|

| Where does blue begin and end? |

Colour words do not correspond to objects or entities. Colours are broadly defined categories of perception. Categories are mental and linguistic structures that help us to organise how we perceive the world. We can use the category name to talk about all the members of a category at once without having to use tedious lists of inclusions and exclusions. This is usually possible because we interact with all members of a category in the same way.

In George Lakoff's powerful model of thinking about categories we define categories towards the middle of a taxonomical hierarchy and by relationship to a prototype. So dog seems like a "natural" category, whereas for every day use: mammal is too broad and includes too many non-dog examples that need to be excluded; while spaniel is too narrow because it leaves out too many dog examples like terrier. Dog as a category works because there are consistent ways that we interact with dogs that are common to all dogs and different from other common pets or wild animals. And also because this interaction is not something personal, but common to other people in our language group. Sometimes pet is a more convenient category: when renting out a house for example. Though we think of categories defined by forms or functions, one of the most important defining properties is how we interact either in fact or potentially with the entities.

When we think of 'dog' as a category we will have an internalised prototype that defines the category. And we judge other entities to be a member of our category to the extent that they resemble our prototype (this is an extension of Wittgenstein's family resemblances'). By definition some members may be more central and others more peripheral. Say our prototype is something like a German shepherd (left). we can acknowledge, as dogs themselves usually do, that both a chihuahua and a great dane are members of the category dog, despite their size. Similarly though a long muzzle is typical, we can acknowledge that dogs with mutated skulls that give them a squashed look (boxers, pugs) are still dogs. On the other hand despite being furry, carnivorous, quadrupeds, no kind of cat is is a member of the category dog. In Cambridge there is a couple who take their cat out on a lead. But even a cat on a lead is not a dog.

However, the prototype is not fixed or absolute. It is relative to many things, not least of which is how we interact with the category. With respect to dogs, a farmer or a hunter may think in terms of a working animal, a pet owner in terms of companionship, and so on. On the other hand in India dogs are often semi-domesticated urban scavengers - neither pets nor workers, but barely tolerable vermin. In some cultures dogs are seen as food.

However, the prototype is not fixed or absolute. It is relative to many things, not least of which is how we interact with the category. With respect to dogs, a farmer or a hunter may think in terms of a working animal, a pet owner in terms of companionship, and so on. On the other hand in India dogs are often semi-domesticated urban scavengers - neither pets nor workers, but barely tolerable vermin. In some cultures dogs are seen as food.

It's possible for there to be doubt about membership at the periphery. Is a wolf a member of the dog category? Is a fox? The wild dog is another peripheral case: it looks like a dog, but we interact with it as a wild animal (to which category it belongs with wolf and fox) rather than as pet or worker. There is no upper or lower limit on how many categories we employ or the extent to which they overlap.

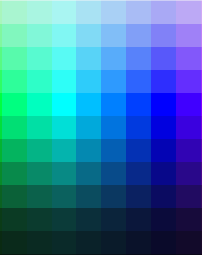

navy

royal

cobalt

azure

sapphire

beryl

electric

sky

turquoise

cerulean

teal

cyan

Our terms for colours are categories also. Typically for an English speaker the prototype for blue is the sky. This can get complicated because in England the sky is more often grey than blue, and when it is blue, it's often a very pale and washed out blue compared to where I grew up (about 15 degrees of latitude closer to the equator, about 1000ft above sea level, and with much less pollution). In some cultures lapis lazuli or the throat of a peacock are prototypes (the latter is important in India for example).

Other languages, including many living languages define their categories differently. And research has shown patterns in how languages categorise colours. Many languages for example put blue and green in one category. In ancient Chinese the word 青 qīng meant both blue and green, but also black. In this sense it appears to be similar to the Sanskrit śyāma which can mean black, dark, dark shades of blue or green. Used of people it refers to a dark complexion. So in fact, Śyāma Tārā is not Green Tārā, but Dark or Swarthy Tārā despite the fact that she is routinely depicted in bright hues.

Does this mean that those languages which lump blue in with other colours lack a concept of blue? Not necessarily. Because even blue is a broad category. I can distinguish many shades of blue, from cyan to navy, but I don't have words for all these colours. Similarly I can distinguish many shades of green from the almost yellow green of new spring leaves, to the dark blue-green of New Zealand jade. Think about all the distinctions of colours on a typical paint sampler that we have no words for, but for which arbitrary names have to be invented for marketing purposes. We also have at least one word for a colour that is made up, indigo. When Newton was describing the colours of the rainbows he created with prisms he wanted their to be seven colours to fit in with an alchemical scheme and so invented the colour indigo. What Newton called blue is what today we'd call cyan, and what he called indigo is deep blue like ultramarine or cobalt blue. In fact most English speakers shown swatches of these colours would call them both blue.

