Attwood, Jayarava. (2013) Translation Strategies for the Cūḷa-Māluṅkya Sutta and its Chinese Counterparts. Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, 5, 42-63. Online: http://jocbs.org/index.php/jocbs/article/view/54/86

~o~

Revised 7.6.2012 with suggestions from Bryan Levman (BL). Many thanks.

Revised 7.6.2012 with suggestions from Bryan Levman (BL). Many thanks.I'VE BEEN READING the Cūḷa-Māluṅkya Sutta (M 63) which is a well known text, if only because of the allegory of the man shot by an arrow who refuses treatment before finding out all the details of the person who shot him, and what he was shot with, and dies because of the delay.

Perhaps we should not be surprised that translators and commentators have focussed on the main point, and glossed over the details that consumed the proverbial victim. Unfortunately some of the details are no longer understood because scholars, from Buddhaghosa onwards, were not paying attention. This makes for unconvincing translations. Having the kind of mind I do, I've been trying to reconstruct what the terms might have meant in order to accurately translate them. Some aspects are probably lost forever now. And before anyone gives me a hard time about becoming engrossed in the details; yes, I do see the irony; and no, I don't care. Since the Chinese version of the text (Taisho T.01 n.94 p.0917c21) provided an insight or two I have included my notes on it below as well. Thanks to Bryan Levman of the Yahoo Pāli Group for the suggestion of checking the Chinese, and supplying a reference to it. [Note: there are in fact two versions of this text in Chinese T 1.26 and T 1.94. Also it is paraphrased at T 1509.15]

Text

Here's my translation of the Pāli passage (M i.429)"Suppose a man was struck by an arrow thickly smeared with poison. His friends, colleagues and relations would engage an arrow-removing physician to treat him. And suppose the man would say: 'as long as I do not know that man who shot the arrow, whether he was warrior, priest, merchant, or peasant; his name & clan; whether he is tall, short, or middling; dark, brown or fair [of complexion]; and whether he came from a village, town or city I will not allow the arrow to be removed. And as long as I do not know whether I was shot with a cāpa bow or a kodaṇḍa bow; whether the bowstring was akka, or bamboo, or sinew, or bow-string hemp; whether the arrow shaft was gathered or planted; whether the arrow was fletched with the feathers of a vulture, heron, falcon, peacock, or sithilahanu; and bound with cow, buffalo, deer or monkey sinew; and whether the tip was a point, knife-edged, barbed, iron, calf-tooth, or leaf shaped, I will not allow the arrow to be removed.' That man would die before all this was known, Māluṅkyaputta."

The first thing that I was struck by is that the man's friends and relations ...bhisakkaṃ sallakattaṃ upaṭṭhapeyyuṃ. Ñāṇamoli & Bodhi (hence forth Ñ&B) render this as "brought a surgeon to treat him" (p.534) which as far as I can see leaves out the word sallakattaṃ altogether; c.f. Gethin (2008) "summon a doctor to see the arrow" which acknowledges the salla part of sallakattaṃ, but there is no verb 'to see' here! A doctor is bhisakka. The verb is upaṭṭhapeti a causative form of upaṭṭhahti 'to stand near, to attend, nurse'; from upa- 'near' + √sthā 'stand'; and it's in the optative mood so means 'would cause to attend'. So his relations 'would cause a doctor to attend' but again this misses out sallakattaṃ.

What does sallakattaṃ mean? The salla part means 'arrow' (which is what the whole thing is about) and this leaves us with -katta. According to BL "the only phonological explanation for the -tt- is if the geminate replaced an original conjunct consonant. The only one that would be contextually relevant is the noun karta [from √kṛt 'to cut'] which means "hole, cavity." Hence sallakatta must refer to the 'arrow wound'. This reading requires the verb to take two patients, and it's not clear whether this is allowed. DOP lists no examples of this.

BL notes that Buddhadatta concise Pāli-Eglish Dictionary defines sallakata as 'surgeon' (and sallakattiya as 'surgery', on the basis, apparently that salla can mean a surgical instrument. PED derives katta from *kartṛ 'worker' (the word exists in Skt. so I'm not sure why they use the asterisk). However the obvious meaning of sallakartṛ would be 'arrow maker' or 'fletcher', rather than surgeon. Compare MW śalyakartṛ 'arrow maker'; but śalyakarttṛ 'a remover of splinters, i.e. a surgeon'. Apte's English Sanskrit Dictionary suggests śalyataṃtravid and śasravaidyaḥ for surgeon. I think the answer is that Pāli sallakatta is Skt. śalyakarttṛ 'arrow remover' rather than śalyakartṛ 'arrow maker' or śalyakarta 'arrow wound' (all three devolve into Pāli with the same spelling); and that we should avoid translating this as 'surgeon', because here, anyway, it seems to be an adjective rather than a noun. It's not inconceivable that an arrow maker might also have found employment as a remover of arrows, being conversant with arrows. Just as a medieval European barber found other employment for their razor (though again calling this 'surgery' is over the top).

