My Pāḷi reading group is starting off this year by looking at the

Cūḷasuññatasutta (MN 121). There's quite a lot of commentary on this text, a number of translations and commentaries, but even before we began to read the text we discovered a quandary in the word

asuññataṃ, which only occurs in this

sutta. Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi (2001) translate the word as "non-voidness" but I don't think this makes sense.

As analogues of the Sanskrit adjective

śūnya (empty) and the abstract noun from it

śūnyatā (emptiness), we find the Pāḷi

suñña and

suññatā. However in addition, and in the title of the text no less, we find another Pāḷi form

suññato or

suññataṃ, which is not found in Sanskrit dictionaries, though some counterparts are found in Sanskrit Buddhist texts. This form is often glossed over in translations as "emptiness", presumably because it is so similar to the abstract noun that the translators don't notice the difference.

I begin writing this, it is not at all clear to me how

asuññataṃ derives and how to translate it. In this essay I will survey the uses of the term

suññato and try to establish how it ought to be translated in order to shed light on the word

asuññataṃ. My sources are the Pāḷi

Nikāyas and

Aṭṭhakathās (or commentaries), the counterparts of the

Cūḷasuññata preserved in Chinese《小空經》(MĀ 190) and Tibetan མདོ་ཆེན་པོ་སྟོང་པ་ཉིད་ཅེས་བྱ་བ། (D.291), plus a few Sanskrit fragments.

The Cūḷasuññatasutta

The passage that alerted us to this problem comes early on in the text. In Pāli it goes:

Seyyathāpi, ānanda, ayaṃ migāramāt-upāsādo suñño hatthigavassa-vaḷavena, suñño jātarūpa-rajatena, suñño itthipurisa-sannipātena atthi c'ev'idaṃ asuññataṃ yadidaṃ – bhikkhusaṅghaṃ paṭicca ekattaṃ

Before attempting to translate this, let me break procedure by giving the gist of what it says. This is the first part of an analogy designed to illustrate a procedure for gradually emptying the mind of sense impressions and thoughts with the goal of attaining the suññatāsamādhi "integration of emptiness" or suññatāvihāra "abode of emptiness". These seem to be equivalent to saññāvedayitanirodhasamāpatti or "the attainment of the cessation of perceptions and sensations" and thus also with nibbāna. This very important and interesting state I describe as "consciousness without content". One is alive and aware, but there is no content to one's experience. The ancients had no concept of a resting state network in the brain, so they struggled to make sense of this state. I imagine, for example, that something similar gave rise to the Vedic idea that Brahman could described as saccidānanda or being (sat), consciousness (cit) and bliss (ānanda). Dwelling in the state of emptiness one experiences only being, consciousness and bliss. Those who write about this state tend to assert that it does get any better than this.

In this illustration of the process, the Buddha and Ānanda are sitting having a discussion in a palace or perhaps on a terrace (

upāsāda), in the eastern part of Sāvathī (which places it near the river that formed the eastern boundary of the old city). This palace formerly belonged to someone who is almost always known as Migāra's Mother (

migāramātā). Her name was Visākhā and she was actually Migāra's wife (that story is outlined in the

DOPN). In any case it appears that the palace is given over to the

bhikkhusaṅgha for their use.

The Buddha points out that the things one would normally find in such a place, i.e. livestock, wealth, and people etc., are absent, but instead only the the bhikkhusaṅgha is present. Buddhaghosa points out in his commentary that this refers to the bhikkhus as a corporate entity, not to the individual bhikkhus. This example of the palace and the bhikkhus is an analogy for the ascetic meditating in the wilderness (arañña). The ascetic notices that their mind is empty of the sights and sounds of the village and its inhabitants, and all that is present is perceptions of the wilderness which have a sort of uniformity. The perturbations of the mind caused by village life are absent, and only the perturbations due to the wilderness are present.

The question is, how do we translate asuññataṃ and ekattaṃ? Some comments on how to translate ekattaṃ can be found in Schmithausen (1981: 233-4, n. 122). I concur with Schmithausen's argument for treating ekattaṃ not as Sanskrit ekatvā "oneness, unity", but as ekātman "having a single nature" or "uniform". Buddhaghosa seems also to agree with Schmithausen at MNA 4.151 in his gloss on bhikkhusaṅghaṃ paṭiccāti. In fact I take it to be an adverbial neuter. This essay will focus on asuññataṃ beginning by looking at the apparent source, suññato.

Suññato

PED offers the following definition:

Suññata (adj.) [i. e. the abl. suññato used as adj. nom.] void, empty, devoid of lusts, evil dispositions, and karma, but especially of soul, ego.

