|

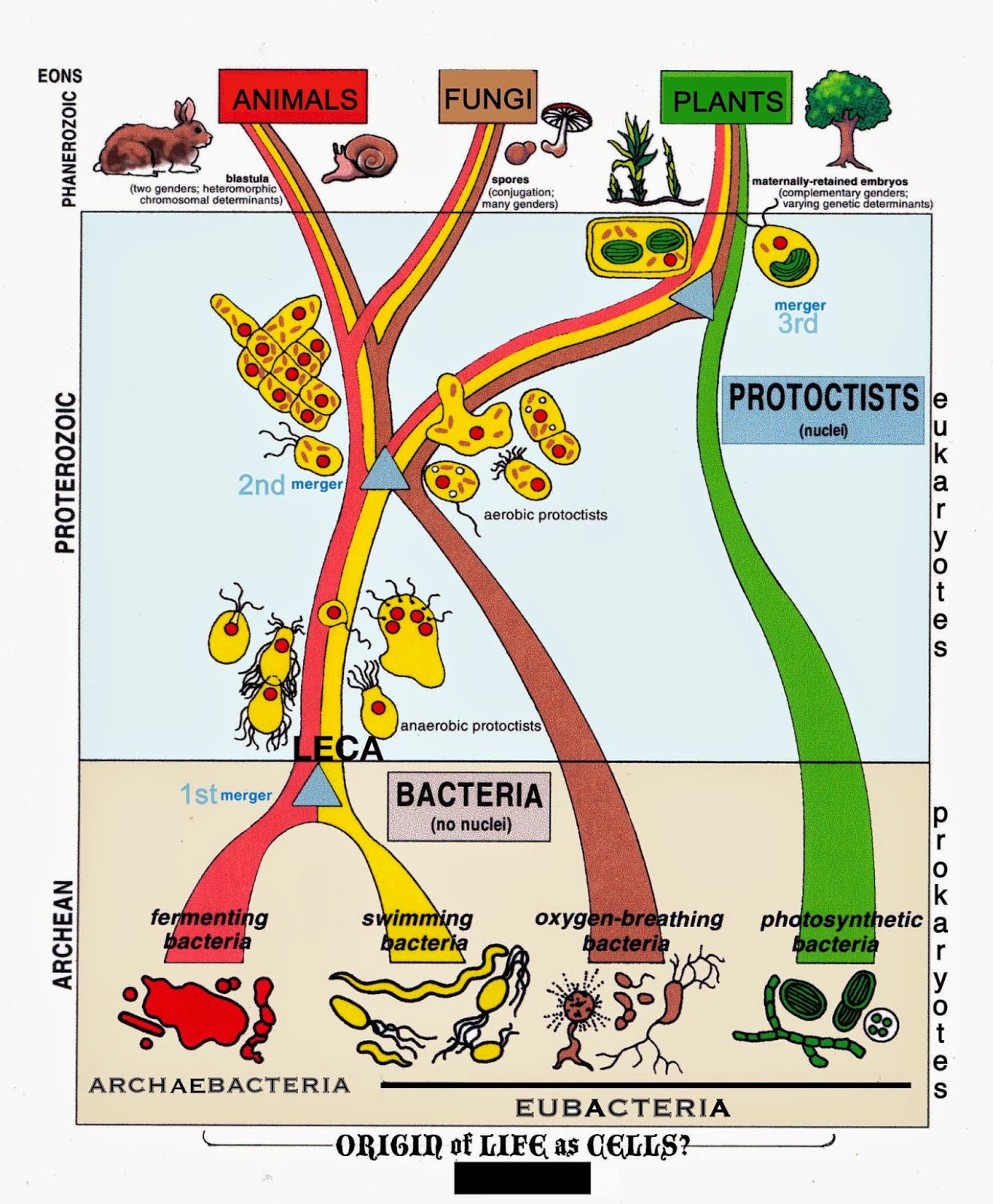

| Endosymbiosis according to Lynn Margulis. |

It's Endosymbiosis I want focus on in this essay. Endo means 'internal' and symbiosis means 'living together' and the compound refers to the fact that each of our cells is in fact a community of bacterial cells living together. This idea was first floated in the early 20th Century by a Russian scientist, Konstantin Mereschkowski. His observation concerned the green parts of plants. Seen under a microscope the plant resolves into uncoloured structures which support small green pills called Chloroplasts. These are very similar to cyanobacteria or blue-green algae and he conjectured that their might be a relationship. In the 1920s another scientist named Ivan Wallin made a similar identification between mitochondria (the oxygen processing parts of our cells) and other kinds of free living bacteria.

