration. Contemporary scholarship has exposed the origins of this attitude in Protestant criticisms on the Catholic church based on the model of the Roman Empire. In fact Tantric Buddhism was a much needed revitalisation of Buddhism, but one which may have had too little influence on mainstream Buddhism to save it from collapse. The decline of Buddhism is often attributed to the invasion of Islamic forces from Persia, but they were only the final nail in the coffin of a moribund institution. The vigour of Tantric Buddhism is obvious in Tibet. In Japan Tantric Buddhism dominated for 400 years, but was eclipsed to some extent by indigenous forms such as Zen and Jodo Shin Shu - although not many people know that Shingon is still the largest Buddhist sect in Japan.

Finally I would say that over recent times I have become increasingly suspicious of translations. Translations often hide a multitude of sins. There are huge problems with representing the intellectual content of Buddhism in English. English language and culture is vastly different from Indian. Often the connotations of an English word used as a translation of a Buddhist technical term are entirely unhelpful. For instance it is quite misleading to translated Dharma as "Law", but this frequently happens. The translator must make a large number of discriminations and decisions in translating a text. Just as in English a word in Pāli or Sanskrit may have a range of meanings (polysemic). Some words are highly polysemic and deciding which of sometimes a dozen or more potential senses are indicate depends on how well the translator knows the language (and English), how deeply they understand the Dharma, and

We need also to be aware that what is available in English translation is not the entire corpus of Buddhist texts. While the Pāli canon has been translated more or less entirely, the older translations are unreliable. In the case of Māhayāna Sūtras we have only a small proportion in English. It is most likely that this has skewed our understanding of the development and emphases of the Mahāyāna. [see also Which Mahāyāna Texts?] Many scholars think for instance that the influence of the White Lotus Sūtra in India was negligible, and that it is a rather idiosyncratic text.

I hope that all of this skepticism does not add up to cynicism. But it's clear that I express a lot more doubt about the provenance of texts and the uses that they are put to, than most of my peers and colleagues. I find that I continue to be fascinated by Buddhist texts and textual studies. I have also found that my studies inform and enrich my practice of Buddhism. I suppose I want to call for an intelligent and informed approach to texts. I am far more intellectual than most of my peers and don't expect them to adopt my rather intellectual approach, but I do hope that if you've read this then you might spend a bit of time examining your beliefs about the texts. Where do your beliefs come from, and on what are they based? Are their elements of blind faith in there for instance? It's good to be aware of biases, of likes and dislikes, and to see how they operate to shape your experience of the world.

Often we are looking for certainty and there is a lingering desire for the texts to be the Absolute Truth (paramartha satya). This is both generally true of humans, but especially true in the post-christian west where ideas of absolutes, and concrete answers remain in our psyches. Since Absolute Truth cannot be summed up or put into words we should be at least a bit suspcious of texts. What words are good for is giving us the recipe. They cannot give us the experience of eating the cake.

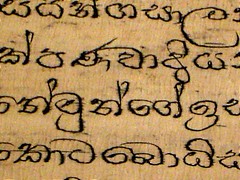

image: Sinhalese Buddhist text. Jayarava on Flickr.