All this means that we do not have to impose two patients on the verb, and that bhisakkaṃ sallakattaṃ is a straightforward apposition 'an arrow removing doctor'.

What does sallakattaṃ mean? The salla part means 'arrow' (which is what the whole thing is about) and this leaves us with -katta. According to BL "the only phonological explanation for the -tt- is if the geminate replaced an original conjunct consonant. The only one that would be contextually relevant is the noun karta [from √kṛt 'to cut'] which means "hole, cavity." Hence sallakatta must refer to the 'arrow wound'. This reading requires the verb to take two patients, and it's not clear whether this is allowed. DOP lists no examples of this.

BL notes that Buddhadatta concise Pāli-Eglish Dictionary defines sallakata as 'surgeon' (and sallakattiya as 'surgery', on the basis, apparently that salla can mean a surgical instrument. PED derives katta from *kartṛ 'worker' (the word exists in Skt. so I'm not sure why they use the asterisk). However the obvious meaning of sallakartṛ would be 'arrow maker' or 'fletcher', rather than surgeon. Compare MW śalyakartṛ 'arrow maker'; but śalyakarttṛ 'a remover of splinters, i.e. a surgeon'. Apte's English Sanskrit Dictionary suggests śalyataṃtravid and śasravaidyaḥ for surgeon. I think the answer is that Pāli sallakatta is Skt. śalyakarttṛ 'arrow remover' rather than śalyakartṛ 'arrow maker' or śalyakarta 'arrow wound' (all three devolve into Pāli with the same spelling); and that we should avoid translating this as 'surgeon', because here, anyway, it seems to be an adjective rather than a noun. It's not inconceivable that an arrow maker might also have found employment as a remover of arrows, being conversant with arrows. Just as a medieval European barber found other employment for their razor (though again calling this 'surgery' is over the top).

All this means that we do not have to impose two patients on the verb, and that bhisakkaṃ sallakattaṃ is a straightforward apposition 'an arrow removing doctor'.

Bow

Moving on we come to the bow. Most translators cope well with this sentence. There are in fact three words: dhanu, cāpa and kodaṇḍa. The first two are synonyms, though dhanu (Skt. dhanus) is also a word for 'rainbow'; and may be related to words for trees, c.f. dāru 'wood'. PED suggests that the word cāpa, by contrast, comes from a root meaning 'to quiver' from PIE *qēp. However, my new Sanskrit etymological dictionary, Kurzgefaβtes etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindischen (CSED), suggests *kēp or *kamp. The root *kēp does not occur in my standard PIE sources, but *kamp does and it means 'to bend' (AHD/OIEL).

A kodaṇḍa is according to PED a 'cross bow' though it is doubtful whether the technology existed in the Buddha's time; c.f. DOP 'a kind of bow'; MW & Böhtlingk who both define it as 'bow' with no mention of 'crossbow'. CSED makes the obvious point that daṇḍa is a stick, or staff, but adds that ko- here is a pejorative prefix (a form of Skt. ku) so that it must mean something 'bad stick'. Note that the Chinese version of the text does not mention the cross-bow although they clearly had them by the time the translation was made. BL's suggestion is that kodaṇḍa is a loan word from Munda and refers to the bows that the Munda speaking peoples used. Certainly daṇḍa appears to be a loan word (C.f Witzel 1999, p.16) [I have one more ref to check on this JR]

A kodaṇḍa is according to PED a 'cross bow' though it is doubtful whether the technology existed in the Buddha's time; c.f. DOP 'a kind of bow'; MW & Böhtlingk who both define it as 'bow' with no mention of 'crossbow'. CSED makes the obvious point that daṇḍa is a stick, or staff, but adds that ko- here is a pejorative prefix (a form of Skt. ku) so that it must mean something 'bad stick'. Note that the Chinese version of the text does not mention the cross-bow although they clearly had them by the time the translation was made. BL's suggestion is that kodaṇḍa is a loan word from Munda and refers to the bows that the Munda speaking peoples used. Certainly daṇḍa appears to be a loan word (C.f Witzel 1999, p.16) [I have one more ref to check on this JR]

