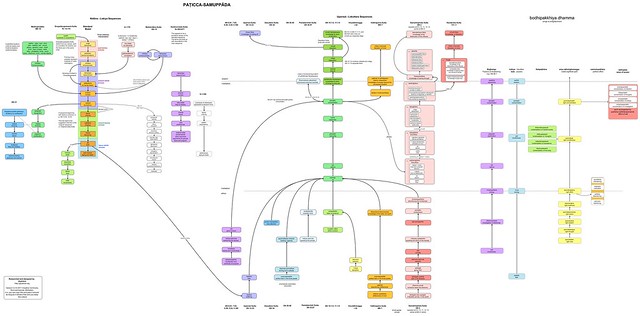

I have now identified more than two dozen texts which describe the Spiral Path. [1] Two more recently came to my attention. AN 10.61 and 10.62 are the same except that AN 10.62 adds 'craving for becoming' at the bottom of the spiral. These two texts are significantly different from all other Spiral Path texts. For one thing there is a downward spiral and an upward one, which both seem to operate on the same principle. The nodes on the path are distinctive, though reminiscent of the path outlined in the Samaññaphala Sutta (DN 2). The central sequence from pamojja to samādhi, a feature of virtually all the other Spiral variations is entirely missing. From the morality related nodes we go into a meditation phase of a different sort. The wisdom phase is collapsed into one node and does not highlight the distinction between the experience of liberation and the knowledge of liberation. What makes this a Spiral Path is the syntax, and the presence of the rain simile. Below is a condensation of the two texts combined. [2]

I have now identified more than two dozen texts which describe the Spiral Path. [1] Two more recently came to my attention. AN 10.61 and 10.62 are the same except that AN 10.62 adds 'craving for becoming' at the bottom of the spiral. These two texts are significantly different from all other Spiral Path texts. For one thing there is a downward spiral and an upward one, which both seem to operate on the same principle. The nodes on the path are distinctive, though reminiscent of the path outlined in the Samaññaphala Sutta (DN 2). The central sequence from pamojja to samādhi, a feature of virtually all the other Spiral variations is entirely missing. From the morality related nodes we go into a meditation phase of a different sort. The wisdom phase is collapsed into one node and does not highlight the distinction between the experience of liberation and the knowledge of liberation. What makes this a Spiral Path is the syntax, and the presence of the rain simile. Below is a condensation of the two texts combined. [2]Spiral path at 10.61 & 10.62

The beginning of craving-for-becoming isn’t clear. And yet craving-for-becoming has a specific condition (idappaccaya).In Pāli the terms for the second, upward path are:

Craving-for-becoming is fed, and fulfilled by ignorance,

Ignorance is fed, and fulfilled by the five hindrances,

The five hindrances are fed, and fulfilled by the three bad courses,

The three bad courses fed, and fulfilled by the non-restraint of the senses,

Non-restraint of senses is fed, and fulfilled by the unmindfulness and inattentiveness,

Unmindfulness and inattentiveness are fed, and fulfilled by unwise attention,

Unwise attention is fed, and fulfilled by lack of faith,

Lack of faith is fed, and fulfilled by not hearing the good teaching,

Not hearing the good teaching is fed and fulfilled by not associating with good people.

Association with good people feeds and fulfils hearing the true teaching,

Hearing the true teaching feeds and fulfils faith,

Faith feeds and fulfils wise attention,

Wise attention feeds and fulfils mindfulness and attentiveness,

Mindfulness and attentiveness feeds and fulfils sense restraint,

Sense restraint feeds and fulfils the three good courses,

The three good courses feed and fulfil the fours foundations of mindfulness,

The four foundations of mindfulness feed and fulfil the seven bodhi factors,

The seven bodhi factors feed and fulfil liberation through knowledge.

Just as, when the gods pour down rain over the mountains, water flows down the mountainside filling up the branches of the crevices and gullies; having filled the crevices and gullies, small lakes, and the great lakes are filled; the great lakes being filled the small rivers fill up; the small rivers fill up the large rivers, and the large rivers fill up the great ocean.

- sappurisa-saṃseva - association with good people.

- saddhammassavana - hearing the true dhamma

- saddhā -faith

- yoniso-manasikāra - wise attention

- sati-sampajañña - mindfulness and attentiveness

- indriya-saṃvara - restraint of the sense faculties

- tīṇi sucaritāni - three good courses (i.e. good actions of body, speech and mind)

- cattāro satipaṭṭhānā - four foundations of mindfulness

- satta bojjhaṅgā - seven factors of bodhi.

- vijjāvimutti - liberation through wisdom

Note that the specific condition for faith is hearing the dhamma. Faith here does not arise on the basis of practice or personal experience, but either through the intellectual understanding, the intuitive grasp of what is heard; or the charisma of the speaker. This seems to contradict the usual modern narratives about faith being based on personal experience (hence the cliché that Buddhism doesn't require blind faith). From experience, as we see in complimentary texts like AN 6.10 or AN 11.12, arises 'confirmed confidence' or 'definite clarity' (aveccapasāda) not faith. I've not seen this distinction made before, and plan to return to this theme in a future post.

In the upward spiral to the restraint of senses the nodes are very similar to other Spiral Path texts (e.g. DN2, SN 55.40, MN 7 etc). Then we have three sub-lists. The three good courses, the four foundations, and the seven bodhi-factors. This is similar to the list found in the Ānāpānasati Sutta (MN 118) where ānāpānasati fulfils (paripūri) the four foundations and seven bodhi-factors as well, and leads to vijjāvimutti. Note the use of the same verb.