However the watershed event for endosymbiosis was the publication, after considerable difficulty with the establishment journals, of this paper:

Sagan, Lynn. (1967) 'On the origin of mitosing cells.' Journal of Theoretical Biology. 14(3) March: 225–274, IN1–IN6. DOI: 10.1016/0022-5193(67)90079-3

This rightly famous paper is now copied online in many places. Lynn Margulis had married Carl Sagan young and subsequently reverted to her maiden name for most of her career. So we'll call her Margulis, even though she was Sagan at the time. Incidentally Margulis was a collaborator with James Lovelock and a major contributor to the Gaia Hypothesis.

Margulis's mature theory goes like this. The first cells were bacterial. They had no nucleus, DNA in loops that could be shared with any other bacteria, reproduced by simple division, and no internal organelles with membranes. Bacteria are able to live in colonies with loosely symbiotic relationships, some are multicellular through their life cycle, but at some point one bacteria engulfed another, or one invaded the cell of another, and the result was not digestion or infection but symbiosis: a mutually beneficial relationship with one bacteria living inside another. Margulis argues that the complex cells of all plants and animals (called eukaryote) are the result of at least three symbiosis events in the past, with the photosynthesising chloroplasts of plants being a fourth. The resulting eukaryote cells are large, have a nucleus and other internally bounded organelles (particularly mitochondria) and reproduce sexually (they divide their DNA and allow it to recombine with half the DNA of another individual to produce variety). Eukaryote cells don't just form colonies, but collectively form multicellular organisms with a high degree of morphological specialisation.

The paper by Margulis led to the theory of endosymbiosis finding a firm footing and eventually to the idea being included in biology textbooks. However the establishment was and to some extent still are reluctant to follow up the implications of this discovery. NeoDarwinians treat Endosymbiosis as a one-off event 3 or 4 billion years ago with little relevant to evolution in the present.

But consider this. Every sperm is very like two kinds of organism. On one hand they are like certain type of motile bacteria with a single flagellum (a rotating 'tail') that propels them through the liquid environment. On the other hand a sperm is rather like a virus, which Margulis conceived of as a bacteria from which almost all the biological functionality had been stripped out: a virus is nuclear material with a basic mechanism to inject it into the host cell. A sperm travels to its target like a motile bacteria. When it meets an ovum it bonds with the outer surface and injects its DNA into the egg, like a virus. That DNA is transported to the nucleus to form a complete set of chromosomes and the cell is "fertilised". It begins to grow and divide almost immediately. Sperm are also unusual in that production of them requires lower temperatures than any other cell type - we males have to maintain a separate cooler environment for sperm production. So part of the complex human life-cycle is lived as a cross between a motile bacteria and a virus which prefers cooler temperatures. Each fertilisation event is an example of Endosymbiosis. If we don't have endosymbiosis at the forefront of our minds, we cannot understand the basics of reproduction.

Endosymbiosis is the most significant event in the history of evolution since life began. It ought to inform one of the fundamental metaphors for how we understand our universe, but instead we have competition, selfishness and treat the predator as totem. I hate to say this, but it all sounds a bit masculine, don't you think? We we might just have easily focussed on the combinative, symbiotic, collective aspects of life. So why don't we?

Endosymbiosis is the most significant event in the history of evolution since life began. It ought to inform one of the fundamental metaphors for how we understand our universe, but instead we have competition, selfishness and treat the predator as totem. I hate to say this, but it all sounds a bit masculine, don't you think? We we might just have easily focussed on the combinative, symbiotic, collective aspects of life. So why don't we?

Evolution and Empire.

Margulis speculated in interviews that the reason her idea was so difficult to get published and the establishment was so reluctant to take it seriously, was to do with Victorian attitudes amongst the mainstream (mainly male) proponents of evolutionary theory. The maxim of evolution is "survival of the fittest", coined by Herbert Spencer and adopted by Darwin in later editions of On the Origin of Species. By this Darwin apparently meant "the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life" (Darwin Correspondence Project). In this section I want to look at the historical context for this maxim.