Bow String

| Calotropis gigatea |

Pāli akka is Calotropis gigantea (Skt. arka). Variously called in English “calotrope, crown flower, giant milkweed, swallow-wort, and apple of Sodom.” Chiefly notable in the present for its milky sap, which has medicinal properties, and for its attractive flowers; in the past the leaves were used in Vedic ceremonies, and apparently the plant produced fibers strong enough to be woven into bowstrings. The last item in the list is Pāli khīrapaṇṇin, but this is simply a synonym for akka; literally meaning ‘having leaves with milky sap’. Ñ&B translate it as ‘bark’; MA informs us that bowstrings were made from the bark (vāka) of the akka – though as a flowering shrub it doesn’t have bark per se, so here it must mean the outer layers of the stems. Compare the notion of ascetics wearing the vākacīra or ‘bark garment’, which presumably is from cloth woven of rough fibre produced from this or a similar source. According to the Udāna-Aṭṭakathā, Bāhiya used akka stalks (akkanāḷāni) to make a robe and shawl (nivāsana-pāvuraṇāni) to clothe himself. akkanāḷāni chinditvā vākehi paliveṭhetvā nivāsanapāvuraṇāni katvā acchādesi (UdA 77).

Pāli nhāru is a variant spelling of nahāru meaning 'sinew'. Sinew is, of course, the connective tissues from animals, particularly tendons. It's possible that 'gut' might be included under this heading, since as we know stringed instruments used to (and sometimes still do) use gut strings and these are able to bare considerable tension.

|

| Sanseveria roxburghiana |

Pāli maruvā is a plant of the genus Sanseveria (also spelt Sansevieria) specifically S. roxburghiana. One of the characteristic plants of this genus is the ornamental ‘mother-in-law’s tongue’ (S. trifasciata). Sometimes called ‘bowstring hemp’, though not related to the cannabis plant. Other names for the genus include: dragon’s tongue, jinn’s tongue, snake tongue, etc. Some species are excellent sources of fibre, and used for making rope (and bow strings) in India and Africa. For an illustration of how fibres were obtained from such plants see: primitiveways.com.

The Chinese substituted various kinds of sinew (筋) at this point in their text.

The Chinese substituted various kinds of sinew (筋) at this point in their text.

Shaft

| Saccharum sa |

Pāli gaccha ‘a shrub or bush’. MA ‘from a mountain bush or river bush etc.’ (pabbatagaccha-nadīgacchādīsu jātaṃ). PED gaccha ‘shrub, bush’ often in comparison with trees (rukkha) and vines (latā); PED denies the confusion with Skt. kaccha; (PED Sv. kaccha ‘pabbatakaccha & nadīkaccha mountain & river marshes’).

Pāli ropima ‘what has been planted’. MA ‘having sown, raised, desiring sara; having got sara, [the arrow] was made’ (ropimanti ropetvā vaḍḍhitaṃ saravanato saraṃ gahetvā kataṃ.). Pāli sara is Saccharum sara (aka muñja grass) which sends up long (2m) tufted spears that can be made into arrows. Alternatively ‘desiring sara’, saravanato, could be ‘from a grove (vana) of sara’ - though does grass grow in 'groves'? Ñ&B, following MA, understand this and previous term to mean “wild” and “cultivated”.

The Chinese have three options: muñja grass, bamboo and luó é lí wood (羅蛾梨木) though I could not produce a plausible translation for the last.

Pāli ropima ‘what has been planted’. MA ‘having sown, raised, desiring sara; having got sara, [the arrow] was made’ (ropimanti ropetvā vaḍḍhitaṃ saravanato saraṃ gahetvā kataṃ.). Pāli sara is Saccharum sara (aka muñja grass) which sends up long (2m) tufted spears that can be made into arrows. Alternatively ‘desiring sara’, saravanato, could be ‘from a grove (vana) of sara’ - though does grass grow in 'groves'? Ñ&B, following MA, understand this and previous term to mean “wild” and “cultivated”.

The Chinese have three options: muñja grass, bamboo and luó é lí wood (羅蛾梨木) though I could not produce a plausible translation for the last.

Feathers

For an arrow to fly true it needs some stabilising fins or vanes at its base. Traditionally these were made from feathers. In our allegory the feathers might have come from the vulture, heron, falcon, peacock, or sithilahanu. The latter is a mystery.

