I've been thinking a lot about how a failure to understand science affects the arguments against materialism. In Buddhism we often make the argument that you cannot understand Buddhism unless you have practised it. By the same token we might argue that unless one has practised science one can hardly be expected to fully understand it. And as a result many people have naive and unsophisticated views about what science is.

If more people had a positive experience of discovering empirical laws for themselves in school that we might be having a very different discussion about religion and science right now. Unfortunately most of us learn science in large classes aimed at middling students, from average teachers who may or may not have become jaded by the grind of the job. In the end most of don't actually learn any science. But for me learning science was always a joy. I want to see if I can communicate something of this.

Take the humble substance, water. Water is remarkable stuff. We all know this. We might know that ⅔ of the earth is covered in it, and that our bodies are 80% water. We know that it's essential to life of earth, that in many ways it is the medium for life. Most scientists believe that life on earth must have started in water. The properties of water are:

- Water is a liquid at standard temperature (20°C) and pressure (1 atmosphere).

- Under STP it freezes, i.e. becomes a solid, at 0°C STP; and it boils, i.e. becomes a gas, at 100°C.

- Water is an excellent solvent and able to dissolve most minerals.

- Water is an electrical conductor and with even small impurities can be an excellent conductor.

- Liquid water has a high-surface tension so that it forms relatively large drops.

- Water is moderately chemically stable - it doesn't easily react with other chemicals.

- Water ice can take as many as 15 different forms depending on the conditions.

- Water vapour is a major contributor to the greenhouse effect.

The water molecule is represented by the chemical formula H2O. This means that each water molecule contains one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. The two hydrogen atoms attach to the oxygen on one side about 105° apart from each other. I look at the reasons for this shortly.

But how do we know all of this? Isn't it all just some theory? Well, no. It's not all "just theory". It certainly involves interpretive theory, but most of it is either from direct observation, or deductions from indirect observations. I'll try to explain how we know about the water molecule.

|

electrolysis |

2 H2 + O2 ⇌ 2 H2O

If we use pure water this is always true. Impurities do change the result slightly. But anyone can take a battery and two wires and pass electricity through water and see bubbles forming. And bubbles at one electrode will always behave like oxygen (for example will make a flame glow brighter) and bubbles at the other will always behave like hydrogen (react explosively with air), and there will always be twice as much hydrogen as oxygen. Always.

One of the important things to note is that water has properties as a compound that neither of it's component parts, oxygen and hydrogen, have or even hint at. That two gases would combine to form a liquid with entirely different physical and chemical properties is an important observation. With 20th centuries theories we not only understand this but have successfully predicted the properties of new elements and compounds.

One of the important things to note is that water has properties as a compound that neither of it's component parts, oxygen and hydrogen, have or even hint at. That two gases would combine to form a liquid with entirely different physical and chemical properties is an important observation. With 20th centuries theories we not only understand this but have successfully predicted the properties of new elements and compounds.

|

emission spectra |

The structure of the water molecule is deduced by combining information from many sources. For example we might look at the six-fold (hexagonal) symmetry of snow flakes. There's only a limited number of configurations of molecules that could produce this shape. Or we can take a crystal and shine X-rays through it and measure how the X-ray beam is scattered. Different kinds of crystal give characteristic scattering patterns. This was how Rosalind Franklin deduced that DNA must be a helix. (here is her original 1953 paper). In fact water-ice can form with 15 different crystal structures depending on the temperature and pressure when it forms. (See Ice: phases)

We can also deduce something important from what kinds of substances water will mix with and what it will dissolve. For example we know that water and alcohol mix completely and can only be separated out by distillation - which involves boiling the mixture. Ethyl alcohol boils at 78°C so it boils first and turns into a gas that drifts away from the liquid. However water will not mix with oily substances. Water will dissolve rock given time, but not wax.