Here "adj. nom." means "an adjective in the nominative". The -to suffix is one way to indicate the ablative case. PED argues that suññato is an ablative of suñña (empty) that has been treated as a masculine noun and declined accordingly. This would make asuññataṃ an adjective in the accusative, going presumably with bhikkhusaṅghaṃ, and/or ekattaṃ.

Also PED sv. suñña defines the word in its neuter form suññaṃ "abl. ˚to from the point of view of the 'Empty'". Suggesting that suññato can still have an ablative sense mean "from the point of view of someone dwelling in emptiness". As we will see below this is apparent in some contexts as the word usually occurs with a verb of seeing.

The primary sense of the ablative is from where or when an action proceeds, sabbato āgacchanti "they came from all sides"; pāsādā oloketi "he looks out from the palace". Very often this relationship is conveyed in English with the preposition from. In the precepts we abstain from certain types of action, and the actions are in the ablative case, i.e. pisunāya vācāya veramanī "abstaining from speech which is slanderous". The concept of separation (as in "apart from") is also conveyed by the ablative case. It is also used to indicate cause or reason for an action, e.g. sīlato naṃ pasaṃsanti "they praise him for his virtue". And just to complicate matters the cases are somewhat flexible in Middle-Indic languages, so the ablative sometimes merges with and can be used to convey an instrumental sense (with, by, through).

But why is an ablative treated as a nominative? In order to try to understand how this might have come about let us begin with a survey the use of suññato in the Nikāyas. It doesn't occur that often, so we can be comprehensive.

Occurrences in the Nikāyas

DN iii.219 Aparepi tayo samādhī – suññato samādhi, animitto samādhi, appaṇihito samādhi.

Furthermore there are three samādhis: empty samādhi, signless samādhi and desireless samādhi.

This is from the Sangīti Sutta (DN 33) which is a long list of numerical lists. Walsh (486) translates suññato samādhi as "concentration on emptiness" (i.e. he appears to ignore the case endings). Now the three words here—suññato, animitto, appaṇihito—all appear to be the same form so we can usefully look at the other two to see if they shed light on the derivation. The etymology of nimitta is given by PED as uncertain, though possibly related to √mā 'measure'; but PED also tells us that the gender is neuter. Sv. nimitta in BHSD it is also neuter. But if nimitta is neuter then it should not form a nominative singular in -o, but in -aṃ. Is nimitto therefore another ablative in -to, possible from nimita (past participle) from ni√mā? I'm not sure.

If suññato and nimitto are ablatives then suññato samādhi might be "the samādhi [that comes] from [being] empty". Which is admittedly awkward.

By contrast paṇihita is very clearly a past participle from paṇidahati (pa+ni√dhā) "to put forth, put down to, apply, direct, intend; aspire to, long for, pray for." We can understand apaṇihita as a bahuvrīhi, "without longing", as opposed to a karmadhāraya "undesired". Unfortunately this breaks up the pattern. So it looks like each word, though superficially similar, might derive the -to ending via a different route.

A variation on this occurs at SN iv.360 in the

Suññatasamādhi Sutta (SN 43:4):

Katamo ca, bhikkhave, asaṅkhatagāmimaggo? Suññato samādhi, animitto samādhi, appaṇihito samādhi.

And what, bhikkhus, is the path leading to the unconditioned? The empty samādhi, signless samādhi and desireless samādhi.

Here Bodhi (2000: 1373) translated suññato as "emptiness", i.e. as though he is translating the abstract noun suññatā. However, the feminine noun suññatā cannot take an -o ending, so something is wrong with this.

MN i.302 "Saññāvedayitanirodhasamāpattiyā vuṭṭhitaṃ panāyye, bhikkhuṃ kati phassā phusantī" ti? "Saññāvedayitanirodhasamāpattiyā vuṭṭhitaṃ kho, āvuso visākha, bhikkhuṃ tayo phassā phusanti – suññato phasso, animitto phasso, appaṇihito phasso"ti.

However, lady, rousing from the attainment of cessation of perceptions and sensations what feelings do those bhikkhus come into contact with? Friend Visākha, those bhikkhus come into contact with three sensations on rousing from the attainment of cessation of perception and experience, namely contact from/with that which is empty, contact from/with that which is signless, and contact from/with that which is desireless.

This is from a discussion between Dhammadinā and her former husband, Visākha, in the Cūḷavedalla Sutta (MN 44). This is a very interesting passage about going into and emerging from cessation and the way that experience fades out and in. The question is literally "What contacts do they contact?" Phasso is in the masculine nominative singular. Here suññato as ablative case, perhaps overlapping with the instrumental may make sense and I've hedge my translation to indicate this. Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi again translate suññato as the abstract "voidness" (2001: 400). This passage recurs at SN iv.294 where suññato is translated by Bodhi as "emptiness"

MN i.435. So yadeva tattha hoti rūpagataṃ vedanāgataṃ saññāgataṃ saṅkhāragataṃ viññāṇagataṃ te dhamme aniccato dukkhato rogato gaṇḍato sallato aghato ābādhato parato palokato suññato anattato samanupassati.