Ñ&B translate sithilahanu as ‘stork’, but on what authority? The name is a hapax legomenon (a one off) in the Canon. Buddhaghosa's commentary (MA) merely says ‘a bird of that name’ (evaṃ nāmakassa pakkhino)! The sub-commentary (MṬ) ‘Sithilahanu is the name given for an bird with ears(?)’ (sithilahanu nāma dattā kaṇṇo pataṅgo) where kaṇṇa means ‘angle, corner; ear; rudder’; pataṅga is not in PED, but the CST dictionary lists ‘a bird’ (c.f. Skt. pataṃga ‘flying; any flying insect’). PED sv. sithila ‘loose, lax’; and sithilahanu ‘a kind of bird’. Sithilahnu is not in DOPN; nor is the Sanskrit (śithirahanu/śithilahanu) in MW. Searching PED electronically reveals no occurrence of the word ‘stork’. Buddhadatta’s English-Pāli Dictionary sv. stork gives ‘bakavisesa’; while Apte’s English-Sanskrit dictionary gives nothing like sithilahanu for 'stork'. Thomas (1913) and Gethin (2008) leave the word untranslated; c.f. Horner (1954-9) “some other bird” (vol.2, p.99). Note that also in our text we have the name kaṅkha 'heron' (from √kaṅk which may have an onomatopoeic origin).

The Chinese version of this text (Taisho T.01 n.94 p.0917c21) records the name as 鶬鶴 (cāng hè) which is Grus monacha, the Black or Grey Crane. However the text only includes three names: peacock (是孔雀), black crane (鶬鶴), and eagle (鷲). So cāng hè could just as easily be a substitute for heron as for stork, and indeed G. monacha could be said to more closely resemble a heron.

There is a suggestion that sithilahanu refers to the open billed stork (Anastomus oscitans). This is mentioned in a blog post by Shravasti Dhammika for instance. The Envis Centre on Avian Ecology in collaboration with the Bombay Natural History Society lists "shithil hanu bak" as the Sanskrit name of the A. oscitans. This has obviously been Hindi-fied and ought to be śithilahanubaka. But where has this come from?

If we translate sithalahanu it means something like 'slack jawed' (hanu is cognate with the English chin) which might plausibly be a reference to the open billed stork since it's lower beak does not quite fit the upper leaving a gap. Sanskrit-English and Pāli-Eng. dictionaries only include the more gracile herons and cranes under the name baka; but Eng-Skt. and Eng-Pāli dictionaries include baka as a name for the stork.

Ali & Ripley in their authoritative guide to India birds (2001), give the Hindi name of A. oscitans as Gūnglā, Ghonghila, or Ghūngil. Hindi etymology is difficult to establish but Skt. ghoṇa 'beak, nose', Skt gila 'swallowing' might allow for a hypothetical Skt. *ghoṇagila(?). Though there is nothing like this in either my Pāli or Sanskrit dictionaries. The Bengali names are given as Thonte Bhānga, Shāmukh Bhānga, Shāmukh Khol. Here I've had more luck (with help from a young naturalist): ṭhōnṭa 'beak'; śāmukh 'mollusc'; bhaṅga 'breaking'; khol 'cover; shell; hollow, crevice, open' (e.g. চোখের খোল (cokhera khola) 'eye socket'; and পেটের বা বুকের খোল (peṭera bā bukera khola) 'chest cavity'.) Which gives us Thonte Bhānga 'broken beak'; Shāmukh Bhānga 'mollusc breaker'; or Shāmukh Khol 'mollusc hollow(?)' as possible names. The Tamil name is Naththai kuththi narai 'Snail Pecking Stork'. The Bihari name is given as Dokar, but I cannot find any more information on this word. So none of the modern Indian names of the bird resemble sithilahanu, either in form or content.

In tracing this further I think I found the source of the equation of sithalahanu and the open-billed stork. In his 1949 book on bird names, celebrated Indian scholar Raghu Vīra lists (entry 2215, p. 426) Anastomus oscitans as घोंघाशा शिथिल-हनु (ghoṃghāśā śithila-hanu) and then slightly below as शिथिल बक (śithila baka). At first sight this would seem to be definitive, but we note that Vīra does not list any Sanskrit sources. In his notes he only refers to a yet-to-be-published book by K. N. Dave seen in manuscript which referred to the stork by this name. This book was subsequently published (apparently posthumously in 1985) and it reveals something interesting about the Sanskrit name of A. oscitans (p.395-6). In trying to identify the open billed stork in Sanskrit literature Dave tentatively identifies a number of other candidate names, but these are by no means certain. Significantly he does not list śithilahanu as a Sanskrit name, suggesting that he did not find it in any Sanskrit text. However he has noticed the Pāli bird name sitihlahanu which translates as 'having a lower mandible loose or relaxed' and says