|

| NASA |

There's a neat trick you can do that helps to explain this. We all know about static electricity. If you rub plastic with a natural fabric the difference in electrical properties causes a transfer of electrons and the build up of a static electrical charge. If you wear nylon clothing your whole body can build up a charge that discharges when you touch another person or a door handle (for example). If you charge up a balloon with a good amount of static by rubbing it on someone's clean dry hair (which is entertaining in it's own right) and bring it close to a stream of water, the stream will bend towards the balloon. It turns out that water is able to be attracted by an electric charge. But oils and fats are not.

|

| CO2 |

We can get a better understanding of water by comparing similar compounds, especially those involving atoms nearby in the periodic table. For example might look at hydrogen compounds of carbon, nitrogen and fluorine on the same row, and sulphur in the row below. If we look at how each of these elements combine with hydrogen we find that carbon forms a compound CH4, (methane); nitrogen forms NH3 (ammonia) and fluorine forms FH (hydrogen fluoride). So there is a pattern here: 4, 3, 2, 1. Sulphur forms a compound H2S (hydrogen sulphide; aka rotten-egg gas), just as oxygen combined with hydrogen in a 2:1 ratio. In fact one of the reasons sulphur is in the same column of the periodic table is precisely because it forms H2S and not H3S or HS.

Clearly the naming conventions are a bit mixed - common names, legacy chemical names, and modern notations compete. If FH is called "hydrogen fluoride" despite the formula being FH "fluorine hydride". If they fit the pattern above H2O and H2S really ought to be OH2 (oxygen dihydride) and SH2 (sulphur dihydride) but they never are.

By comparing the physical properties of all these we get further insights. CH4 is a gas at room temperature, highly combustible in oxygen but otherwise quite chemically stable, and insoluble in water. NH3 is also a gas at room temperature, strongly reactive with other chemicals, and is highly soluble in water. FH boils at 19°C; it is highly water soluble forming hydrofluoric acid and extremely reactive (hydrofluoric acid is used for etching glass which is not touched by concentrated sulphuric or nitric acids).

Thus we can deduce that carbon with its fourfold symmetry forms a more stable molecule. And we known that carbon forms more kinds of compounds than any other element - it is the basis of organic chemistry.

By comparing the physical properties of all these we get further insights. CH4 is a gas at room temperature, highly combustible in oxygen but otherwise quite chemically stable, and insoluble in water. NH3 is also a gas at room temperature, strongly reactive with other chemicals, and is highly soluble in water. FH boils at 19°C; it is highly water soluble forming hydrofluoric acid and extremely reactive (hydrofluoric acid is used for etching glass which is not touched by concentrated sulphuric or nitric acids).

Thus we can deduce that carbon with its fourfold symmetry forms a more stable molecule. And we known that carbon forms more kinds of compounds than any other element - it is the basis of organic chemistry.

If 4 objects surround a fifth symmetrically they occupy the points of a tetrahedron - the internal angle between each would be 120°. So as a first approximation we might expect NH3 to be a tetrahedron minus one point (or a three sided pyramid with N at one apex). Again, if the H atoms in NH3 were evenly distributed around the Nitrogen we'd expect different properties (e.g. less soluble in water). For the two H atoms in a water molecule to be about 120° apart. In fact as I said they turn out to be 104.5°.

The mathematical models for atoms predict that each electron will have a distinctive energy. But also they will allow for pairs of electrons with different "spin" (an abstract physical property the consequences of which are observable in subtle experiments, but which would take a long time to describe). Hydrogen has only one electron and is highly reactive with almost anything that can accept an electron. Helium atoms with two electrons are very reluctant to form any chemical bonds. They occupy opposite ends of the first row of the periodic table. It turns out that if we add a third electron, as in lithium (Li) then we once again get a highly reactive atom. But atomic carbon with six (2 + 4) electrons is relatively stable and fluorine with nine (2 + 7) electrons is once again highly reactive and neon with 10 (2 + 8) electrons is almost completely inert.