One regards as impermanent, disappointing, a disease, a tumour, an arrow, a calamity, an affliction, as other, as disintegrating, as empty (suññato), and as unsubstantial anything that is connected with form (rūpagata), sensations, perceptions, volitions, and cognitions.

The ways that one should regard dhammas are all ablatives in -to. And the context suggests we read them as meaning "as". So that te dhamme suññato samanupassati should mean "he regards those dhammas as empty". Here suññato cannot be construed as the abstract "emptiness". An important point here is that the cognitive action is taking place in a state of jhāna.

Perhaps here we can take te dhamme aniccato samanupassati to mean "he regards these dhammas from the point of view of impermanence"? We might argue, for example, that if anicca was an adjective here, then it would take the plural, annice, to go with the noun dhamme in the plural. Therefore aniccato which is singular is not an adjective and is not describing the dhammas, but is indicating from whence the verb of seeing proceeds. Thus this could be see as an example of suññato having an ablative sense.

This passage is reflected in the Saṃyutta Nikāya. At SN iii.167 the question is asked to what dhammas a virtuous monk should pay attention. The answer is:

Sīlavatā... bhikkhunā pañcupādānakkhandhā aniccato... suññato yoniso manasi kātabbā.

A virtuous monk should pay attention to the five underlying apparatus of experience as impermanent... as empty... etc.

Again Bodhi reads the text as saying that the

khandhas should be seen

as impermanent...

as "empty" (2000: 970). Here the word

pañcupādānakkhandhā is a nominative plural and Bodhi is tacitly reading

aniccato as a nominative singular and the sentence as a simple apposition. Note that here also the verb is one in which one regards or pays attention to the

khandhas. Buddhaghosa glosses

sattasuññataṭṭhena suññato (SNA 2.333) i.e. "with the meaning of 'empty of a being'".

There is a Sanskrit fragment that parallels this (Thanks to Dhīvan for pointing this out to me):

(ani)tyataḥ duḥkhataḥ śunyataḥ anāt[m]ato manasikarttavyāḥ. (Anālayo 2013: 11)

[Something]... should be attended to as empty etc.

This passage recurs at AN ii.128 and AN iv.423, where is is again associated with the cultivation of

jhāna and AN ii.129 associated with the

brahmavihāras. Here the one who does these practices has a pleasant rebirth that is not shared with worldings (

Ayaṃ, bhikkhave, upapatti asādhāraṇā puthujjanehi.).

Finally the word occurs in the

Suttanipata Sn 1119 (mentioned in the PED definition of

suñña):

"Suññato lokaṃ avekkhassu, mogharāja sadā sato;

Attānudiṭṭhiṃ ūhacca, evaṃ maccutaro siyā;

Evaṃ lokaṃ avekkhantaṃ, maccurājā na passatī" ti.

View the world as empty, Mogharāja, always mindful;

Having destroyed self-vew, one may cross over death;

The King of Death does not see the one who views the world this way.

(My translation more or less follows K.R Norman here).

Norman was the leading authority on Middle-Indic languages and particularly in his translation of the Suttanipata paid close attention to the meaning of every word. So the fact that he reads suññato lokaṃ as "the world as empty" is significant. However, he does not discuss this choice in detail in his notes, but instead refers readers to E.J. Thomas (1951: 218) who simply says that suññata is an adjective meaning "void". Note that here lokaṃ is an accusative singular and the verb once again involves seeing. Here, as above, I'm inclined to take the ablative as representing a point of view. To me this suggests seeing the world from the point of view of the suññatavihāra (as in the PED definition cited above).

So the modern translators seem undecided on how to translate suññato. Depending on unknown factors, since it is never discussed, suññato can represent the abstract (though the morphology is all wrong for this) and be translated as "voidness, emptiness"; or it can represent the adjective and be translated as "void, empty", sometimes with the sense of "as empty". In combination with verbs of seeing it can be thought of as "from the empty point of view". In order to understand how ancient Theravāda commentators might have understood the word we can look at the glosses in the Aṭṭhakathās.

Commentarial glosses

DNA 3.1003. Maggasamādhi pana rāgādīhi suññatattā suññato, rāganimittādīnaṃ abhāvā animitto, rāgapaṇidhiādīnaṃ abhāvā appaṇihito ti

However the samādhi of the path is empty (suññato) because of the emptiness (suññatattā) of passion etc, is signless from the nonexistence of signs of passion etc, is desireless from the nonexistence of desire for passion etc.