In fact there is nothing 'loose or relaxed' about the very robust bill of the stork (have another look at the picture above) it just doesn't fit together. 'Loose' is hardly a "fitting or correct rendering" of 'open' when you stop to think about it. These unjustified leaps are given a seal of approval by the great Raghu Vīra and it becomes a "fact" that the Sanskrit name is śithilahanu, or reading the Devanāgarī Hindi fashion: Shithil Hanu.

Unfortunately connection is entirely spurious, and this means that, after a thorough search, I can find no authority for translating sithilahanu as 'stork' or 'open-billed stork'. The word sithilahanu appears to be lost to us unless some new evidence should emerge.

|

| Grus monacha |

There is a suggestion that sithilahanu refers to the open billed stork (Anastomus oscitans). This is mentioned in a blog post by Shravasti Dhammika for instance. The Envis Centre on Avian Ecology in collaboration with the Bombay Natural History Society lists "shithil hanu bak" as the Sanskrit name of the A. oscitans. This has obviously been Hindi-fied and ought to be śithilahanubaka. But where has this come from?

If we translate sithalahanu it means something like 'slack jawed' (hanu is cognate with the English chin) which might plausibly be a reference to the open billed stork since it's lower beak does not quite fit the upper leaving a gap. Sanskrit-English and Pāli-Eng. dictionaries only include the more gracile herons and cranes under the name baka; but Eng-Skt. and Eng-Pāli dictionaries include baka as a name for the stork.

|

| Anastomus oscitans |

In tracing this further I think I found the source of the equation of sithalahanu and the open-billed stork. In his 1949 book on bird names, celebrated Indian scholar Raghu Vīra lists (entry 2215, p. 426) Anastomus oscitans as घोंघाशा शिथिल-हनु (ghoṃghāśā śithila-hanu) and then slightly below as शिथिल बक (śithila baka). At first sight this would seem to be definitive, but we note that Vīra does not list any Sanskrit sources. In his notes he only refers to a yet-to-be-published book by K. N. Dave seen in manuscript which referred to the stork by this name. This book was subsequently published (apparently posthumously in 1985) and it reveals something interesting about the Sanskrit name of A. oscitans (p.395-6). In trying to identify the open billed stork in Sanskrit literature Dave tentatively identifies a number of other candidate names, but these are by no means certain. Significantly he does not list śithilahanu as a Sanskrit name, suggesting that he did not find it in any Sanskrit text. However he has noticed the Pāli bird name sitihlahanu which translates as 'having a lower mandible loose or relaxed' and says

"I need hardly add that शिथिलहनु [śithilahanu] is a most fitting name and a correct rendering of the English name Open-bill for the bird." (p.396)Dave has performed a remarkable slight of hand here. Although there is no traditional equation of the open billed stork with sithilahanu that I can find, or that he cites, he has made the leap and connected them. Then in another great leap he equates the Pāli with the Sanskrit, spelling the Pāli word in the Sanskrit manner, and somehow śithilahanu becomes the perfect name for the bird, even though this Sanskrit name does not exist, and there is no a priori reason to believe that the Pāli name refers to this bird! Indeed his enthusiasm rests partly on the way that his invented Sanskrit spelling fits the English.

In fact there is nothing 'loose or relaxed' about the very robust bill of the stork (have another look at the picture above) it just doesn't fit together. 'Loose' is hardly a "fitting or correct rendering" of 'open' when you stop to think about it. These unjustified leaps are given a seal of approval by the great Raghu Vīra and it becomes a "fact" that the Sanskrit name is śithilahanu, or reading the Devanāgarī Hindi fashion: Shithil Hanu.

Unfortunately connection is entirely spurious, and this means that, after a thorough search, I can find no authority for translating sithilahanu as 'stork' or 'open-billed stork'. The word sithilahanu appears to be lost to us unless some new evidence should emerge.

Binding

| |||

| Ruru Jataka bas-relief |

Next our man wants to know about the binding used for the feathers, and again we are left with some mysteries. The choices are the sinews of the cow (gava), buffalo (mahiṃsa), something called roruva (or in CST bherava), and something called semhāra.

