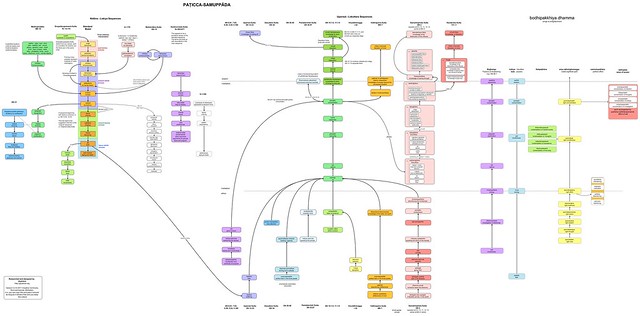

THIS IS A DIAGRAM showing the Canonical variants of paṭicca-samuppāda in both its lokiya (left) and lokuttara (middle) forms along with the bojjhaṅgas or factors of awakening (right) which have some cross-over. The lokiya being more usually know as the 'nidānas', or in the Triratna movement the 'cyclic nidānas'. The lokuttara known as the 'Spiral Path', the 'positive nidānas', or 'progressive conditionality'. I have started calling them the upanisās and hope to popularise this. I constructed this diagram because I like to think visually - certain relationships are easier to see graphically - and because I had some new (free) software to play with in the form of the Visual Understanding Environment. If you click on the image you can see the full sized version which is 7578 x 3591 px.

When paṭicca-samuppāda is taught in traditional circumstances it is typically not this very complex view that is taught. What is taught is a synthesis which irons out all of the complexity and condenses all of the variation into the standard 12 nidānas, and usually leaves out the upanisās all together. Even in the Triratna Order, which emphasises the upanisās as being of central importance, we only teach the version found in the Upanisā Sutta (SN 12.23).

This raises two questions I think. Firstly why is the canonical account of paṭicca-samuppāda so complex, and even contradictory? Secondly, why is the presentation of paṭicca-samuppāda so simplified and coherent?

I can think of several reasons why paṭicca-samuppāda might be complex. Both scholars and buddhists believe that paṭicca-samuppāda is a general principle which can be expressed in a variety of ways. The general principle is that 'things' arise in dependence on conditions. I've critiqued this view (see A General Theory of Conditionality? and Paṭicca-samuppāda: a Theory of Causation?), but in the end I think it is inevitable that we see the general nature of the principle of conditionality. And any general principle can be illustrated using a variety of concepts, images and metaphors. So we might expect to find complexity. There is also the generally acknowledged idea that the Buddha responded to individuals, explaining things in a language, and at a level, which they could understand. This might explain some of the variation, and a certain amount of contradiction. The Buddha had the goal of liberation in mind, but allowed for any number of paths to get there. Anything which conduces to liberation is Dharma! (see What is Buddhism?) Some of the contradictions are in the order of development in the morality part of the upanisās section of the diagram. These don't amount to show stoppers, but are just different ways of presenting the dynamics of morality. I've confessed to other confusions concerning the lokiya side of things which I think are more serious problems with the model.

Another reason for complexity is that the composition and transmission of these texts, and their collation into a Canon, took place over several centuries. It also seems likely that variations emerged in different communities - what we might these days call transmission lineages. Evidence for these lineages can be found where the same story occurs in different versions. Look for instance at the story of Vaseṭṭha and Bharadvaja in DN 27, MN 98, and Sn 3.9 (and compare with DN 13 as well) - these suggest to me one story remembered different ways. Some scholars (especially Tillman Vetter, following Eric Frauwallner) have speculated that the 12 nidānas were originally two sequences that that have been joined together. One of the supporting observations they make is that there are several Canonical sequences that begin with taṇha (e.g. SN 12.52), though to suggest that this is somehow 'original', rather than merely fragmentary is actually quite doubtful - especially in light of all of the other fragments of doctrine floating around the Canon! Joanna Jurewicz and Richard Gombrich have suggested that especially the first four of the 12 nidānas were added to a shorter sequence in order to satirise Vedic cosmogony because these terms have a particular resonance for Brahmins [1]. This idea of historical process may be the only way to make sense of the various fragments, or sequences that skip steps.

The complexity of the Canonical accounts of paṭicca-samuppāda are comprehensible, and even predictable under the circumstances. But why has the tradition condensed all this to a single set of 12 nidānas, ignored variation and dropped the upanisās all together?