The pattern is consistent with different types of orbitals for electrons. The first (s) orbital takes 2 electrons and is more or less spherical. The second (p) orbital takes 8 electrons, in 4 pairs. We can guess from the kinds of molecules they form (and the crystal structures of those molecules) that these orbitals form a tetrahedron. (In fact there is a difference between atomic and molecular electron orbitals, but we'll focus on the molecular orbitals). The shape of these orbits are relatively inflexible which is partly why water and ammonia are asymmetrical.

The mathematical models for atoms predict that each electron will have a distinctive energy. But also they will allow for pairs of electrons with different "spin" (an abstract physical property the consequences of which are observable in subtle experiments, but which would take a long time to describe). Hydrogen has only one electron and is highly reactive with almost anything that can accept an electron. Helium atoms with two electrons are very reluctant to form any chemical bonds. They occupy opposite ends of the first row of the periodic table. It turns out that if we add a third electron, as in lithium (Li) then we once again get a highly reactive atom. But atomic carbon with six (2 + 4) electrons is relatively stable and fluorine with nine (2 + 7) electrons is once again highly reactive and neon with 10 (2 + 8) electrons is almost completely inert.

The pattern is consistent with different types of orbitals for electrons. The first (s) orbital takes 2 electrons and is more or less spherical. The second (p) orbital takes 8 electrons, in 4 pairs. We can guess from the kinds of molecules they form (and the crystal structures of those molecules) that these orbitals form a tetrahedron. (In fact there is a difference between atomic and molecular electron orbitals, but we'll focus on the molecular orbitals). The shape of these orbits are relatively inflexible which is partly why water and ammonia are asymmetrical.

|

| Wikimedia |

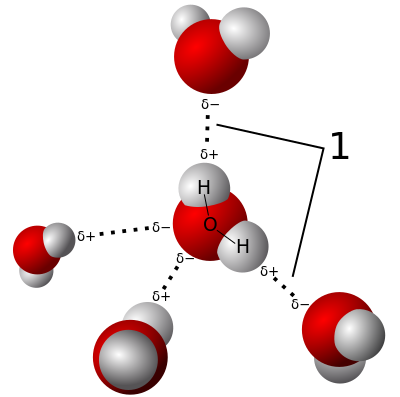

In any case we now roughly know the shape of the water molecule and its electrical characteristics. And we can begin to relate these to some of its physical properties. For example the fact that water molecules are not symmetrical means that one end of the molecule as a slight negative charge and one end (the side with the two hydrogen atoms) has a small positive charge. This accounts for water's electrical conductivity. It also means that water molecules exert a weak attraction on each other - known as a "hydrogen bond" (indicated by a Greek delta δ in the picture). The positive ends of water molecules are attracted to the negative ends of others. This accounts for the surface tension of water. Water is very cohesive. In fact compared to similar liquids (methane, ammonia, or hydrogen sulphide as liquids) then water has a very high boiling point - indeed the other substances mentioned are all gases at room temperate. Ammonia NH3 boils at -33°C and hydrogen sulphide H2S boils (becomes a gas) at -60°C! So H2S is very different indeed from H2O. In order to break the attraction between water molecules one has to use a great deal more energy than to break the attraction between hydrogen sulphide molecules which are more or less the same shape. This also means that weight for weight water can absorb a lot of heat, which makes it useful as a cooling fluid in a variety of settings.

With the dawn of the 20th century mathematical models of atoms began to become more sophisticated and were able not only to explain the behaviour of atoms and molecules, but to make predictions. One of which was that a molecule like water would have many different ways it could vibrate: rolling, tumbling, spinning on its one symmetrical axis, stretching bonds symmetrically and asymmetrically, flexing the two bonds. And many others. And each of these modes of vibration was calculated to have a specific energy. It turns out that the energies of these modes of vibration fall in the infra-red/microwave part of the electro-magnetic spectrum. By shining infra-red light through water, and sweeping the frequency we can see what frequencies get absorbed, corresponding to making the water molecule wiggle, and refine the theory with observations. (See also Water Absorption Spectrum).