CST has bherava ‘fearful, terrible’, which MA glosses as kāḷasīha ‘black lion’ (the Asiatic lion can apparently be a mottled black in colour); other editions have roruva ‘deer’ (the two words are in fact related from the root √ru ‘roar’ [as is the -rava part of my Sanskrit Name]. Male deer do roar in the rutting season, to attract mates and warn off rivals.) Roruva is the name of a hell realm (DOPN). Skt. ruru is a kind of antelope, but can refer to savage animals in general.

Under semhāra PED "some sort of animal (monkey?)", noting that it is explained as makkaṭa (monkey) by Buddhaghosa's commentary. The Sanskrit markaṭa is also ‘the Indian crane, a spider, and a sexual position’). This word is also a hapax legomenon in the Canon and my research has not turned up anything interesting. There is no Sanskrit equivalent that I can find, unless semhāra is related to, or a dialectical form of the Sanskrit siṃha 'lion' (Pāli 'e' is the guṇa and vṛddhi grade of 'i'); though note that Gāndhārī spells it siṃha. Like sithilahanu this word seems to be lost to us.

CST has bherava ‘fearful, terrible’, which MA glosses as kāḷasīha ‘black lion’ (the Asiatic lion can apparently be a mottled black in colour); other editions have roruva ‘deer’ (the two words are in fact related from the root √ru ‘roar’ [as is the -rava part of my Sanskrit Name]. Male deer do roar in the rutting season, to attract mates and warn off rivals.) Roruva is the name of a hell realm (DOPN). Skt. ruru is a kind of antelope, but can refer to savage animals in general.

Under semhāra PED "some sort of animal (monkey?)", noting that it is explained as makkaṭa (monkey) by Buddhaghosa's commentary. The Sanskrit markaṭa is also ‘the Indian crane, a spider, and a sexual position’). This word is also a hapax legomenon in the Canon and my research has not turned up anything interesting. There is no Sanskrit equivalent that I can find, unless semhāra is related to, or a dialectical form of the Sanskrit siṃha 'lion' (Pāli 'e' is the guṇa and vṛddhi grade of 'i'); though note that Gāndhārī spells it siṃha. Like sithilahanu this word seems to be lost to us.

Arrowhead

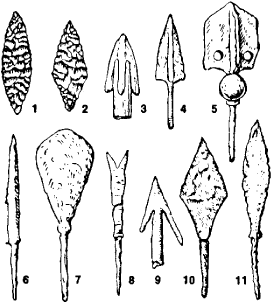

The arrow heads have produced the least informative translations, but it's possible to reconstruct what the terms might have meant by casting our net a bit wider than PED, and by looking at the shapes that arrow heads traditionally take. In Pāli we have: salla, khurappa, vekaṇḍa, nārāca, vaccha-danta, and karavīra-patta.

Of these terms nārāca ‘iron’ seems to be the odd one out, though the Sanskrit Epics mention arrows of iron which were used to kill elephants (Singh p.105). The other names seem to concern shape of the arrow head:

|

| various arrow heads |

- the salla is a simple point [c.f. no. 6, right].

- khurappa (PED ‘hoof’) is the Epic Skt. kṣurapra ‘knife edged’ arrow [c.f. 4] (Singh 1989, p.105) and hence Ñ&B have read this too literally, or been mislead by PED. Note that Cone's new DOP gets this right and lists it under khura1 'a razor or sharp blade'.

- vekaṇṇa (barbed); [9]

- vaccha-danta calf’s tooth (Skt vatsa-danta) is mentioned in the Epics and said to be in the shape of a calf’s tooth [similar to 7] and extremely sharp (Singh 1989, p.105);

- karavīra-patta or oleander leaf, the shape of which is technically described as ‘narrow lanceolate’, i.e. a narrow, elongated oval coming to a sharp point. [11]

Conclusion

Why should we care about such details in a text which is primarily making a metaphysical point about what kinds of questions are answerable and/or important to ask? For most people, and most translators judging by their approach to this text, the answer seems to be that the details are irrelevant, which is to take the message of the text rather literally. After all I am not pierced by an arrow, or trying to emotionally blackmail anyone, I'm trying to translate a text so as people who don't know Pāli can read it. I'm not Māluṅkyaputta. I'm not refusing to practice unless I find the answers, but I am interested, and enjoy the investigative process.

I think what made me spend time looking into these questions is that the poor quality of the other translations jarred, and disrupted my sense that the text was a living document. The lack of concern for preserving knowledge of small details has meant that we have lost any hope of definitively understanding them - I can speculate, but in the long run neither I nor anyone can reconstruct terms that were lost unless some new evidence should emerge - perhaps a Gāndhārī version of the text for instance.

