na hi verena verāni, sammantīdha kudācanaṃVerse 5 is one of the most famous Buddhist aphorisms. Hatred is like fuel on the fire, it only leads to more hatred. These two verse continue the theme established in verses 3 and 4: that we are never justified in holding a grudge. Vera, translated here as hatred can also mean "revenge, hostile action." It's actually related to the term vīra which usually translates as "hero" but can also mean something like "mighty". Avera then is the absence of hatred: "friendliness, friendly, peaceable".

averena ca sammanti, esa dhammo sanantano

pere ca na vijānanti, mayamettha yamāmase

ye ca tattha tato sammanti medhagā

Not by hatred are hatreds calmed at any time

By non-hatred they cease, this teaching is primeval

And others don't realise that we should be restrained.

But if they do realise this, then they will settle quarrels.

The verses tell us that this idea is sanantano or "primeval, or "of old, for ever, eternal", the word being related to the Latin senex, and the English senile. So it could mean that the teaching is old, or that it will always apply.

Either way it is an important principle. And those who know this principle restrain their hatred (line 6a). Actually the first line of verse 6 is difficult to translate because the word yamāmase seems only to occur once (a hapax legomenon), and is of unclear etymology. I have followed K.R. Norman in reading it as an optative of √yam a verbal root meaning 'restraint'. Others relate it to the god of death Yama, and make the line say something like: Others do not know that we must all face death. There is good and useful Dharma in this approach. It reminds us that our future destination depends on our conduct in this life. If we indulge in hatred the traditions suggests that we are destined for the hell-realms. I would say that being angry has a hellish quality anyway. [see also Jayarava Rave. 08-02-2008: The Anger Eating Yakkha] That said however, the idea of restraint seems to fit the context a little better I think.

Although it is clear that the text is saying not to hold grudges, and that when one feels anger one should restrain oneself, it's not entirely clear how one might do that from these verses. There is such a plan in the Aṅguttara Nikāya however (sutta V.161). Here we find five methods for dealing with grudges:

- Practice the brahma-vihāra meditations. If you feel hatred towards someone then try to cultivate the opposite: ie love, compassion, equanimity. (the text suggests mettā, karuṇā, and upekkhā but leaves out muditā and so counts this as three methods). We could call this 'cultivating the opposite'.

- Pay the person no attention, give no thought to them. This is sometimes called the "blue sky mind" approach - don't feed the feelings and they will subside.

- Reflect on the consequences. Particularly reflect that whatever bad thing that person has done to you, they will have to experience the fruit of that action which will be painful for them!

A more active form of the blue sky approach which I find quite useful is to think about something else. Many of my raves for this blog have resulted from me taking up a subject to reflect on precisely to stop my attention wandering onto less helpful subjects.

Reflecting on the consequences is also, effectively, reflecting on the Dharma. This is inherently positive. In Dhammapada 3-4 we saw that hatred is never a good thing - that the effects on us of entertaining anger are always negative. So reflect on the consequences of that person shouting at you, or bashing you. As I noted last week, our culture is one in which we seek to punish (ie inflict harm upon) anyone who breaks the law. But since some one who abuses us will suffer anyway, is there really a need to inflict more suffering on them. The question is: "would seeing another person suffer make us happy?" If we see that other person as a human being, then we will not feel joy at their suffering. We know what suffering feels like. We know how unbearable it can be. We know that if we inflict pain because we are angry, that person will become angry and inflict pain also. This has to stop. We must try to stop the cycle of anger and harming. Really reflecting on the causes and consequences of anger and hatred is quite sobering. If we reflect on what might have led a person to want to harm us, we will find fear and anger at the root of it. If we wonder why are they experiencing fear and anger, then we will see that they too have been victims of other people's fear and anger. They have learned this wrong lesson that we seem to teach everyone - that despite what we may say, anger and lashing out are legitimate responses some times.

I recall in Michael Moore's film, Bowling for Columbine, Mike was interviewing a PR man at Lockheed-Martin the massive weapons manufacturing business. They were standing in front of a very large missile, one that could only be used to strike at many people a very long way away (i.e. a weapon of mass destruction). He held his arms wide and his hands open, in the classic gesture of honesty, and said that he did not understand why these boys, who had gunned down many of their school mates, would resort to violence to resolve their problems. Why indeed? A very large missile, designed to deliver weapons of mass destruction is just the result of coordinated hatred, and of course our leaders do often resort to violence to solve their problems with the help of weapons manufacturers like Lockheed-Martin. And we often allow the emotions like hatred to persist in our minds. Of course we might take our revenge by something as simple as withdrawing our affection, or by doing something we know to be annoying. We might not be using a missile to kill thousands of people, or a handgun to kill our classmates. But it is only the scale that is different. If we were angry enough, and someone put a gun in our hand... well sometimes perhaps it doesn't pay to dwell on the consequences for too long. Just enough get the message and move on.