Britain and various European powers had fought repeated wars over many centuries, but with the opening up of Asia and the Americas, trade was making Europe seriously wealthy at the expense of their colonies. The British, perhaps more so even than their European neighbours, developed a sense of superiority. The decisive battles involved in defeating Napoleon at the beginning of the 19th century left Britain in almost total control of the world's sea lanes and trade routes. This cemented a victory in the long running trade wars between expanding European Empires and accelerated the growth of wealth in the UK. Investment money poured into technological innovations that turned the industrial tinkering into the the Industrial Revolution. The great symbol of the British Empire is found in Trafalgar Square in London. There Admiral Nelson is celebrated by a very ostentatious, and very costly monument: a statue set on a towering column supported by four enormous bronze lions. Less obvious are the aisles of St Paul's Cathedral which are lined with statues of military heroes rather than saints, something that shocked me when I first arrived in this country but now makes perfect sense: church, mercantile sector, state and military are all aligned here.

Darwin, Spenser and a previous generation of thinkers such as Jeremy Bentham (father of utilitarianism) and Adam Smith (humans primary motivation is self-interest) were writing at a time when Britain was the world's only super-power and it was busily using that advantage to exploit the entire world for individual profit. Even the peasants of England were exploited. The newly rich forced the enclosure of common lands for example, in order to both become more wealthy, but also to keep pressure on peasants to stop them revolting. Britain was, and to a great extent still is, a deeply hierarchical society dominated by a few wealthy and powerful families. Everyone is expected to play the social role they were born into, though anyone can aspire to be middle class these days because that threatens no one (except some of the middle class).

Darwin, Spenser and a previous generation of thinkers such as Jeremy Bentham (father of utilitarianism) and Adam Smith (humans primary motivation is self-interest) were writing at a time when Britain was the world's only super-power and it was busily using that advantage to exploit the entire world for individual profit. Even the peasants of England were exploited. The newly rich forced the enclosure of common lands for example, in order to both become more wealthy, but also to keep pressure on peasants to stop them revolting. Britain was, and to a great extent still is, a deeply hierarchical society dominated by a few wealthy and powerful families. Everyone is expected to play the social role they were born into, though anyone can aspire to be middle class these days because that threatens no one (except some of the middle class).

Back in the 19th Century Charles Dickens chronicled this way of life and the baleful influence it had on the less fortunate. Another contemporary, Karl Marx, saw the system for what it was and wanted to completely replace it. What has changed since Dickens and Marx is the rise of the middle class: a class of people whose main function is to manage and facilitate the wealth making activities of the wealthy. They do so in exchange for lives of relative comfort and security (compared to the poor) but seldom make enough money to escape the need to work for a salary for the best part of their adult lives. Averages salaries are about 1% of the earnings of their company's CEO and a tiny fraction of the actual profits of the company. Religion is still the opium of the people, but the middle classes oversee the production of the empty calories and mindless entertainment that are the crack cocaine of the people.

Thus for members of the landed gentry, such as Spenser and Darwin, it was only natural that they subscribed to the theory that nature favoured some members of a species above others. Some were destined to succeed and dominate the herd. It was at heart a notion that justified their position both in British society and the dominance of the British internationally. They and their whole class saw themselves as the fittest to rule. This attitude persists in Britain and is on open display in today's government. The members of government have hereditary privilege and wealth and often title as well. They see themselves as the natural leaders and arbiters of morality. In other words there is a political dimension to Darwin's ideas. We cannot understand the development of mainstream science of evolution without understanding this political dimension.

A key NeoDarwinian figure like Richard Dawkins is very much a product of the British class system: born to a Civil Servant father who administered a colony (Kenya); educated in a private school, followed by Balliol College, Oxford University; eventually becoming a "Don" at Oxford. There's no doubt that the boy was bright, but he was a member of a privileged class and as such had opportunities no ordinary British person would have, even now. And the vision of his class is basically the Victorian one. The Selfish Gene is essentially the Victorian gentleman's values expressed as an ideological view of genetics. Dawkins repeated says that the Selfish Gene is only a metaphor, but it is a metaphor for, even an apology for, the values of the British upper-classes as much as it is a metaphor for evolution. We can see that being enacted even today in the policies of conservative governments. Dawkins basically recapitulates Adam Smith's idea that each individual striving for their own benefit is the best way to benefit society. He even argues that this is the best way to understand altruism!