I think what made me spend time looking into these questions is that the poor quality of the other translations jarred, and disrupted my sense that the text was a living document. The lack of concern for preserving knowledge of small details has meant that we have lost any hope of definitively understanding them - I can speculate, but in the long run neither I nor anyone can reconstruct terms that were lost unless some new evidence should emerge - perhaps a Gāndhārī version of the text for instance.

It might be argued that losing Pāli terms for archery is no great loss, but if we get these details wrong through indifference then what other details are we getting wrong? How many of us, for example, picture Bahiya going around draped with great lumps of tree bark instead of roughly spun jute cloth? Keeping the past alive, or bringing it to life, means making use of such details to give our picture resolution. Why settle for vague blur when we can do considerably better than that?

I think word extinction is a problem. Perhaps not a huge problem, if one tree dies, we still have the forest, but it's a sign of carelessness, or neglect. If we value these texts for what ever reason, then there is an imperative not just to preserve them, but to keep alive what they mean. If we allow a words to cease being meaningful, then the whole is marginally less complete and less beautiful. Most likely we'll never recover what has been lost.

~~oOo~~

What follows is a very rough rendering of the same passage from the Chinese text (Taisho T.01 n.94 p.0917c21) from CBETA, using online translation (often ludicrous), dictionaries, pattern recognition, and some guess work on the basis that it can't be that different from the Pāli. Notes on each paragraph are included below it in bullet points. While the grammar is less than crystal clear, one can pick out key words, the nouns and adjectives, which is all we need for a general comparison. The caveat is that I only know a handful of Chinese characters (and that from my interest in Japanese). MO = notes by Maitiu O'Ceileachair.

I cannot remove the arrow (我不除箭) until I know of the one who shot me (誰以箭中我): what was his surname (姓), his name/mark(?) (字); was he long (長) or short (短); if he was dark (黑) or pale (白); kṣtriya (剎利), Brahmin (婆羅門), layman (居士), or worker (工師姓); from the East (東方), South (南方), West (西方) or north (北方)?

- The 字 is what is usually known as the style name, that used to be taken by a man at 20. Here it just means name. (MO).

- 剎利 shālì = kṣatriya

- 婆羅門 póluómén a phonetic rendering of brāhmaṇa.

- 居士 Jūshì = lay, scholar, Buddhist.

In addition I cannot remove the arrow (我不除毒箭) until I know: was the bow sala wood (薩羅木), tala wood (多羅木), or chì luó yāng jué lí wood (翅羅鴦掘梨木)?

- sà luó i.e. Skt. sala.

- duō luó: Skt. tala i.e. palmyra

- chì = ke, ki, ḍa; luó = la, ra; yāng = aṇg; jué = ku, gu; lí = ri. Karungali? (Acasia catechu) Keralan name; c.f. kirankuri (Emilia sonchifolia) a herb in Hindi.

In addition I cannot remove the arrow until I know: were the sinews (筋) which wrapped the bow (而用纏彼弓) beef sinew (若牛), sheep sinew (羊筋), or yak sinew (氂牛筋)?

In addition I cannot remove the arrow until I know: was the bow grip (弓弝) white bone (白骨), black lacquer (黑漆), or red paint (赤漆)?

In addition I cannot remove the arrow until I know: was the bowstring (弓弦) beef sinew (牛筋), sheep sinew (羊筋), or yak sinew (氂牛筋)?

In addition I cannot remove the arrow until I know: is the arrow [shaft] Shě luó wood (舍羅木), bamboo (竹), or Luó é lí wood (羅蛾梨木)?

In addition I cannot remove the arrow until I know: is the arrow binding (纏箭) beef sinew (牛筋), sheep sinew (羊筋), or yak sinew (氂牛筋)?

- 舍羅 Shě luó = Skt. śara (Pāli sara) = Saccharum sara used for making arrows.

- Luó é lí = The first and last characters are used to transliterate ra and ri, but I haven't found an example of 蛾 used this way. Literally the characters read 'gather moth pear'.

In addition I cannot remove the arrow until I know: are feathers (毛羽 used to make the vanes (取彼翅用作羽), peacock (孔雀), black crane (鶬鶴), or eagle (鷲)?

In addition I cannot remove the arrow until I know: was it iron (鐵), or calf [tooth] (婆蹉), póluó (婆羅), or nàluó 那羅, or jiāluó bǐng (伽羅鞞)?