Here the abstract noun suññatatta (suññatattā is the ablative of cause) is telling. It points quite strongly to Buddhaghosa constructing this sentence with suññato meaning "empty". The samādhi under discussion lacks rāga, dosa, and moha or attraction, aversion, and confusion and lacking these is said to be empty (suññato) giving it the quality of emptiness (suññatatta).

MNA 2.366/ SNA 3.97 suññato phassotiādayo saguṇenāpi ārammaṇenāpi kathetabbā. saguṇena tāva suññatā nāma phalasamāpatti, tāya sahajātaṃ phassaṃ sandhāya suññato phassoti vuttaṃ. animittāpaṇihitesupieseva nayo. Ārammaṇena pana nibbānaṃ rāgādīhi suññattā suññaṃ nāma, rāganimittādīnaṃ abhāvā animittaṃ, rāgadosamohappaṇidhīnaṃ abhāvā appaṇihitaṃ. Suññataṃ nibbānaṃ ārammaṇaṃ katvā uppannaphalasamāpattiyaṃ phasso suññato nāma. animittāpaṇihitesupi eseva nayo.

Taking up the phrase "empty contact" (suññato phasso), it should be explained according its own qualities (saguṇena) and according to its basis (ārammaṇa). According to its own qualities, it is the attainment of the fruit called “emptiness” (suññatā). Coinciding with that [emptiness], contact with reference to it, is called “contact that is empty”. Animitta and apaṇihita are inferred in the same way.

However, according to its basis, nibbāna is named “empty” (suññaṃ), because of emptiness of attraction (rāga) etc; [named] signless because of the absence of signs of attraction etc, and desireless because of the absence of desire for attraction, aversion, and ignorance. Having made a case that nibbāna is emptiness, the attainment of the arisen fruit is called "contact that is empty". Animitta and apaṇihita are inferred in the same way.

This section of commentary is looking at MN i.302 mentioned above. The subject is what someone who has attained the cessation of perceptions and sensations comes into contact with when they rouse themselves (vuṭṭhitaṃ) from the attainment. For them contact is empty or absent. In Buddhaghosa's view their attainment is nibbāna and they don't experience the world the way ordinary people do any more. Contact for them is empty, signless and desireless. Here Buddhaghosa uses suñña and suññato synonymously and suññatā as a synonym for nibbāna. Again we see words like suññato and suññatā being used to indicate absence.

A short gloss is found at MNA 3.146: nissattaṭṭhena suññato "with the meaning without a being (nissatta)." Another as ANA 2.334 sattasuññataṭṭhena suññato, "with the meaning of emptiness of a being", confirming that nissatta should be read as "without a being" rather than with PED "powerless". The sense here is that empty means the absence of a being (satta).

Buddhaghosa, then, is more consistent in treating

suññato as synonymous with

suñño, and both as meaning "empty of [something]" or that the object is absent.

Sanskrit Udānavarga

We've seen one fragment that uses the Sanskrit equivalent of suññato, i.e. śunyataḥ. Skilling (1981: 226) gives a more substantial example. He notices that in the Udānavarga (a Dharmapada text) there is a series of verses that are counterparts to the Pāli Dhammapada vs 277-279, whence the well known triplet sabbe saṅkhārā aniccā, sabbe saṅkhārā dukkhā, and sabbe dhammā anattā. Compare the Udānavarga (Uv 12. 5-8; first lines only)

anityāṃ sarvasaṃskārāṃ prajñayā paśyate yadā... [5]

duḥkhāṃ sarvasaṃskārāṃ prajñayā paśyate yadā... [6]

śunyataḥ sarvasaṃskārāṃ prajñayā paśyate yadā... [7]

sarvadharmā anātmānaḥ prajñayā paśyate yadā... [8]|

When he sees with insight all constructs as impermanent...

When he sees with insight all constructs as disappointing...

When he sees with insight all constructs as empty...

When he sees with insight all experiences as insubstantial...

Compare the Dhp 277 where the first line is

sabbe saṅkhārā aniccā ti yadā paññāya passati. Here "that which is seen" is given as a nominal sentence followed by the quotative particle. In Pāḷi

sabba is a separate word, declined as a pronoun (nominative plural), whereas in Sanskrit

sarva is undeclined and compounded with the noun it qualifies, though there is no change in meaning in this difference. In the Uv 12.5 and Uv 12.6, what is seen with insight, e.g.

anityāṃ sarvasaṃskārāṃ, is in the accusative plural, making it the patient of the verb of seeing. Note that word order is not important here, so the fact that the two parts of the apposition, e.g.

anityām and

sarvasaṃskārāṃ are not the same order as in Pāḷi, i.e.

saṅkhārā and

aniccā is not significant. As Dhīvan pointed out in an email, in Bernard's edition of the

Udānavarga on

Sutta Central, Uv 12.6 begins

duḥkhaṃ hi sarvasaṃskārāṃ with

duḥkha in the singular. Dhīvan suggests that we treat this as nominal, as in the Pāḷi, "When one sees with wisdom all constructions indeed are disappointing...". However

saṃskāra is masculine and the

-āṃ ending is unequivocally accusative plural. So perhaps "When one sees with insight all the constructions that are indeed disappointing..."?

