Over the past year or so I have been reflecting quite a bit on the Internet as a medium of communication and more recently have been pondering the phrase "virtual reality" and it's derivatives. I'm not sure when I first heard this term, but I recall reading William Gibson's Neuromancer in 1991. It was on the reading list for my post graduate librarianship course at Victoria University, NZ. I think it was recommended by Alastair Smith who I see is still on the staff there. Gibson played a big part in helping us to visualise what a virtual reality might look like, kind of like Arthur C. Clarke and satellites.

Over the past year or so I have been reflecting quite a bit on the Internet as a medium of communication and more recently have been pondering the phrase "virtual reality" and it's derivatives. I'm not sure when I first heard this term, but I recall reading William Gibson's Neuromancer in 1991. It was on the reading list for my post graduate librarianship course at Victoria University, NZ. I think it was recommended by Alastair Smith who I see is still on the staff there. Gibson played a big part in helping us to visualise what a virtual reality might look like, kind of like Arthur C. Clarke and satellites.Virtual is an interesting word. It has been traced back to an Indo-European root *viltro meaning "freeman" (reconstructed roots are prefixed with an asterisk in linguistic circles). This manifests in Sanskrit and Avestan as the word vīra: "manly, mighty, heroic". And in the Buddhist technical term virya: "vigour, energy, effort, exertion". It comes into English via the Latin word vir: "man, hero". Along one branch it gives us the word "virtue" via the Old French vertu. And by another route we get "virtual" via Latin virtus, Medieveal Latin virtuosus, Middle English virtualis.

According to the Concise Oxford English Dictionary "virtual" means:

adj. 1 that is such for practical purposes though not in name or according to strict definition. 2 Optics. relating to the points at which rays would meet if produced backwards. 3. Mech. relating to an infinitesimal displacement of a point in a system. 4. Computing. not physically existing as such but made by software to appear to do so.Reality is of course a very difficult thing to define especially if we are using a Buddhist frame of reference. I'll leave it a bit vague for now. It seems to me that two meanings of the term "virtual reality" are intended. The first is that it is a computing term and suggests a reality which is not physical but is made to appear so. The second is more implied which is that virtual reality is a reality that is like reality for practical purposes.

Virtual reality is technically limited to total immersion environments that are designed to stimulate more than one sense simultaneously - usually sight, sound, and touch as a minimum - and give the sense of being in another reality, or something that is like a reality for practical purposes. These attempts to create a sense of being in a different reality are successful to some extent. However with the growth of the world wide web the idea of virtual reality is being applied to more and more situations. In particular I am interested in the notions of virtual community, and more specifically virtual sangha.

A virtual community is ostensibly a community which does not exist physically, but which is like a community for practical purposes. The connections between people are electronic often with an emphasis on plain text forms of communication. "Community" previously refer to a group of people who lived in close proximity and were connected through a variety of personal relationships. In the modern west this idea of community began to break down during the industrial revolution when communities were broken up by people moving away to cities for work. In the present a minority of people still live where they grew up and have maintained the relationships of their early life. We frequently live amongst strangers, don't know or speak to our neighbours, and live a days travel or more from our family. Families themselves used to encompass many layers of relatives, but increasingly have become nuclear - parents and children living in relative isolation. And of course nowadays many parents find living together intolerable and split up. Increasingly people are becoming isolated and cut off from each other - the basic unit of society is the individual. This is still not entirely true in more traditional societies. It's clear from talking to Indian friends for instance that the family is still the basic unit of society there. Community is also used in the sense of people with, for example, a common demographic (the Black community in the UK), or interest (the sporting community). The idea here being that relationships based on something other than geographical proximity constitute a community.

The idea of a virtual community can be seen as a response to the breakdown of actual community. Marshall McLuhan's famous statement that "the medium is the message" is meant to suggest that what humans value is a sense of connection and that electronic media represent a manifestation of this desire. By providing a series of electronic communication channels linking people they are provided with a sense of being a member of a community. I argued this in 2005 with respect to cell phones for instance: one's cellphone contacts are one's community. Social networking sites such as MySpace and Facebook tap into the same desire to feel connected (incidentally I've abandoned using MySpace due to inappropriate ads appearing on my page).

Online forums and bulletin-boards and such like are another manifestation of this. These allow disparate people to exchange public text based messages. There is a peculiar feature of online forums, even or perhaps especially Buddhist forums: they frequently descend into acrimony and bickering. Why they do this is still a moot point, but after 12 years or more of participating I've found the pattern repeats itself. Despite the obvious potential of these media they appear to bring out the worst in many people. My thinking on this is that computer mediated communication is inherently unsatisfying, especially in comparison to face to face communication. And in computing terms I think the problem is partly to do with bandwidth, and partly to the relationship we have with writing.

Bandwidth is a term which is used to refer to the capacity of a channel to carry information - it originated in radio I believe. Plain text is a very narrow medium. For instance let's say that my Facebook friend changes there main image and I write "I like your new haircut". If I am talking to a person face to face I can make these same words for instance a compliment or an insult with a flick of my eyebrows, or an inflection in my voice. I can imply many things through tone of voice, timing, facial expression, and body language while using an identical phrase. This suggests that words are less important than we usually think in communication.

The second point is that spoken language is a natural thing for most of us. Most humans learn to speak their mother toungue with almost no effort. We learn language naturally. A man of my acquaintance has deaf parents and his first language is sign-language! Writing however does not come naturally. Learning to write is difficult and laborious. Expressing ourselves in writing is not natural, and so there is a much wider range of ability than with spoken language. In fact I'd say that most people are not that good at written communication, even when they are good at oral communication. It's not that there is no skill in oratory, but that it is more natural and therefore we all acquire some skill in it.