- 婆蹉 pó cuō is a translation of vātsīputriya; c.f. Pāli vatsa 'calf'. Burnouf & Buffetrille (2010), p.518.

- 婆羅 = póluó = Skt. pāla, bāla, bala, sāra.

- 那羅 = nàluó; = Skt. na ra; c.f. 緊那羅 kinnara; cf. Pāli nārāca 'iron'.

- 伽羅鞞 jiāluó bǐng = Skt karavī[ra]?; cf. Pāli karavīra-patta 'oleander shaped leaf'.

In addition I cannot remove the arrow until I know: what was the blacksmith's (鐵師) last name (姓); long or short; dark or pale; in the East, South, West or north?Despite considerable obscurity remaining, most of the content of the text can be identified. Even without fully understanding the Chinese we can see that the form is much the same as the Pāli text, but that content is mostly quite different. The Chinese translators have used two different methods to deal with unfamiliar words or entities. Firstly they transliterate using a Chinese character (汉字 hànzì) to represent the sound, e.g. 婆羅門 póluómén for brāhmaṇa; secondly they substitute with something more familiar, as with black crane (鶬鶴) for heron (kaṅka).

- I think 鐵師 means 'blacksmith'. It occurs quite frequently in the canon and from context it usually seems to refer to a craftsman of some sort. (MO)

It's useful to know that Chinese translators sometimes transliterated and I'm grateful to my friend Maitiu O'Ceileachair for many long discussions about the ins and outs of this and other translation issues (and thanks for giving me a few pointers post publication, noted above). I'm also grateful to the anonymous person who extracted many examples of the Chinese translation approach from the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism (which has an incomprehensibly restrictive access policy).

A final note is that we can tell from the way of the words are transliterated that the original the Chinese translators were working from was not in Pāli, but in Sanskrit, or a more Sanskrit-like Prakrit. For instance when transliterating sara the 's' is aspirated (sh)--舍羅 shě luó--which is not a feature of Pāli, but compare the Sanskrit equivalent, śara, which is aspirated, and note that the Gāndhārī Dhammapada (G-Dhp 329) has śara for the Pāli saraṃ 'arrow' (Dhp 320). At least some of the texts reaching Chinese were written in Gāndhāri (c.f. Boucher 1998)

Bibliography

- Environmental Information System (ENVIS) Online: http://www26.us.archive.org/details/IndianBirdNames.

- Ali, Sálim and Ripley, Dillon S. (2001) Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan: together with those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka. Bombay Natural History Society.

- Ānandajoti. (2007) A Comparative Edition of the Dhammapada: with parallels from Sanskritised Prakrit edited together with A Study of the Dhammapada Collection. (2nd rev. ed.) Online: http://www.ancient-buddhist-texts.net/Buddhist-Texts/C3-Comparative-Dhammapada/index.htm.

- Biswas, Sailendra. (2000) Samsad Bengali-English dictionary. 3rd ed. Calcutta, Sahitya Samsad. Online http://dsal.uchicago.edu/dictionaries/biswas-bengali/

- Boucher, Daniel. (1998). 'Gāndhārī and the Early Chinese Buddhist Translations Reconsidered: The Case of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra.' Journal of the American Oriental Society, 118 (4): 471-506. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/604783

- Buddhadatta. (1955) English-Pali Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass, 1989.

- Burnouf, Eugène & Katia Buffetrille [trans]. (2010) Introduction to the History of Indian Buddhism, University of Chicago Press. Originally published as Introduction à l'histoire du buddhisme indien, Paris: Imprimerie Royale, 1844.

- Dave. K. N. (1985) Birds in Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Dictionary of Pali Names [DOPN]

- Childers, R. C. (1875) A Dictionary of Pāli language. London: Trubner & Co.

- Gethin, Rupert. (2008). Sayings of the Buddha. Oxford University Press.

- Horner, I. B. (1954-9) The Book of Middle Length Sayings. (3 vols.) Pali Text Society.

- Ñānamoli and Bodhi. (2001). The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha. 2nd ed. Wisdom.

- Singh, Sarva Daman. (1989) Ancient Indian Warfare: With Special Reference to the Vedic Period. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Vīra, Raghu. (1949) Indian Scientific Nomenclature of the Birds of India, Burma and Ceylon. International Academy of Indian Culture.

- Witzel, Michael. (1999) 'Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Ṛgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic).' Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies (EJVS) 5(1): 1–67