Now in Uv 12.7 the Sanskrit word is śunyataḥ (with śūnyataḥ given as an alternate reading) = Pāḷi suññato. One way to explain the short u might be that this is a loan word from Middle Indic which has not been fully assimilated to Sanskrit morphology rules that demand a long ū i.e. śūnyataḥ. Despite grammatical problems with Uv 12.8 (see below) the general outline here seems to be that all constructs are identified with a series of qualities, particularly: impermanence, disappointment, and insubstantiality. So we expect 12.7 to fit this pattern. We expect śunyataḥ to be just like the other adjectives: anitya, duḥkha, anātman. But it isn't. Whichever case we take śunyataḥ to be, (ablative and nominative are possible) it simply does not fit the pattern because it is singular and the noun it is describing is plural (though cf. the Bernard Ed. of Uv 12.6 which is singular). Adjectives take the case, number and gender of the noun they describe; predicates have to at least be in the same case. To qualify sarvasaṃskārāṃ we expect śunyataṃ. It appears that something has gone wrong in adding this line to the text.

Lastly in 12.8 the grammar is mangled. Perhaps echoing the Middle-Indic syntax, here sarvadharmā anātmānaḥ are in the nominative plural (matching the Pāḷi equivalent sabbe dhammā anattā ti). In Sanskrit grammar this would make them the agents of the verb, which would be nonsense. Pāḷi avoids this by adding the quotative particle. The correct grammar, matching 12.5,6 would be sarvadharmāṃ anātmanaḥ. This error might be scribal - a missing anusvāra and an incorrectly lengthened vowel are certainly common scribal errors, but that they would make the exact mistakes in two consecutive words that would accurately change them to be the same (wrong) case seems unlikely.

Unfortunately this Sanskrit example does nothing to clarify the situation. Nor does Skilling add any comment on this point, indeed he talks as if the text has śūnyatā instead. The grammatical mistake in 12.8 makes us doubt the text. But clearly the person who added the verse at Uv 12.7 understood the sentence to be the same form as 12.5,6 and likely 12.8 as well (error notwithstanding). The only way I can see to make sense of this is to treat śūnyataḥ as indeclinable. It does not change case to match the noun because it cannot. But this is far from satisfactory because it conflicts with what we already know.

Having more or less exhausted the relevant Indic language sources, we can now turn to the versions of the

Cūḷasuññata Sutta preserved in Chinese and Tibetan.