The prefix in sappurisa and saddhamma is a contraction of sant (or Sanskrit sat). This is a present participle of the verb √as 'to be' (related to English is) and means 'being; true, real, actual; good'. The related word sacca (Skt. satya) is 'truth, reality'. So a sap-purisa is a true or good man, in the moral sense (a 'good' Buddhist). Similarly the sad-dhamma is the 'true or correct teaching'.

Vijjāvimutti seems like an unusual term to me. As PED notes vijjā is usually only secondary when it comes to bodhi. The opposite of avijjā is more often ñāṇa 'knowledge'. Vijjā is often associated with mundane, worldly knowledge on the one hand; and with esoteric or occult knowledge on the other. Later in tantric Buddhism vidyā is used as a synonym for mantra. Of course there are the tevijjā, the three types of knowledge which constitute the intellectual content of the Buddha's awakening, though this formulation seems to be a conscious parody of the Brahmanical triveda, the three books of sacred revelations. In his Saṃyutta translation Bodhi translates vijjāvimutti as a dvandva compound "true knowledge & liberation". The latter is justified in a note (p.1904, n68) which points to the phrase vijjā ca vimutti ca at SN 45.159 (PTS S v.52) and (PTS v.329) which says the bodhi-factors fulfil two things, i.e. vijjāvimutti. So vijjā here may well signify seeing through (vipassana) or knowledge & vision of things as they are (yathābhūta-ñāṇadassana) which results in liberation (vimutti).

Another interesting feature of these two texts is way the nodes are linked. Each sutta gives two sequences, both linked in two ways. Firstly the nodes are the food (āhāra) for next node. Secondly each node fulfils (paripūri) the next. The former, āhara, is possibly interesting because it is a typically Vedic expression - the sacrifice becomes food for the devas for instance, or it can refer to Soma which both feeds the devas, and inspires the ṛṣi. However we must temper this suspicion by reading it along with SN 46.2 which compares the way the five hindrances are sustained by the 'food' of e.g. careless attention (ayoniso manisikāra) to 'signs' (nimitta), with the way that the body is sustained by food: i.e. the metaphor is simply a reference to eating, and probably not a reference to Vedic metaphysics in this case. The latter is the verb used in the rain simile which is found in many other places, but notably in the Upanisā Sutta (SN 12.23) taken by all commentators to date as the locus classicus of the Spiral Path (though I would say it should be AN 11.2!). The root is √pṛ 'to fill' used in the causative form pūreti 'to cause to be filled' and with the prefix pari- here most likely indicating 'completeness' so that paripūreti means 'to fulfil, to complete, to perfect'. We also have the action noun paripūri 'filled up, fulfilled'. So these two metaphors - feeding and fulfilling - give an insight into the nature of idappaccaya, and into paṭiccasamuppāda.

The kind of progression here, though linked to the more typical Spiral Path imagery, is also typical of some texts which talk about the bojjhaṅgas - the bodhi-factors - particularly the suttas of the Bojjhaṅgasaṃyutta (SN 46). Indeed we can see the bojjhaṅgas in this context as another distinct formulation of progressive conditionality.

So these two suttas are drawing together material from a number of different formulations of the path: Spiral Path, ānāpānasati, and the bodhi-factors. And presenting them as a sequence to be followed. This kind of progressive path seems to be typical of Buddhism even beyond the early Buddhist texts - Buddhism is a path. Later in the development of Buddhist thought the path metaphor is replaced by other metaphors which emphasise being rather than doing. These constellate around the notion of the tathāgata-garbha which itself draws on Brahmanical ātman 'contained within the cave of the heart'. My (untested) opinion is that doctrines like tathāgata-garbha (and aspects of Yogacāra) had to be innovated partly because the Spiral Path teaching was lost. The loss of the Spiral Path left Buddhists wondering how liberation could be possible for the deluded, grasping and hating individual.

Notes

- My current list of Spiral path texts includes:

- Samaññāphala Sutta (DN 2; repeated at DN 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 )

- Dasuttara Sutta (DN 34)

- Vatthūpama Sutta (MN 7; repeated at MN 40)

- Kandaraka Sutta (MN 51)

- Upanisā Sutta (SN 12.23)

- Pamādavihārī Sutta (SN 35.97)

- Pāṭaliya Sutta (SN 42.13)

- Nandiya Sutta (SN 55.40)

- Parisā Sutta (AN 3.96) – partial to samādhi only.

- Vimuttāyatana Sutta (AN 5.26)

- Mahānāma Sutta (AN 6.10)

- Satisampajañña Sutta (AN 8.81; truncated at AN 7.65, AN 6.50, AN 5.24 & 5.168)

- Kimatthiya Sutta (AN 10.1 = AN 11.1)

- Cetanākaraṇīya Sutta (AN 10.2 = AN 11.2)

- Paṭhama-upanisā Sutta (AN 10.3 = AN 11.3)

- Dutiya- & Tatiya-upanisā Suttas (AN 10.4 & 10.5; = AN 11.4 & 11.5)

- Avijjā Sutta (AN 10.61)

- Bhavataṇha (AN 10.62)

- Dutiyamahānāma Sutta (AN 11.12)

- Visuddhimagga (Vism i.32)

- Samaññāphala Sutta (DN 2; repeated at DN 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 )

- craving for becoming in AN 10.62 only.

I

I  I

I