Compare Adam Smith

Compare Adam Smith

"Every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it ... He intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for society that it was no part of his intention. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good." An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. 1776With Richard Dawkins:

"The argument of this book is that we, and all other animals, are machines created by our genes. Like successful Chicago gangsters, our genes have survived, in some cases for millions of years, in a highly competitive world. This entitles us to expect certain qualities in our genes. I shall argue that a predominant quality to be expected in a successful gene is ruthless selfishness. This gene selfishness will usually give rise to selfishness in individual behavior. However, as we shall see, there are special circumstances in which a gene can achieve its own selfish goals best by fostering a limited form of altruism at the level of individual animals. 'Special' and 'limited' are important words in the last sentence. Much as we might wish to believe otherwise, universal love and the welfare of the species as a whole are concepts that simply do not make evolutionary sense. " The Selfish Gene. 1976.

Coming in the late 1970s the conception of The Selfish Gene coincides with the rise of the new political and economic ideologies of the Right: the new libertarianism, that deprecates government's role in society and says it's every man for himself. Neolibertarians distrust government and believe an abstraction called "the market" can mediate and arbitrate the price of everything (including political and white-collar corruption). This is erroneously called Neoliberalism, but there is nothing liberal about it. Three years later Margaret Thatcher was elected as Prime Minister of the UK and began transforming society with this same metaphor in mind. Stripping away anything which put the breaks on the profit making activities of business people or the need for them to contribute to society beyond paying the lowest possible wages to their staff. Her successors, including the New Labour Party, have gone much further: NLP removed credit controls allowing the largest amount of private debt in recorded history to build up (topping 500% of GDP in the UK ca. 2008) so that when bust inevitably followed boom, it was arguably the worst in recorded history. The present government are slowly dismantling the welfare state by selling off provision of services to the private sector where they themselves are major investors (in any sane society this would count as corruption). Meanwhile vast amounts of taxes go unpaid, and the wealthy are helped with the process of insulating themselves from social responsibility by shoddy laws enacted by their peers in government and corrupt administrators.

Dawkins and Darwin must be seen in their political landscape. Must be seen as active participants in both shaping and justifying the ideology of the ruling classes, at least in Britain. Seeing things clearly is part of waking up.

Each year we discover more and more about the role of symbiosis in speciation, in the effective working of our gut, in evolution generally. And not just symbiosis, but cooperation more generally, and related events like hybridisation. All of these make a mockery of the Selfish Gene metaphor because everywhere we look things only work at all when they work together. Where Dawkins saw altruism as rare, it is in fact ubiquitous. Where Dawkins saw genes only working for the benefit of similar genes, in symbiogensis and symbiosis completely unrelated genes benefit each other. Genes are in fact very generous.

Dawkins and Darwin must be seen in their political landscape. Must be seen as active participants in both shaping and justifying the ideology of the ruling classes, at least in Britain. Seeing things clearly is part of waking up.

Each year we discover more and more about the role of symbiosis in speciation, in the effective working of our gut, in evolution generally. And not just symbiosis, but cooperation more generally, and related events like hybridisation. All of these make a mockery of the Selfish Gene metaphor because everywhere we look things only work at all when they work together. Where Dawkins saw altruism as rare, it is in fact ubiquitous. Where Dawkins saw genes only working for the benefit of similar genes, in symbiogensis and symbiosis completely unrelated genes benefit each other. Genes are in fact very generous.

In fact there's no level of organisation in which the part can function independently from the whole. A gene requires a genome; a genome requires a population; a population requires an ecosystem. The dependency is not mere abstraction, it's an absolute. For example, the cell is a product of its genome as a whole (including epigenetic factors) and without the cell the gene can neither survive nor function. This is not to say that there is no competition or no examples of self-interested behaviour. But it is to question the pivotal role given to metaphors involving selfish individuals pursuing self-interested goals benefiting the whole, especially when generally speaking. It is to question what is a self in the first place. When what we think of as a "self" is in fact a community, what does selfish even mean?