The Chinese Text

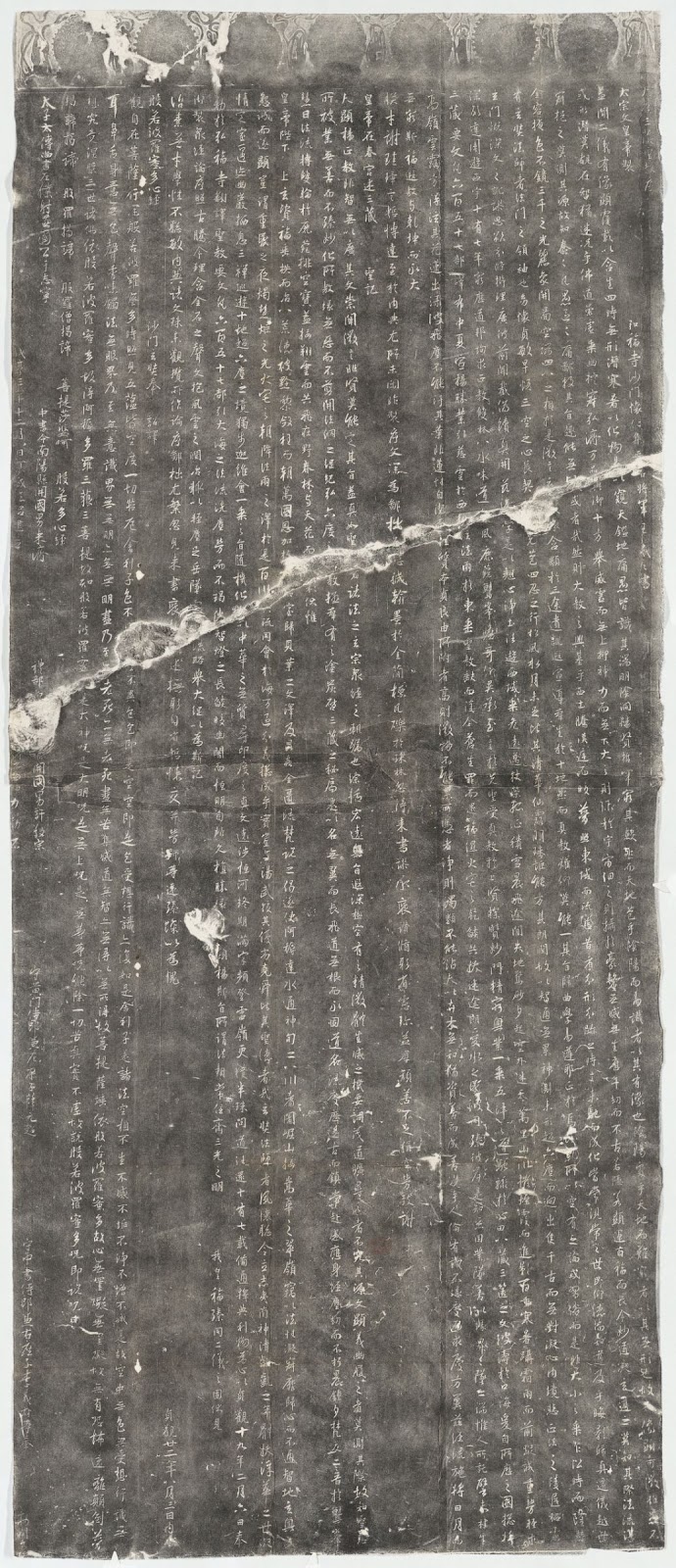

The Cūlasuññata Sutta has a counterpart in the Chinese Madhyamāgama, i.e. MĀ 190 《小空經》 The Lesser Emptiness Sūtra. The parallel passage in Chinese is:

阿難!如此鹿子母堂,空無象、馬、牛、羊、財物、穀米、奴婢,然有不空,唯比丘眾。(T1 737a9-10)

Ānanda, 阿難 it is like 如此 this palace 堂 of Migara’s 鹿子 mother 母,is empty 空無 of elephants 象、horses 馬、cattle 牛、sheep 羊、money 財物、rice grain 穀米、male and female slaves 奴婢,however 然 it is 有 non-empty 不空,of only 唯 the bhikṣu-saṃgha 比丘眾

The character for both empty and emptiness is 空, however we also see here the use of 空無 which can also just mean "empty, emptiness", but which might also mean "empty and without". Where our Pāli text has asuññataṃ the Chinese has 不空 which we would expect to mean "non-emptiness" and reflect Sanskrit aśūnyatā. But the lack of clear information on inflexions in Chinese leaves considerable room for doubt. Skilling notes that the Chinese and Tibetan versions are closer to each other than either is to the Pāḷi, so next (with a little help from my friends) we can now look at the last source on the list, the Tibetan version of the Cūḷasuññata Sutta.

The Tibetan Text

Amongst the very few Tibetan translations of Nikāya/Āgama texts are the two Śūnyatā texts (Skilling 1994, 1997; also

Degé vol. 71: 250a.1-253b.2). My thanks to Joy Vriens and Maitiu O'Ceileachair for help with understanding the Tibetan. The parallel passage in the Tibetan is (though see Skilling 1994 critical edition for variant readings):

kun dga' bo 'di lta ste | dper na ri-dags 'dzin gyi ma'i khaṅ bzaṅ 'di glaṅ-po-che daṅ | rta daṅ | ba laṅ daṅ | lug daṅ | bya gag daṅ | phag gis stoṅ ziṅ nor daṅ | 'bru daṅ | 'gron bu daṅ | gser gyis stoṅ la | bran daṅ | bran mo daṅ | las byed pa daṅ | zo śas 'tsho ba dag daṅ | skyes pa daṅ | bud-med-daṅ | khye'u daṅ | bu mo dag gis stoṅ yaṅ 'di na 'di lta ste | dge sloṅ gi dge 'dun kho na 'am | de las kha cig la brten nas mi stoṅ pa yaṅ yod do || (Skilling 1994: 150)

Mṛgāra Mother's Mansion is empty of elephants, horses, cows, sheep, roosters, and pigs. It is empty of wealth, grain, money and gold. It is empty of man-servants and maid-servants, of workers and dependants, of men and women, of boys and girls. But with regard to one thing there is non-emptiness, that is, the community of monks alone. (Skilling 2007: 234)

Compare the translation of the last sentence found in Skilling (1997: 349) "there is still the assembly of monks, or whatever depends upon it, that is not absent".