Spinning water molecules is also the explanation for how microwave ovens work. The microwave was patented in 1945 by Raytheon, though in fact it was discovered by mistake when a scientist working on radar melted his chocolate with his equipment. Apparently the first food to be deliberately cooked in a microwave oven was pop-corn. Water molecules spin around at ~ 2.4GHz (in the microwave part of the spectrum). Light at that frequency is absorbed by water molecules and translated into spinning, which manifests as heat (at the molecular level heat is equivalent to the speed of motion). Thus by shining microwave frequency "light" at 2.4 GHz on anything which contains water (like food) we can make it heat up.

|

vibrational modes of the water molecule. click image to see animation. |

|

| Bucky ball |

The theory also explained in detail why certain molecules took certain shapes and why for example the fourfold symmetry of methane was a particular stable configuration. By comparing theory to observation for all of the elements we have developed a very sophisticated description of the chemical compounds we know about. But it also enables us to predict new chemical compounds and to understand how we might make them. Buckminster-fullerene, so-called "bucky-balls", a form of carbon molecule with 60 carbon atoms arranged in hollow sphere with a structure like the domes designed by Buckminster-Fuller (or like a football), were synthesised using this knowledge. This knowledge has also helped to explain the structure and function of complex molecules like cortisone, oestrogen and testosterone.

Quantum mechanics makes for an even more detailed description of molecule although with detail comes complexity. Some of the insights of quantum theory have helped in understanding the electrical behaviour of semiconductors and super-conductors. But to return to water.

The unusual ability of water to remain in the liquid state that make it the idea medium for life. Similarly the ability of water to dissolve a range of gases, minerals and many organic compounds (sugars, alcohols, amino-acids, etc) without changing them chemically, make it the ideal medium for mixing a huge range of different chemicals such as we see in living cells (compounds which number well into the tens of thousands).

This is only the briefest of surveys of what I remember from a few years of studying chemistry applied to a single, though important and interesting molecule. We now have detailed descriptions of all of the 96 naturally occurring elements, many of the artificially created elements, and millions of chemical compounds and reactions. These descriptions underpin most of the industrial processes that have made the developed world wealthy. If you're inside and you look around, the products of this knowledge will surround you: from the structural materials of your house, to the paints and other decorative elements.

| Vanillin. Wikimedia |

In my 3rd year organic chemistry class we had two major practical tasks. In the first term we were handed a vial of white powder and asked to find out what it was using any means available to us. Using chemical and spectroscopic (scanning the stuff with infra-red light) and nuclear-magnetic resonance methods I determined that my unidentified white powder was vanillin, one the the two main compounds responsible for the smell and taste of vanilla. It could not be another compound. The evidence was completely specific. The conclusion was not the product of a narrative or a worldview. If anyone else had accurately tested it, at any time and place, they would have also have found vanillin.

|

| Coumarin Wikimedia |

So when people scoff at science I find it very peculiar. When people say it's just one narrative amongst many or than there is no objectivity in science, or (worse) that everything we know from science is subject to change, I can't help thinking that only a really ignorant person could say something like this. I've personally used all of the techniques mentioned above, done the practical experiments and derived the empirical laws. But I'm not the only one. Many people have done just the same and got exactly the same results. It really does work, and it really doesn't matter what you believe about the nature of the universe. If you look, this is what you'll find, but even if you don't look this is still how thing are!

(See also Seriously, The Laws Underlying The Physics of Everyday Life Really Are Completely Understood).I don't think anyone who has not done chemistry, had the practical insights into chemistry, at this level or beyond, can really understand what it's like.

~~oOo~~

Here is another account of water with prettier pictures: water.

.jpeg)