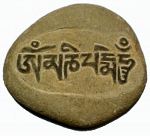

In my last essay on this all important mantra I summarised the findings of Alexander Studholme on the origins of the oṃ maṇipadme hūṃ mantra, and some interesting facets of the identity of Avalokiteśvara in the Karandavyuha Sutra.

In my last essay on this all important mantra I summarised the findings of Alexander Studholme on the origins of the oṃ maṇipadme hūṃ mantra, and some interesting facets of the identity of Avalokiteśvara in the Karandavyuha Sutra.One of the main questions that Westerners ask when they come across something like a mantra is "what does it mean?" Donald Lopez, in Prisoners of Shangrila, outlines the progress of the Western understanding of the meaning of oṃ maṇipadme hūm over the centuries. One feature of the Western commentaries on the mantra is that the Westerners are convinced that the Tibetans do not know the meaning of the mantra. This is an example of what Edward Said called "Orientalism" - an attitude of disdain towards Asians who did not conform to European norms, and assessments of Asian culture from those norms. Eurocentrism certainly comes across as arrogant and over-bearing in relation to oṃ maṇipadme hūṃ.

The first European interpretation of the mantra dates from 13th century when William of Rubruck reported that the Tibetans chanted "om mani baccam" which is "God, thou knowest". Over the years such basic mis-hearings, and mis-interpretations were the rule. Interpretations such as "Lord forgive my sins", "O god Manipe, save us" followed. In the 18th century the Jesuit Ippolito Desideri who actually learned Tibetan published his interpretation of the mantra as "O thou who holdest a jewel in Thy right hand, and art seated on the flower Pêmà", which may just capture one of the senses of manipadme . However with the coming of scientific philology, in part inspired by the discovery of the Sanskrit Grammarians, a new interpretation emerged. In 1831 Heinrich Julius von Klaproth explained that padmè was padma in the locative case (i.e. in the lotus) and that the mantra means: Oh! The jewel is in the lotus, Amen. From this time on some variation on "The Jewel in the Lotus" became the standard meaning of the mantra. [1] Of course oṃ and hūṃ are always difficult since they are not words in the way that maṇi and padma are, and so they are treated differently, but maṇi and padma become standardised in English language works as two words with padme in the locative case.

The apotheosis of this, orientalist, interpretation is perhaps represented by Lama Govinda's book "The Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism", in which the mantra is explicated over the course of 300 pages. Lopez notes that despite its title it is "based on no Tibetan text", but draws on "the Upanishads, Swami Vivekananda, Arthur Avalon, Alexandra David-Neel, and especially the tetralogy of Evans Wentz". "Lama Anagarika Govinda" always brings to mind Harold Bloom's quip about Freudian Literacy Criticism being like the Holy Roman Empire - not Holy, not Roman, and not an Empire. Perhaps it would equally apply to "Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism". Even Robert Thurman a scholar/practitioner in the Gelug tradition adopts "The Jewel in the Lotus" as the explanation of the mantra in his book Essential Tibetan Buddhism. As Lopez notes, no Tibetan text is ever cited to justify this reading.

As early as the 1950's David Snellgrove pointed out that maṇipadme is not two words but a single compound. Maṇi is uninflected, and maṇipadme is not the locative, but a vocative of the feminine form maṇipadmā. The compound is according to Sten Konow (quoted by Lopez) a bahuvrīhi compound which means "O Jewel-lotus" Alexander Studholm critiques this gloss, and by referring to a number of similar expression in Mahāyāna literature concludes:

"The expression should be parsed as a tatpurusa, or "determinative," compound in the (masculine or neuter) locative case, meaning "in the jewel-lotus," referring to the manner in which buddhas and bodhisattvas are said to be seated in these marvellous blooms and, in particular, to the manner in which more mundane beings are believed to appear in the pure land of the buddhas". [2]This I think sorts out the grammatical issues, although without reference to traditional Tibetan exegesis. Ironically, given the effort that has gone into answering it, Western scholars and Buddhists may have been asking the wrong question. Faced with a mantra the tradition doesn't ask "what does it mean?" it asks "what does it do?". The mantra in the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra is said to result in rebirth in one of the hair pores on Avalokiteśvara's body. This alternate destination to the usual pure land, is probably influenced by Puranic traditions, but has the same advantages as a pure land. The Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra likens chanting the mantra to a pre-existing tradition of calling to mind of the name of a Buddha or Bodhisattva (nāmanusmṛti). That is to say that the mantra is an invocation of the deity, and offers similar protection to that offered in the Saddharmapuṇḍarika, to the one who calls out the name of Avalokiteśvara.

A much more important approach to "meaning" in esoteric traditions is to take the individual syllables one at a time and establish connections with other sets of six such as the six realms. Avalokiteśvara appears in each of the realms to save the beings there from the particular kinds of suffering that afflict beings in them. When they do address the semantic meaning of maṇipadme, it seems that Tibetan texts read it as jewel-lotus. This fact may have been of very little importance in Tibet however, as the mantra is a invocation of Avalokiteśvara, and what else does one need to know?

However this is not to say that the "jewel in the lotus" interpretation is wrong. It is a powerful image, completely consonant with Buddhist principles, and has inspired many people over the years. It may be a case for Sangharakshita's expressed preference for bad philology with good doctrine being preferable to good philology and bad doctrine. It is bad philology, but since the function of the mantra is more important than it's "meaning" the semantics are actually of only minor interest.

Another way of understanding what the mantra does, and which may help us to understand how the chanting of sounds, the semantic content of which may be completely obscure for the person chanting them comes from Ariel Glucklick's phenomenological study of Tantric magic. Magic, he says:

"is based on a unique type of consciousness: the awareness of the interrelatedness of all things in the world by means of simple but refined sense perception… [magical actions, such as mantra chanting] constitute a direct, ritual way of restoring the experience of relatedness where that experience has been broken" [3]The idea here is not that the mantra affects anything in the outside world - the distinction of inside/outside has no ultimate meaning in Buddhist epistemology in any case - it addresses the sense of relatedness. In the case of illness this awareness is itself healing. In the case of the incessantly chanted mantra is maintains the empathetic link with all beings, and no doubt produces a sense of wholeness and well-being. There is nothing overtly mystical in this explanation as Glucklich adds. "It is a natural phenomenon, the product of our evolution as a human species and an acquired ability for adapting to various ecological and social environments".[4] This is no to deny benefits which go beyond the understanding of science and scholarship. But here at least is an explanation which allows the materialistic Western the leeway they might need to unselfconsciously engage in mantra chanting without worrying about metaphysics. Mantra works on any number of levels, some of which are undoubtedly comprehensible to the modern Western intellect.

Notes.

- Lopez, D. S. (jr.) 1988. Prisoners of Shangri-la : Tibetan Buddhism and the West. Chicago University Press. p.114ff.

- Studholme, Alexander. 2002. The origins of oṃ maṇipadme hūm : a study of the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra. Albany : State university of New York Press. p.116

- Glucklich, Ariel. 1997. The End of Magic. New York : Oxford University Press. p.12

- Ibid., p.12.

For the oṃ maṇipadme hūṃ mantra in a variety of scripts see the Avalokiteśvara Mantra on visiblemantra.org.

image from: He's the Wiz!