Skilling explains, "here the Pāḷi has paṭicca ekattam, the Tibetan has kha cig la breten nas, suggesting *pratītya ekatyam, with the Buddhist Sanskrit ekatya [Pāḷi ekacca; "someone, anyone" BHSD] where one would rather expect ekatva—perhaps a wrong Sanskritisation" (1997: 349-350). This leave Skilling at a loss for a translation, but as I have already pointed out above, Schmithausen argues convincingly that Pāḷi ekattaṃ reflects Sanskrit ekātman which would I think would solve Skilling's problem. In a note (1997: 349, n.49) offers a tentative reconstruction of the Sanskrit

dge sloṅ gi dge 'dum = bhikṣusaṃgha; kho na 'am = eva vā; de las kha cig = tato ekatyaṃ; la brten nas = pratītya; mi stoṅ pa = aśūnya; yaṅ = api (ca, tu); yod do = asti.

i.e. asti ca eva [idaṃ] aśunyaṃ tato bhikṣusaṃgha pratītya ekatyaṃ.

C.f. Pāḷi atthi c'ev'idaṃ asuññataṃ yadidaṃ – bhikkhusaṅghaṃ paṭicca ekattaṃ

Despite this, the Tibetan translator has evidently read an adjective here which he translates as mi stoṅ pa suggesting that his Sanskrit text had aśūnya at this point. Seemingly the unknown Sanskrit translator understood his text to be using an adjective. Unfortunately no Sanskrit ms. of this text survives to enable cross-checking. Sanskrit aśūnya would be consistent with the Chinese 不空.

The only thing we can take from this is a stronger sense that, contra Ñāṇamoli and Bodhi (2001) the abstract of "non-voidness" sense is not intended here.

Discussion

Now I have to attempt to summarise a great deal of information that is often contradictory. Before looking at asuññataṃ we need to state again that suñña means "empty", and in this context something that is referred to as suñña is absent. So when the Buddha says to Ānanda, ayaṃ migāramātupāsādo suñño hatthigavassavaḷavena "this mansion of Migāra's Mother's is empty of elephants etc.", he means that there are no livestock present, no livestock to be seen. Contrarily if something is asuññata then we can take this to mean that something is not-absent or present.

There seem two most likely ways to arrive at the morphological form asuññataṃ. Firstly we can take suññataṃ it as an accusative singular of the abstract noun suññatā. Various translators do treat suññato as "emptiness". But as some texts point out, the word suññatā in this context really applies only to the attainment of the goal, i.e. to nibbāna. In this view asuññatā would mean something like "presence" (an abstraction from "present"). However the abstract "presence" does not quite fit the context.

Secondly we can derive suññataṃ from the ablative suññato. It seems that this word was originally combined with verbs meaning to see, i.e. √paś or consider i.e. manasi√kṛ with the sense of "as" - dhammā suññato passati "to see dhammas as empty" or "to see dhammas from the empty point of view" or a point of view that is empty of defilements or perhaps, according to Buddhaghosa, empty of a being. The word suññato was then lexicalised, that is to say it was treated as a word in its own right rather than a declined form, with the meaning "empty; absent" and treated as a nominative singular with an accusative singular in suññataṃ. (Which I admit is more or less what PED says, but now we know why it says that and that it is correct which is a bonus where the PED is concerned). The two derivations produce the same accusative singular, suññataṃ.

The etymological meaning of asuññataṃ would be "non-emptiness" or "not-empty" and as far as I know every translator has opted for something along these lines. However I suggest we can be a bit lazy about this kind of morphology in Pāli. We don't always think about what the word really means. A negated term often has a positive value and need not be slavishly translated as not-X or without-X. In this case asuññataṃ clearly refers to something present (in contrast to absent) or visible or something along these lines. To insist on using a word that preserves the Pāḷi morphology is no more sensible than preserving the Pāḷi syntax (a practice dubbed "Buddhist Hybrid English" by Theologian Paul Griffiths). I think we have to translate the word as "present" or "presence".

Coming back to the passage under consideration, the Buddha points out to Ānanda first what is absent and then what is present. What is present at the mansion are only bhikkhus, and because there are only bhikkhus they have a sort of uniformity (ekattaṃ = ekātman) when considered with respect to what one would expect to find in a mansion, including livestock, people, and wealth. As above I think we have to take ekattaṃ as an adverbial accusative.

However, as my friend Sarah has pointed out, idaṃ is a neuter pronoun. Later when asuññataṃ is replaced in the same sentence structure by the feminine noun in the nominative case darathamattā the associated pronoun changes to ayaṃ which is also feminine nominative. This suggests that the word asuññataṃ is a neuter nominative in this sentence and the only way we can think of this happening is if it is an adjective or adjectival compound that is forced to change gender to fit a noun or pronoun, i.e. a bahuvrīhi compound a-suññatā meaning "without emptiness". So, despite everything, idaṃ asuññataṃ must mean "this presence".