There is a definite sense in these early texts of working to eliminate negative or harmful mental states. There is none of the psycho-babble about allowing your anger to have expression or find an outlet. This is because from the Buddhist point of view the angry thought harms you, and any action undertaken with anger in mind will cause harm (viz my post on Dhammapada 1 - 2). Hatred is harmful so do what you can, whatever you have to, in order for it to subside. There is also no sense in early Buddhist texts of just thinking of anger as 'energy' as some Tantric traditions might do. Sure, there is energy: but are we alert enough, aware enough, Awake enough to refrain from hurting when we are angry? Not in most cases I think. Not without a great deal of training, and a great deal of mettā. Better to err on the side of caution with anger. It can be insidious. We can find ourselves justifying little cruelties to ourselves and others on the basis that "it's just energy", or "it's for their own good". Better to just nip it in the bud.

Bearing grudges only makes you miserable, and you are probably holding onto the possibility of harming someone in return for the harm they caused you. Hatred is never pacified by hatred - it never has been and it never will be. It is only by the opposite, by avera - non-hatred, that hatred is pacified. The good news is that by not bearing grudges, by not holding out for revenge, the hate will subside in you. When hate subsides it makes room for other more positive emotions. Dwelling in mettā all the time is equated with nibbāna in many texts.

See also my commentary on Dhammapada v.1-2, and v.3-4

Sue Hamilton's book

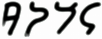

Sue Hamilton's book  The first script to be used for writing Indian languages was Kharoṣṭhī beginning in the 3rd or 4th century BCE. It was used for several hundred years to write the local dialects, but also Sanskrit. Kharoṣṭhī was used in Gāndhāra in North West India (what is now the Pakistan shading into Afghanistan - i.e. Taliban country) and in central Asia. It shares many features with the Aramaic used by Persian administrators at the time when they were influential in that region, and most scholars accept that Aramaic was probably the model for Kharoṣṭhī. It was both carved in rock and written with pen and ink on birch bark. Quite a number of early Buddhist texts survive in Sanskrit and in the Gāndhārī Prakrit (roughly the vernacular dialect of Gāndhāra). A Gāndhārī version of the Dhammapada survives for instance, and several other texts which parallel the Pāli but with interesting mostly minor differences. These texts have helped to flesh out our knowledge of the different early schools of Buddhism.

The first script to be used for writing Indian languages was Kharoṣṭhī beginning in the 3rd or 4th century BCE. It was used for several hundred years to write the local dialects, but also Sanskrit. Kharoṣṭhī was used in Gāndhāra in North West India (what is now the Pakistan shading into Afghanistan - i.e. Taliban country) and in central Asia. It shares many features with the Aramaic used by Persian administrators at the time when they were influential in that region, and most scholars accept that Aramaic was probably the model for Kharoṣṭhī. It was both carved in rock and written with pen and ink on birch bark. Quite a number of early Buddhist texts survive in Sanskrit and in the Gāndhārī Prakrit (roughly the vernacular dialect of Gāndhāra). A Gāndhārī version of the Dhammapada survives for instance, and several other texts which parallel the Pāli but with interesting mostly minor differences. These texts have helped to flesh out our knowledge of the different early schools of Buddhism. Brahmī was the first truly indigenous Indian script. The name means simply "God" - Brahmā having been adopted as a creator god by this point. It was a definite improvement on Kharoṣṭhī in having individual signs for initial vowels, and greater variation between characters which made it more readable. My guess however is that it was designed for carving rather than writing per se. The signs are simple, geometric and quite linear. Aśoka (mid to late 3rd century BCE) used this script for most of his rock edicts - a few were in Kharoṣṭhī or Aramaic, and one was in Greek reflecting the local usage in the far West of his imperium. Probably most Buddhist texts were written in this script in Eastern and Central India until the 3rd century CE.

Brahmī was the first truly indigenous Indian script. The name means simply "God" - Brahmā having been adopted as a creator god by this point. It was a definite improvement on Kharoṣṭhī in having individual signs for initial vowels, and greater variation between characters which made it more readable. My guess however is that it was designed for carving rather than writing per se. The signs are simple, geometric and quite linear. Aśoka (mid to late 3rd century BCE) used this script for most of his rock edicts - a few were in Kharoṣṭhī or Aramaic, and one was in Greek reflecting the local usage in the far West of his imperium. Probably most Buddhist texts were written in this script in Eastern and Central India until the 3rd century CE.

Two other scripts which are frequently used in Buddhist contexts are the closely related Lantsa and Ranjana, from Tibet and Nepal respectively. These are often assumed to be identical but this is not true. They emerged in about the 11th century and are both are still in use for ceremonial or decorative purposes. Tibetan texts will often have the Sanskrit title in Lantsa as well as dbu-can at their head.

Two other scripts which are frequently used in Buddhist contexts are the closely related Lantsa and Ranjana, from Tibet and Nepal respectively. These are often assumed to be identical but this is not true. They emerged in about the 11th century and are both are still in use for ceremonial or decorative purposes. Tibetan texts will often have the Sanskrit title in Lantsa as well as dbu-can at their head.