Obviously it makes teaching about paṭicca-samuppāda a lot easier to present it in a simplified version. The discussion of all of the variations is time consuming and is potentially confusing. So there are didactic or pedagogical reasons for beginning with a simple version. I don't understand, however, why the simple version became the only version. If the tradition goes to all the trouble to preserve this vast corpus of literature, why did it lose interest in the detailed content of that literature? After the synthesis produced by Buddhaghosa there seems little interest in critical scholarship in the Theravāda until the modern era, and that was stimulated by the Western critical traditions. And in the Mahāyāna they seem to be immersed in sorting out the significance of their own doctrinal innovations to pay much attention to these basic issues. We seem to have mistaken the map for the territory at some point.

One of the interesting quirks of history is the complete loss of the upanisā sequence in received traditions. Though the sequence occurs once in the Visuddhimagga (Vism i.32) it is given no prominence. As far as I know it does not feature in Mahāyāna texts at all, nor in contemporary Theravāda presentations of the Dhamma. [2] Sangharakshita speculates that it was a preference for via negativa arguments - what he polemically calls "one-sided negativism" [3] - that the upanisā sequence was lost sight of, but in fact we do not know the answer to this conundrum. The full recovery of the teaching has not yet been completed either, because all present published accounts of the upanisā sequence rely on the Upanisā Sutta (SN 12.23) and as I argue in my essay on the upanisā sequences (Onramps to the Spiral Path - pdf) this sutta is not representative of the other Canonical accounts.

It also seems that one of the functions of religion is to provide some certainty, or at least the illusion of certainty. A nice, simple model of reality suggests that life or the universe is actually simple and that certainty is possible. Presenting a simplified model as a beginning is fine, however in many quarters the knowledge that it is only a simplified model seems to have been forgotten. I suggest that this is a symptom of not studying our own texts - we tend to take our knowledge of Buddhism from contemporary accounts of commentarial traditions, precisely because they are simplified and easier to understand. Most people do not seek complexity, they seek simplicity; and most of us are uncomfortable with uncertainty.

Complexity is difficult to communicate or understand. One of the best ways for dealing with complexity is to look for patterns. So in the diagram above we see that many factors repeat in the various schemes, and that they clump together in related categories: many of the elements are to do with morality for instance, while others are related to meditation. So we describe the complex situation in simpler terms - the threefold path of morality, meditation and wisdom is one useful scheme for organising the complexity we find in the Pāli Canon. This is technically called a reductive explanation - and most Buddhist doctrine is highly reductive. It is important to remember that a reductive explanation only simplifies the explanation for the purposes of communication, it does not reduce the phenomena in any way. Ironically, there seems to be a prejudice against reductionism amongst many Buddhists, perhaps because of a tendency to forget about the distinction I've just made. Every conceptualisation involves some reduction of complexity, and Buddhism as communicated in texts is always reductive, always trying to communicate meaningfully about the complexity of human experience, through simplifications, generalisations, and broad categories. This is not a problem unless we take the reductive explanations literally. As Alfred Korzybski said: the map is not the territory.

Books and articles are still being written about the Dharma to supplement a commentarial tradition stretching back in all likelihood to the time of the Buddha himself. Contemporary scholars have yet to reach a full consensus regarding the complexity of the nidāna sequences, but the complexity of the upanisā sequences has received almost no scholarly attention. My own essay on the upanisā sequence is not intended for an academic audience, but aims to provide a scholarly account for the Triratna Order (I reference in-house documents and discussions that would no doubt be disqualified in an academic journal). The idea of lokuttara paṭicca-samuppāda is still mostly a lost idea.

~~oOo~~

Notes

- Joanna Jurewicz's idea is summarised in chapter 9 of Richard Gombrich's book What the Buddha Thought

. I think Gombrich overstates the importance of Jurewizc's discovery. It is interesting, but it's not obvious that the sequence was formulated primarily as a parody. There is unexplored complexity here!

- There are two exceptions that I know of. Bhikkhu Bodhi wrote Transcendental Dependent Arising (1980) in response to Sangharakshita's The Three Jewels.

Ayya Khema wrote about the Spiral Path in When the Iron Eagle Flies (1991) and, as she was a personal friend of Sangharakshita, I suspect she also got the idea from him.

- Sangharakshita (1993) A Survey of Buddhism. 7th ed., Windhorse, p.136.

The latest version of the diagram is on my dependent arising webpage, where you can also find partial versions of the diagram, and some other essays. I've printed it on A1 paper, and it is just readable. A0 would be better.

I

I