Thus I would argue that our sentence ought to be translated this way:

Seyyathāpi, ānanda, ayaṃ migāramāt-upāsādo suñño hatthi-gavassa-vaḷavena, suñño jātarūpa-rajatena, suñño itthipurisa-sannipātena atthi c'ev'idaṃ asuññataṃ yadidaṃ – bhikkhusaṅghaṃ paṭicca ekattaṃ; evameva kho, ānanda, bhikkhu amanasikaritvā gāma-saññaṃ, amanasikaritvā manussa-saññaṃ, arañña-saññaṃ paṭicca manasi karoti ekattaṃ.

Ānanda, just as livestock, wealth, and people are absent from this palace of Migāra's Mother and there is only this presence, uniformly dependent on the community of monks; just so, Ānanda, a monk doesn't pay attention to perception of the village, or people, but uniformly pays attention to the perception of the forest.

Note that in the last phrase

manasi karoti ekattaṃ the

ekattaṃ naturally functions as an adverb of the main verb

manasikaroti to mean "uniformly paying attention".

A few lines on, the bhikkhu who applies this practice comes to understand

Iti yañhi kho tattha na hoti tena taṃ suññaṃ samanupassati, yaṃ pana tattha avasiṭṭhaṃ hoti taṃ "santamidaṃ atthī"ti

Thus, that which is not there (tattha na hoti) he perceives that as absent (suñña); however that which remains (avasiṭṭhaṃ) is there (tattha) and he knows "there is this present" (santamidaṃ attthi).

We can see the practice as like progressively applying a set of filters on experience, so that what we are aware of is gradually diminished until we are aware of nothing, or there is just absence. It's not that the world ceases to exist, but that we narrow our

world of perception down until nothing is presenting itself to our conscious mind. Nothing disturbs the mind, nothing disturbs the deep equanimity of being in this state. And this, the texts tell us, is what

Nibbāna is like.

~~oOo~~

Anālayo. (2011). A Comparative Study of the Majjhima-nikāya. Vol. 2 (Studies of Discourses 91 to 152, Conclusion, Abbreviations, References, Appendix) https://www.buddhismuskunde.uni-hamburg.de/pdf/5-personen/analayo/compstudyvol2.pdf [II.683-8.]

Anālayo. (2013). On the Five Aggregates (2) ─ A Translation of Saṃyukta-āgama Discourses 256 to 272. Dharma Drum Journal of Buddhist Studies, 12, 1-69.

Bodhi (2000) The Connected Discourses of the Buddha. Wisdom.

Anālayo. (2015). Compassion and Emptiness in Early Buddhist Meditation. Windhorse Publications.

Choong, Mun-keat. (1999). The Notion of Emptiness in Early Buddhism. 2nd rev. ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Ñāṇamoli & Bodhi. (2001) The Middle Length Discourses. Wisdom.

Piya Tan. (2005)Cūḷa Suññata Sutta. The Lesser Discourse on Emptiness. http://dharmafarer.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/11.3-Cula-Sunnata-S-m121-piya.pdf

Satyadhana. The Shorter Discourse on Emptiness (Cūḷasuññatasutta, Majjhima-nikāya 121): translation and commentary. Western Buddhist Review. https://thebuddhistcentre.com/system/files/groups/files/satyadhana-formless_spheres.pdf

Schmithausen, Lambert. (1981) “On Some Aspects of Descriptions or Theories of ‘Liberating Insight’ and ‘Enlightenment’ in Early Buddhism”, in Studien zum Jainismus und Buddhismus,

Gedenkschrift für Ludwig Alsdorf, (Alt- und Neu-Indische Studien, 23), K. Bruhn et al. (ed.), Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner, pp. 199-250.

Skilling, Peter. (2007) Mṛgara’s Mother’s Mansion, Emptiness and the Sunyata Sutras. Journal of Indian and Tibetan Studies, 11: 225-247. http://www.jits-ryukoku.net/data/11/ick11_skilling.pdf

Skilling, Peter. (1994). Mahāsūtras: Great Discourses of the Buddha. Vol 1. Pali Text Society.

Skilling, Peter. (1997). Mahāsūtras: Great Discourses of the Buddha. Vol 2. Pali Text Society.

Thomas, E. J. The History of Buddhist Thought. Routledge And Kegan Paul Limited. Online: https://archive.org/stream/historyofbuddhis031559mbp#page/n245/mode/2up

Walshe, Maurice. (1987) The Long Discourses of the Buddha. Wisdom, 1995.