THE URBAN MYTH that the Nazi swastika goes one way, but the sacred symbol of India goes the other way seems to still be current. Sadly, this is not true. The official National Socialist Worker's Party emblem, adopted in 1932, was the clockwise swastika, and this is often seen on Buddhist images as well. Jains even use the rotated svastika. Both clockwise and anticlockwise are used in Indian religious iconography, and both are found, for instance, in the Tibetan Unicode block: U+0FD5 卐 (right-facing/clockwise), U+0FD6 卍 (left-facing/anti-clockwise). The svastika is also a Chinese character, and is pronounced wàn. If you look at Google maps of Japan you'll see temples marked with the 卍.

In the Western world the swastika - the lucky symbol of India - seems indelibly associated with Nazism. Articles entitled "The Swastika and X" continue to be produced, and all of them examine aspects of Nazi Germany. There's some irony here as the Germans did not call it a swastika but a hakenkreuz 'hook cross' and elsewhere it is referred to as a Greek Cross. In China the association of the symbol with the Falungong movement has caused the Chinese government to react against it as well. [1]

Perhaps because of the Nazi connection in the early 20th century, it seems that Victorian Era sources are largely responsible for forming our views of the symbol. Most sources seem to recycle opinions first articulated in the mid to late 19th Century. In researching the subject I turned up a reference to Cunningham (1854) in The Migration of Symbols , by the wonderfully named Eugène Goblet d'Alviella (1894, but still in print) which also refers to a letter Max Müller wrote to Henry Schliemann and was published in Schliemann's book Ilios (1880). [2] These sources, with Monier-Williams's Sanskrit English Dictionary, seem to account for most of what's on the Internet in English. Note that the Oxford English Dictionary suggests it came into use in English only in 1871, but Cunningham (1854) trumps this, and this is a rare case of the OED being wrong!

, by the wonderfully named Eugène Goblet d'Alviella (1894, but still in print) which also refers to a letter Max Müller wrote to Henry Schliemann and was published in Schliemann's book Ilios (1880). [2] These sources, with Monier-Williams's Sanskrit English Dictionary, seem to account for most of what's on the Internet in English. Note that the Oxford English Dictionary suggests it came into use in English only in 1871, but Cunningham (1854) trumps this, and this is a rare case of the OED being wrong!

Despite the negative association in modern times the bent cross symbol appears in many disparate cultures around the world, and throughout history. The symbol is found in Indus Valley seals for instance (pre 1700 BCE), and has been used by Indigenous North Americans, and pre-Christian Europeans including Greeks and Celts. Goblet d'Alviella (1894) seems to see the ubiquity of the symbol as evidence of a single ur-culture that migrated around the world. Many explanations are found for the symbol - that it is a solar symbol, perhaps via a wheel symbol; that it originates in weaving societies, etc. In India, by the time we have good records for it, the svastika is simply a superstitious lucky symbol with no definite underlying symbolism.

The Wikipedia swastika page perpetuates another urban myth about the svastika that can be traced to General Sir Alexander Cunningham via the Monier-Williams Dictionary (1899). MW says s.v. svastika (p.1283a):

"...according to the late Sir A. Cunningham it has no connexion with sun-worship but its shape represents a monogram or interlacing of the letters of the auspicious words in the Aśoka characters."

MW supplies no reference for this claim, but it is repeated across the Internet, and in a variety of otherwise reputable sources. A bit of detective work shows that Cunningham, later the first director of the Archaeological Survey of India, makes the claim in: The Bhilsa Topes (1854). Cunningham, surveyed the great stupa complex at Sanchi in 1851, where he famously found caskets of relics labelled 'Sāriputta' and 'Mahā Mogallāna'. [3] The Bhilsa Topes records the features, contents, artwork and inscriptions found in and around these stupas. All of the inscriptions he records are in Brāhmī script. What he says, in a note on p.18, is:

"The swasti of Sanskrit is the suti of Pali; the mystic cross, or swastika is only a monogrammatic symbol formed by the combination of the two syllables, su + ti = suti."

There are two problems with this.

While there is a word suti in Pali it is equivalent to Sanskrit śruti 'hearing'. The Pali equivalent of svasti is sotthi; and svastika is either sotthiya or sotthika. Cunningham is simply mistaken about this.

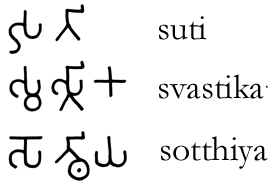

While there is a word suti in Pali it is equivalent to Sanskrit śruti 'hearing'. The Pali equivalent of svasti is sotthi; and svastika is either sotthiya or sotthika. Cunningham is simply mistaken about this.- The two letters su + ti in Brāhmī script are not much like the svastika. This can easily been seen in the accompanying image on the right, where I have written the word in the Brāhmī script. I've included the Sanskrit and Pali words for comparison. Cunningham's imagination has run away with him.

Below are two examples of donation inscriptions from the south gate of the Sanchi stupa complex taken from Cunningham's book (plate XLX, p.449). Note that both begin with a lucky svastika.

The top line reads 卐 vīrasu bhikhuno dānaṃ - i.e. "the donation of Bhikkhu Vīrasu." The lower inscription also ends with dānaṃ, and the name in this case is perhaps pānajāla (I'm unsure about jā). Professor Greg Schopen has noted that these inscriptions recording donations from bhikkhus and bhikkhunis seem to contradict the traditional narratives of monks and nuns not owning property or handling money. The last symbol on line 2 apparently represents the three jewels, and frequently accompanies such inscriptions.