The Values of Modernist Buddhism

The self-justificatory Victorian metaphor runs very deep in British society. And is generally quite popular at the moment, because the USA is inventing stories to justify its position in the world: the self-declared champion of freedom. The idea that the vision of nature put forward by ideological zealots, steeped in the politics of Libertarianism, is the only possible view is beyond a joke. It's a tragedy. At present it is being used to justify exploiting working people throughout the first world to pay off debts incurred by corrupt bankers and their political facilitators. The effect in the developing world is often akin to slavery. The every-man-for-himself and no-holds-barred approach was supposed to allow wealth to accumulate across the society, through "trickle down economics", but in fact it just meant that the rich got richer and the poor got poorer. Wealth is being funnelled up to the wealthy. This happens because given free reign, greed forces wage-earners to work longer for less money. Neolibertarians only see staff as an expense that sucks money out of the pockets of shareholders: a line item to be minimised. People don't matter to them.

More than any other area of science I know of, the science of evolution reflects politics and in particular the political values of the Right. As George Lakoff has wryly observed, the Right have not only been setting the political agenda for the last 4 or 5 decades, they have been cunningly using language to frame and control the political discourse for everyone. I fear we may be seeing an end to the liberal experiment, to the spirit of liberté, égalité, and fraternité.

This critique, if you believe it, has much wider implications. The idea of creating a world that might be consistent with Buddhist values is at present losing ground. Survival of the fittest, as envisaged by the wealthy elite, is driving us backwards. A survey of Buddhist countries offers no great insights and no models for emulation (unless we fancy the brainwashed peasantry of Bhutan). While I do not agree that Modern Buddhists are necessarily complicit in and facilitating this situation (Slavoj Žižek strikes me as a fatuous pseudo-intellectual), I am not seeing the clarity of economic and political thinking from Buddhist leaders that might make a difference. Because of this deficit I see Buddhists engaged in activities, which, while in themselves are admirable enough, are entirely ineffectual and insufficient to make a significant difference to the status quo. We continue to reach 100s of people each year in countries with populations of 10s or 100s of millions. Of those 100s the vast majority are middle-aged and middle class and none at all are of the ruling classes. Indeed as Westerners have begun to take Buddhism more seriously, the Western world has taken substantial steps away from our values because legislators and businessmen are now one and the same. That was the revolution. It was not televised. The rule of the business people, for the business people, by the business people. The only Buddhists challenging this at present are those taking mindfulness into the corporate and political arenas and they seem to get nothing but flack from other Buddhists.

At present our Buddhist leaders tend to be introspective and politically naive meditation teachers. Our organisations are headed by introverts who fail to be outward looking enough to properly engage in politics let alone effective organisational communication. We have great difficulty managing the politics of our own organisations, let alone getting engaged with the world in a united way.

Modern Buddhists generally have a tendency to disengage from worldly events and distance themselves from politics. We still draw heavily on the baby-boomer counter-culture ethos that sat back and let the Neolibertarians take over. In this we are quite unlike our monastic antecedents. Buddhist monks were sometimes so wealthy and so heavily involved in politics that they virtually ran empires. Sometimes the conflict between monks and bureaucrats spilled over into open war, in which the monks usually lost out. Obviously some kind of middle-way would be preferable.

We Buddhists need to get up to speed with economic and political critiques and to get involved in public discourse. We need to understand the metaphors that underpin modern life, where they originate, how pervasive they are, and develop strategies to effectively counter them where necessary. At present all the major political parties have bought into Neolibertarian ideology to some extent and it is inimical to our values. Dropping out of the system does not change the system. It merely allows the system to change in ways beyond our influence. This is the lesson of the baby-boomer counter-culture approach.

It won't be easy. Most of us are middle-class and middle-aged already (80% of the Triratna Order are over 40 and I gather this is not unusual in Buddhist Groups). We're used to being able to do pretty much what we want in exchange for our functionary roles in the economy. We don't expect to lose our freedom of religion or our comfortable way of life. Or we're comfortable with dropped-out obscurity. We do worry about being able to sustain that comfort after we stop working. And since we live longer, our retirement lasts longer and decrepitude progresses much further before we die, meaning we have to put more effort into ensuring that comfort. We're hardly revolutionaries, though many of us like to think we are. With all due respect to my teachers, the counter-culture thing was never revolutionary because it hardly changed anything and in contrast to the rise of Neolibertarianism that happened at the same time, it was negligible. Contrast this with the aggressive engagement and success of the suffrage movement and its successors (though I sometimes blanch under the scorn of feminists, I support equal rights). There are models for changing the social landscape, and to-date we are too proud to follow any of them.

