I've not been thinking much about the Dharma per se this week. Most of my reflection time has been spent mulling over Kukai's trip to China in 804-6. It's a fascinating episode in the life of one of my very favourite historical Buddhists - yes one of my Buddhist heros!

I've not been thinking much about the Dharma per se this week. Most of my reflection time has been spent mulling over Kukai's trip to China in 804-6. It's a fascinating episode in the life of one of my very favourite historical Buddhists - yes one of my Buddhist heros!Kukai had dropped out of mainstream life to practice as a freelance ascetic, which made him an outlaw in late 8th century Japan. Some years earlier he had written and circulated a satirical attack on the official confucianist doctines of the Imperial state. Having repudiated by word and deed the Imperial orthodoxy, he was the antithesis of an establishment figure.

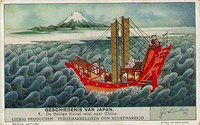

So how did he come to be included in the diplomatic mission to Tang China in 804? Maybe his relatives pulled some strings, but historians love to point out that his family and clan were Aristocracy in decline, and probably had little influence with the court. It may have been because he volunteered to go on a mission which most people in the right mind did anything they could to get out of. Trips to China involved taking completely unsuitable craft across over 1000km of open ocean, where more often than not they were sunk by storms. It wasn't certain death, but two of the four boats in the fleet were lost in the first week. Kukai had volunteered because he figured that someone in China would be able to explain the Mahāvairocana Sutra to him.

The fact is that we don't know how Kūkai got on the boat, nor the circumstances of his ordination as a bhikṣu. But we know that he caught the boat, survived the storm, and charmed the pants off the Chinese when he got there. Kūkai's boat was blown 1600km south of it's intended destination. The port authorities at the out of the way port refused them permission to land. They sailed north to the city of Fu-chou where their boat was impounded and the crew forced to live in a swamp for a few weeks. Until Kūkai wrote a letter to the authorities that so impressed them that I organised proper accommodation for the rest of the mission - including the official ambassador and his staff. Kūkai again prevailed upon the Chinese when he was at first not permitted to travel to Chang-an the capital. Finally, after a month of travelling overland, and the death of the Chinese Emperor just a few weeks after their arrival, Kūkai managed to get himself posted to Xi-ming temple.

Xi-ming was the greatest temple in China, and contained one of the great libraries in history. It housed for instance the texts brought back from India by Xuan-zang and other Chinese pilgrims. It was the nexus of Chinese efforts to translated Buddhist texts, and Buddhist culture into Chinese. At Xi-ming Kūkai learned Sanskrit, in the space of a few weeks, from an ex-pat Indian monk who had himself been trained at Nalanada. He also studied poetry and calligraphy, and is a celebrated exponent of both arts.

Chang-an at this time was the largest city in the world, with more than a million inhabitants. The regular, tree lined streets were wide, clean, ordered, and foreigners could be seen everywhere. The Silk Rd was still open and Chang-an formed one end of it. It was one of those times in Chinese history which was very open to outsiders and their cultures. These were prosperous times and Buddhist temples in particular prospered. The wealth of the dozens of temples has been described as "incalculable". Amongst the Buddhist temples were of course Taoist and Confucian temples, but also a couple of Nestorian Churches (which gave a Jesuits a fright centuries later!), Manichean and Zoroastrian temples, as well as, possibly a mosque or two.

Kūkai had grown up in rural Japan, and after only a couple of years in the very much smaller capital city Nara, had absconded back to the wilderness. Kūkai even described himself as a child of nature. So what would it have been like for him to arrive in uber-urban Chang-an? What would the impact of this most cosmopolitan of cities?

All we really know is that Kūkai made excellent use of his time in Chang-an. He arrived back in Japan two years later, eighteen years earlier than expected, with a boatload of new scriptures, images and artefacts, but also with a new language and script, and with a new form of Buddhism. It would take almost the rest of his life, three decades, to firmly establish Shingon. But while Shingon waxed and waned in terms of influence on Japanese society, the thing that really revolutionised it was the idea of writing in a syllabic script. Until then all writing was in Chinese characters and most in the Chinese language and only the male aristocracy were suffered to learn Chinese. It is ironic that the most valuable thing that Kūkai brought back from China had been a way for the Japanese to free themselves of the Chinese cultural hegemony!