So here we have a medium with limited expressive possibilities and which most people actually find unnatural to some extent. This is not a good starting point. And in fact I think what happens when we try to rely on internet as a substitute for face to face communication we start to feel a sense of alienation. I suspect that this is why forums are often fractious. I'm extremely doubtful as to whether the current generation of internet can provide any real sense of community. Such a community is ersatz at best. It cannot satisfy the longing for a sense of connection and belonging. This is because relationships can't be built on words.

There are some benefits to the medium. The ubiquity of internet access amongst my existing friends has meant that it is easier to keep in touch with them. It makes it easier to publish my thoughts - although this is a two edged sword as the bandwidth is now flooded with trivia and pornography making information more difficult to find. I have one or two relationships which are purely online which approximate something like friendship, but on the whole without the personal contact the relationships don't provide much in the way of satisfaction.

So I'm not very enthusiastic about the possibilities of virtual communities or even virtual sanghas as a substitute for the real thing. There is no substitute for personal contact. I would argue that virtual community is not like community for practical purposes: "virtual community" is an oxymoron. There's nothing like the real thing...

___________________

29 Sept 2010

See also this article by Malcom Gladwell: Small Change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted.

image: cover of Cybersociology Magazine : issue 2, 1997.

The average Buddhist reader has a naive approach to Buddhist texts. At worst we take them at face value as being what the texts themselves say they are: the actual words of the Buddha. At best we are slightly suspicious about translations, and might compare more than one when studying a text.

The average Buddhist reader has a naive approach to Buddhist texts. At worst we take them at face value as being what the texts themselves say they are: the actual words of the Buddha. At best we are slightly suspicious about translations, and might compare more than one when studying a text. Sue Hamilton's book

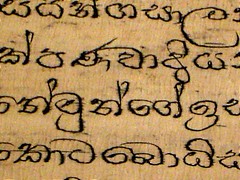

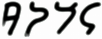

Sue Hamilton's book  The first script to be used for writing Indian languages was Kharoṣṭhī beginning in the 3rd or 4th century BCE. It was used for several hundred years to write the local dialects, but also Sanskrit. Kharoṣṭhī was used in Gāndhāra in North West India (what is now the Pakistan shading into Afghanistan - i.e. Taliban country) and in central Asia. It shares many features with the Aramaic used by Persian administrators at the time when they were influential in that region, and most scholars accept that Aramaic was probably the model for Kharoṣṭhī. It was both carved in rock and written with pen and ink on birch bark. Quite a number of early Buddhist texts survive in Sanskrit and in the Gāndhārī Prakrit (roughly the vernacular dialect of Gāndhāra). A Gāndhārī version of the Dhammapada survives for instance, and several other texts which parallel the Pāli but with interesting mostly minor differences. These texts have helped to flesh out our knowledge of the different early schools of Buddhism.

The first script to be used for writing Indian languages was Kharoṣṭhī beginning in the 3rd or 4th century BCE. It was used for several hundred years to write the local dialects, but also Sanskrit. Kharoṣṭhī was used in Gāndhāra in North West India (what is now the Pakistan shading into Afghanistan - i.e. Taliban country) and in central Asia. It shares many features with the Aramaic used by Persian administrators at the time when they were influential in that region, and most scholars accept that Aramaic was probably the model for Kharoṣṭhī. It was both carved in rock and written with pen and ink on birch bark. Quite a number of early Buddhist texts survive in Sanskrit and in the Gāndhārī Prakrit (roughly the vernacular dialect of Gāndhāra). A Gāndhārī version of the Dhammapada survives for instance, and several other texts which parallel the Pāli but with interesting mostly minor differences. These texts have helped to flesh out our knowledge of the different early schools of Buddhism. Brahmī was the first truly indigenous Indian script. The name means simply "God" - Brahmā having been adopted as a creator god by this point. It was a definite improvement on Kharoṣṭhī in having individual signs for initial vowels, and greater variation between characters which made it more readable. My guess however is that it was designed for carving rather than writing per se. The signs are simple, geometric and quite linear. Aśoka (mid to late 3rd century BCE) used this script for most of his rock edicts - a few were in Kharoṣṭhī or Aramaic, and one was in Greek reflecting the local usage in the far West of his imperium. Probably most Buddhist texts were written in this script in Eastern and Central India until the 3rd century CE.

Brahmī was the first truly indigenous Indian script. The name means simply "God" - Brahmā having been adopted as a creator god by this point. It was a definite improvement on Kharoṣṭhī in having individual signs for initial vowels, and greater variation between characters which made it more readable. My guess however is that it was designed for carving rather than writing per se. The signs are simple, geometric and quite linear. Aśoka (mid to late 3rd century BCE) used this script for most of his rock edicts - a few were in Kharoṣṭhī or Aramaic, and one was in Greek reflecting the local usage in the far West of his imperium. Probably most Buddhist texts were written in this script in Eastern and Central India until the 3rd century CE.

Two other scripts which are frequently used in Buddhist contexts are the closely related Lantsa and Ranjana, from Tibet and Nepal respectively. These are often assumed to be identical but this is not true. They emerged in about the 11th century and are both are still in use for ceremonial or decorative purposes. Tibetan texts will often have the Sanskrit title in Lantsa as well as dbu-can at their head.

Two other scripts which are frequently used in Buddhist contexts are the closely related Lantsa and Ranjana, from Tibet and Nepal respectively. These are often assumed to be identical but this is not true. They emerged in about the 11th century and are both are still in use for ceremonial or decorative purposes. Tibetan texts will often have the Sanskrit title in Lantsa as well as dbu-can at their head.