I'm not a Buddhist leader, nor do I have the ear of any Buddhist leaders. I know one or two influential people read this blog, but I'm not getting open endorsements or anything. The best I can hope for is to be an irritant. One of my intellectual mentors once asked "Of what use to me is a friend who is not a constant source of irritation?" (Richard P Hayes. Land of No Buddha, p.179). I've tended to paraphrase his conclusion as "a friend ought to be a constant source of irritation; but not a source of constant irritation." I hope to be a friend to Buddhists everywhere.

This critique, if you believe it, has much wider implications. The idea of creating a world that might be consistent with Buddhist values is at present losing ground. Survival of the fittest, as envisaged by the wealthy elite, is driving us backwards. A survey of Buddhist countries offers no great insights and no models for emulation (unless we fancy the brainwashed peasantry of Bhutan). While I do not agree that Modern Buddhists are necessarily complicit in and facilitating this situation (Slavoj Žižek strikes me as a fatuous pseudo-intellectual), I am not seeing the clarity of economic and political thinking from Buddhist leaders that might make a difference. Because of this deficit I see Buddhists engaged in activities, which, while in themselves are admirable enough, are entirely ineffectual and insufficient to make a significant difference to the status quo. We continue to reach 100s of people each year in countries with populations of 10s or 100s of millions. Of those 100s the vast majority are middle-aged and middle class and none at all are of the ruling classes. Indeed as Westerners have begun to take Buddhism more seriously, the Western world has taken substantial steps away from our values because legislators and businessmen are now one and the same. That was the revolution. It was not televised. The rule of the business people, for the business people, by the business people. The only Buddhists challenging this at present are those taking mindfulness into the corporate and political arenas and they seem to get nothing but flack from other Buddhists.

At present our Buddhist leaders tend to be introspective and politically naive meditation teachers. Our organisations are headed by introverts who fail to be outward looking enough to properly engage in politics let alone effective organisational communication. We have great difficulty managing the politics of our own organisations, let alone getting engaged with the world in a united way.

Modern Buddhists generally have a tendency to disengage from worldly events and distance themselves from politics. We still draw heavily on the baby-boomer counter-culture ethos that sat back and let the Neolibertarians take over. In this we are quite unlike our monastic antecedents. Buddhist monks were sometimes so wealthy and so heavily involved in politics that they virtually ran empires. Sometimes the conflict between monks and bureaucrats spilled over into open war, in which the monks usually lost out. Obviously some kind of middle-way would be preferable.

We Buddhists need to get up to speed with economic and political critiques and to get involved in public discourse. We need to understand the metaphors that underpin modern life, where they originate, how pervasive they are, and develop strategies to effectively counter them where necessary. At present all the major political parties have bought into Neolibertarian ideology to some extent and it is inimical to our values. Dropping out of the system does not change the system. It merely allows the system to change in ways beyond our influence. This is the lesson of the baby-boomer counter-culture approach.

It won't be easy. Most of us are middle-class and middle-aged already (80% of the Triratna Order are over 40 and I gather this is not unusual in Buddhist Groups). We're used to being able to do pretty much what we want in exchange for our functionary roles in the economy. We don't expect to lose our freedom of religion or our comfortable way of life. Or we're comfortable with dropped-out obscurity. We do worry about being able to sustain that comfort after we stop working. And since we live longer, our retirement lasts longer and decrepitude progresses much further before we die, meaning we have to put more effort into ensuring that comfort. We're hardly revolutionaries, though many of us like to think we are. With all due respect to my teachers, the counter-culture thing was never revolutionary because it hardly changed anything and in contrast to the rise of Neolibertarianism that happened at the same time, it was negligible. Contrast this with the aggressive engagement and success of the suffrage movement and its successors (though I sometimes blanch under the scorn of feminists, I support equal rights). There are models for changing the social landscape, and to-date we are too proud to follow any of them.

I'm not a Buddhist leader, nor do I have the ear of any Buddhist leaders. I know one or two influential people read this blog, but I'm not getting open endorsements or anything. The best I can hope for is to be an irritant. One of my intellectual mentors once asked "Of what use to me is a friend who is not a constant source of irritation?" (Richard P Hayes. Land of No Buddha, p.179). I've tended to paraphrase his conclusion as "a friend ought to be a constant source of irritation; but not a source of constant irritation." I hope to be a friend to Buddhists everywhere.

~~oOo~~

It so happens that George Lakoff recently updated his book on political metaphors and framing political debates: Don’t Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate. Due in shops mid September 2014. Worth a read if this kind of thing floats your boat.