Other languages, including many living languages define their categories differently. And research has shown patterns in how languages categorise colours. Many languages for example put blue and green in one category. In ancient Chinese the word 青 qīng meant both blue and green, but also black. In this sense it appears to be similar to the Sanskrit śyāma which can mean black, dark, dark shades of blue or green. Used of people it refers to a dark complexion. So in fact, Śyāma Tārā is not Green Tārā, but Dark or Swarthy Tārā despite the fact that she is routinely depicted in bright hues.

Does this mean that those languages which lump blue in with other colours lack a concept of blue? Not necessarily. Because even blue is a broad category. I can distinguish many shades of blue, from cyan to navy, but I don't have words for all these colours. Similarly I can distinguish many shades of green from the almost yellow green of new spring leaves, to the dark blue-green of New Zealand jade. Think about all the distinctions of colours on a typical paint sampler that we have no words for, but for which arbitrary names have to be invented for marketing purposes. We also have at least one word for a colour that is made up, indigo. When Newton was describing the colours of the rainbows he created with prisms he wanted their to be seven colours to fit in with an alchemical scheme and so invented the colour indigo. What Newton called blue is what today we'd call cyan, and what he called indigo is deep blue like ultramarine or cobalt blue. In fact most English speakers shown swatches of these colours would call them both blue.

As Lakoff explains in his book on categorisation, Women, Fire and Dangerous Things, those languages that have four colour terms will have black, white, red and one of either yellow, blue or green (p.25). Now it seems that Ancient Greek was a four colour language.

"Empedocles, one of the earliest Ancient Greek color theorists, described color as falling into four areas, light or white, black or dark, red and yellow; Xenophanes described the rainbow as having three bands of color: purple, green/yellow, and red." (Ancient Greek Color Vision)

This fits the pattern noticed by colour perception research. The Greeks used four colour terms, roughly, white, black, red and yellow. So when Homer uses the phrase "wine dark sea" or describes the sky as "bronze", he is employing categories that are much broader than we currently use in English. In fact modern English has eleven basic colour categories:

"black, white, red, yellow, green, blue, brown, purple, pink, orange and gray."

This does not stop us seeing blueish green, yellowish red, reddish purple and other colours for which we have no name or category. Categories are as broad as are useful to us. And often colours are difficult to categorise. Blue-green colours for example may appear to be in different categories to different people. But there is no evidence to suggest any anatomical differences between speakers of languages with four or less colour terms and those with eleven.

Now colour perception is a feature of our particular sensory apparatus. We've seen recently with the example of "that dress" how the background against which we see something and the colour of the light illuminating it, affect how we perceive it. But vision does have an objective component because the physiology of it is the same for everyone. Light of particular wavelengths hits our retina and activates patterns of the three (sometimes four) kinds of colour sensing cone cells. Each of the cells responds to different frequencies of light.

The peaks of these curves are the same in all humans. This means that where languages have the same colour terms they tend to agree on where in the spectrum the prototype for that category lies. I presume this has applied at least since anatomically modern humans. Now of course turning the signals from our cone cells into the experience of colour is a process that happens in our brains. But it's not arbitrary. For people who are not colour blind the brain is set up for blue cone cells to respond to the same frequency of light. If I shine light with a frequency of 500 nm in your eyes, you'll perceive this in more or less the same way as every other human being regardless of language and culture. Linking the experience to a word is a function of language, but the ability of the language to translate the experience into words is always limited. People with four cones describe a far more vivid palette of colours (What it's like to see 100 times the colors you see). Some animals have cones sensitive to different wavelengths. In particular bees can see much shorter wavelengths - well into what we call the ultraviolet. While snakes can detect much longer wavelengths in the infrared (though not with their eyes)

Now, the story goes that because some languages lack a word that corresponds to the English word blue, and they treat what we call blue as a member of broader colour category, that this means that the speakers of that language could not see blue. This is like saying that because the English lack a word for schadenfreude that they do not enjoy the misfortunes of others, whereas in fact the laughing at the misfortunes of others is very popular here (it is perhaps the most important theme of English humour). So why does this suggestion keep surfacing?