The word svasti (स्वस्ति) is a feminine noun probably deriving from su- + asti: where su- is a prefix cognate with the European eu- meaning 'good, well, excellent' and asti is from the verb √as 'to be'. Perhaps through constant use the word asti, originally the 3rd person singular present of √as, came be an indeclinable particle meaning 'existent, being'. Sandhi rules mean that su+asti becomes svasti which means 'well-being', and is used in the sense of 'auspicious, good fortune, luck, success, and prosperity'. In other words svasti is rooted in ancient Indian superstition. Note that in all modern transliterations of Sanskrit व is written va. So how do we come to spell our word swastika with a 'w'? There could be for two reasons: firstly modern Hindi and other North India IE languages transliterate व as wa, and we could be taking the word not from Sanskrit, but from Hindi; secondly Cunningham (back in 1854) was transliterating Sanskrit व as wa as well and other Victorians might have followed suit. The suffix -ka is adjectival and so svastika (स्वस्तिक) should mean something like 'related to well-being'. However in this form we would normally expect the root vowel to change to its strongest (vṛddhi) grade svāstika, and this does not happen in this case.

Müller (in Schliemann, p.346-7) notes that svasti occurs throughout 'the Veda' [sic; presumably he means the Ṛgveda where it appears a few dozen times]. It occurs both as a noun meaning 'happiness', and an adverb meaning 'well' or 'hail'. Müller suggests it would correspond to Greek εὐστική (eustikē) from εὐστώ (eustō), however neither form occurs in my Greek Dictionaries. Though svasti occurs in the Ṛgveda, svastika does not. Müller traces the earliest occurrence of svastika to Pāṇini's grammar, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, in the context of ear markers for cows to show who their owner was. Pāṇini discusses a point of grammar when making a compound using svastika and karṇa, the word for ear. I've seen no earlier reference to the word svastika, though the symbol itself was in use in the Indus Valley civilisation.

Müller says that the svastika only refers to the right-facing cross 卐, while the left-facing cross 卍 is called sauvastika, and incidentally does not believe that the symbol is a monogram (Schliemann p.347). [4] The form sauvastika doesn't make sense to me. If the root vowel underwent vṛddhi (a > ā) then the word would be svāstika; but there are a number of words in MW which have this change: sva > sauva. If it is su undergoing vṛddhi (prior to combining with asti) then the form ought to be sāvasti (su > sau and au + a > āva). If sauvasti is the vṛddhi form, then we'd expect the weakest grade to be suvasti, but it is not. Others also insist on this difference between the two forms, but my impression of looking at Buddhist art is that no differentiation is made by artists. The BBC h2g2 webpage on svastika suggests that the distinction between svastika and sauvastika only dates from the 19th century, though the claim is not referenced. Sauvastika occurs in Sanskrit dictionaries, but not in relation to the symbol - a sauvastika according to Boehtlingk is a Hauspriester eines Fürsten 'The house priest of a prince'. MW suggests 'benedictive, salutary; family Brahmin'.

I would end by saying that the svastika is an element of pan-Indian superstition - a lucky sign. As such we should probably not mourn too much that it was taken over by the Nazis and given an indelibly negative connotation in the West. As modern, Western Buddhists we don't need lucky symbols, and we don't rely on luck. We practice. The svastika is really of historical interest only and there is no pressing need to rehabilitate it.

~~oOo~~

Notes

- Craig S. Smith, "In China's Religious Crackdown, An Ancient Symbol Gets the Boot," Wall Street Journal 8 September 1999, p. B1;

- The relevant page references in the online version of Goblet d'Alviella (1894) are incorrect. I have located printed copies in the Cambridge University Library, and supplied correct references in this article.

- This story is well recounted in Allen (2002) - see esp. p.214f. I recommend this book. I gather from a brief conversation I had with Charles, last year at a lecture by Prof. Gombrich, that his next book will be on King Aśoka which I'm eager to read.

- Goblet d'Alviella (1894, p. 46) appears to use Müller's remarks to contradict Cunningham, but in Schliemann (1880) Müller specifically refers to the Sanskrit spelling, not the supposed Pali of Cunningham. So the two statements are not really connected.

Bibliography

- Allen, Charles. (2002) The Buddha and the Sahibs. London : John Murray.

- Cunningham, Alexander. (1854) The Bhilsa topes, or, Buddhist monuments of central India : comprising a brief historical sketch of the rise, progress, and decline of Buddhism; with an account of the opening and examination of the various groups of topes around Bhilsa. London : Smith, Elder. [possibly the earliest recorded use of the word swastika in English].

- Goblet d'Alviella, E. (1894) The Migration of Symbols. London: A. Constable and Co. Online: http://www.sacred-texts.com/sym/mosy/index.htm

- Monier-Williams, Monier. (1899) A Sanskrit-English dictionary : etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to cognate Indo-European languages. [New ed. greatly enlarged and improved with the collaboration of E. Leumann, C. Cappeller and other scholars.] Asian Education Services : New Delhi, 2008.

- Schliemann, Henry. (1880). Ilios : the city and country of the Trojans : the results of researches and discoveries on the site of Troy and through the Troad in the years 1871-72-73-78-79. London : John Murray.

I

I