The idea about the Greeks not being able to see blue can be traced to the 19th century British Prime Minister and amateur philologist William Gladstone. He published a long and highly regarded study of Homer's epics and noticed that Homer's colours did not match ours, the "wine-dark sea" being one of the well known examples (wine being reddish-purple in our language, a colour we never associate with the sea). Others joined in. More recently the idea that how we use language reflects how we perceive the world is called Linguistic Relativism. It is also known as the Whorf-Sapir Hypothesis because theories about it were postulated (separately) in the early 20th Century by linguistic Benjamin Lee Whorf and his teacher Edward Sapir (amongst others). Whorf in particular was interested in the way that grammar divided the world up into entities and activities. He discovered that some Indigenous American languages seem to not make the same kinds of distinctions. On the basis of this he hypothesised that these differences in grammar might affect how we see the world at a very deep level. How would the world appear to us, for example, if we did not divide it up into nouns and verbs. What if we only had verbs for example, if everything was seen as a process? Whorf asked is the world really is divided up into objects

Linguistic relativism comes and goes in the media. Every few years some journalist comes across Whorf or some other author and writes a piece about it. I should add that Whorf's essays make very good reading (they were collected into a book, Language, Thought and Reality, MIT Press, 1956). The "Greeks couldn't see blue" meme is a popular version of this and one can find many variations on the theme, on the internet, including a few other attempts to debunk it.

The idea about the Greeks not being able to see blue can be traced to the 19th century British Prime Minister and amateur philologist William Gladstone. He published a long and highly regarded study of Homer's epics and noticed that Homer's colours did not match ours, the "wine-dark sea" being one of the well known examples (wine being reddish-purple in our language, a colour we never associate with the sea). Others joined in. More recently the idea that how we use language reflects how we perceive the world is called Linguistic Relativism. It is also known as the Whorf-Sapir Hypothesis because theories about it were postulated (separately) in the early 20th Century by linguistic Benjamin Lee Whorf and his teacher Edward Sapir (amongst others). Whorf in particular was interested in the way that grammar divided the world up into entities and activities. He discovered that some Indigenous American languages seem to not make the same kinds of distinctions. On the basis of this he hypothesised that these differences in grammar might affect how we see the world at a very deep level. How would the world appear to us, for example, if we did not divide it up into nouns and verbs. What if we only had verbs for example, if everything was seen as a process? Whorf asked is the world really is divided up into objects

Linguistic relativism comes and goes in the media. Every few years some journalist comes across Whorf or some other author and writes a piece about it. I should add that Whorf's essays make very good reading (they were collected into a book, Language, Thought and Reality, MIT Press, 1956). The "Greeks couldn't see blue" meme is a popular version of this and one can find many variations on the theme, on the internet, including a few other attempts to debunk it.

However, quite a bit of research has shown that because of the physical apparatus of seeing there is no room for relativistic effects in colour perception. All humans see colour in the same way, even though different languages categorise colours in different ways. Every (normally sighted) human being is capable of seeing millions of colours, most of which we don't have names for (which is where categories come in handy). And all this commonality is true of subsets with variations on the the normal pattern: people with four cones see similarly to each other; people who are red-green colour blind all see the same shades of grey and so on. In other words the research disproves idea that having no word for blue means one cannot see the colour blue. So basically the whole "can't see blue" thing comes down to a failure to read the research on colour vision.

Ironically if you do a simple image search on "Greece" the predominant colours in the results are white and blue, the colours of the modern Greek flag.

Ironically if you do a simple image search on "Greece" the predominant colours in the results are white and blue, the colours of the modern Greek flag.

~~oOo~~

12 Apr 2015. See also: 3-D Map Shows the Colors You See But Can’t Name. Wired.

16 Feb 2016. See also, Bogushevskaya, Victoria. (2015). Qīng (青) in Chinese: when and why it means ‘green’, ‘blue’ or ‘dark’/‘black’, in Thinking Colours Perception, Translation and Representation [Edited by Victoria Bogushevskaya and Elisabetta Colla]. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 26-44.

28 Mar 2017. 'Why don't Americans have a name for the color 'light blue?' Study finds unique color terms used in Japan, US.' Phys.org.

10 Sept 2025. "Large-scale color biases in the retinotopic functional architecture are region specific and shared across human brains." Journal of Neuroscience. 8 September. e2717202025; . https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2717-20.2025.

See also Kavanagh, Katie. (2025). "My blue is your blue: different people’s brains process colours in the same way. A machine-learning tool can predict what colour a person is looking at when trained on the brain activity of others." Nature Articles.