Time has almost completely obliterated these disputes. We no longer talk about them because, in the tumult of medieval India following invasions by various foreign powers (notably including Huns and Persians), most of the opposing voices died out. Indeed, broadly speaking we now have just two competing Buddhist theories of karma: Theravāda and Yogācāra. Arguably the Yogācāra philosophers did actually win their dispute with Nāgārjuna, whose own theory of karma is recorded but seldom, if ever, mentioned. They did not win the argument with, for example, the Vaibhāṣikas (aka Sarvāstivādins). Those sects whose opponents died out did not feel the need to keep the disputes alive, even when they are recorded in Canonical texts like the Kathavatthu. So nowadays Buddhists present one or other Theory of Karma as a given. And no one really expects Theravādins and Mahāyānists to agree on anything except the lowest common denominator, so arguments between them are of little interest. Since there is no real challenge to Buddhist ideas, the presentations of karma tend to the formulaic and simplistic. Although some sectarians are still hawks, most moderns are doves who overlook the historical divisions and focus on common ground (i.e. the lowest common denominator) in order to portray Buddhism as one big happy family.

Buddhist morality is rooted in a single, powerful idea that is found almost all human cultures: the universe is moral (cf A Moral Universe?). However, the Moral Universe Theory (MUT) is constantly challenged by unfair experiences: good that is (seemingly) punished, or at best ignored; and evil that is (seemingly) rewarded or ignored. This is a huge problem for all people who believe in a MUT and stretched to breaking by the idea of an omniscient and omnipotent God. First and foremost the Theory of Karma is an attempt to explain the Buddhist MUT, to show how the universe can be moral and morally fair, despite the ubiquitous experience of unfairness. In order to make a MUT workable, most cultures have invoked a post-mortem reckoning, sometimes literally a tally of good and bad deeds, sometimes a weighing of the soul, sometimes the judgement of a moral god, and in the case of Buddhism the impersonal integrator of deeds, karma. Morality is generally seen in accounting terms (See also Moral Metaphors).

Theories of Karma argue that a karma, an action with moral significance, occurs when one has an intention (cetanā) and acts on it (Cf AN 6.63). The final result (vipāka) of karma is experienced primarily as renewed being after death (punarbhava), also known as rebirth; or secondarily as a sensation (vedanā). I've already written a number of essays on the difficult problem of connecting actions to final consequences across time, what I call the Problem of Action at a Temporal Distance. This is usually achieved by a series of intermediate moments of mental activity, citta, that condition each other. The series persists until the initial impulse has achieved its aim (punarbhava or vedanā) or until the momentum has been exhausted. Alternatively the karma produces a kind of potential citta, which has the quality of vasana 'abiding' and is likened to a seed (bīja) that lies dormant until it is appropriate for it to ripen. Variations on these themes are found.

Theories of Karma argue that a karma, an action with moral significance, occurs when one has an intention (cetanā) and acts on it (Cf AN 6.63). The final result (vipāka) of karma is experienced primarily as renewed being after death (punarbhava), also known as rebirth; or secondarily as a sensation (vedanā). I've already written a number of essays on the difficult problem of connecting actions to final consequences across time, what I call the Problem of Action at a Temporal Distance. This is usually achieved by a series of intermediate moments of mental activity, citta, that condition each other. The series persists until the initial impulse has achieved its aim (punarbhava or vedanā) or until the momentum has been exhausted. Alternatively the karma produces a kind of potential citta, which has the quality of vasana 'abiding' and is likened to a seed (bīja) that lies dormant until it is appropriate for it to ripen. Variations on these themes are found.

Buddhist theories of karma specify certain axioms:

- mental activity can only happen one citta at a time, though each citta may be accompanied by a number of concomitant cetāsikas.

- The present citta is conditioned by the immediately past citta, and is a condition for the subsequent citta.

- Cittas can be either kuśala, akuśala or avyākata (wholesome, unwholesome, indeterminate)

- A kuśala citta cannot directly follow an akuśala citta and vice versa.

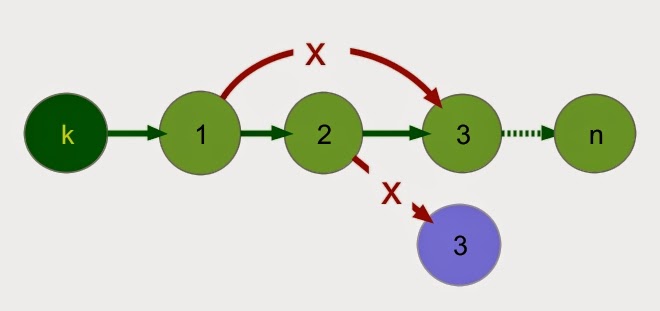

We can diagram these axioms like this (below). The diagram shows that the result is a highly linear, serial process, with no provision for branching or changing the nature of the sequence.

These axioms do not all derive from experience. Meditators report that in the rarefied mental activity of samādhi, mental events appear to occur one at a time, although what applies to an altered state of consciousness does not automatically apply to ordinary waking consciousness. And what presents itself to awareness is not the whole of our minds. The axioms about conditions and sequence, by contrast, are a priori abstract principles which reflect theories about how the mind ought to work, but which are opaque to experience. Like ancient Indian knowledge of human physiology, these early attempts at psychology have mainly historical interest. Here, however we will attempt to take Buddhist arguments on their own terms. We are not subjecting ancient knowledge to modern validity criteria in this essay (I will be doing so in the next essay). In this essay we will stipulate these axioms and work through the logical implications of them.

Explanations of karma are overwhelmingly presented in terms of a simplified model in which there is a single karma giving rise to a single stream of cittas and a single result.† It is assumed that the model will naturally scale up and remain valid, though as I will show below this assumption breaks down as soon as we consider more than one karma. Sometimes an allowance is made for the accumulation of karmas, but even then the model is presented in such a way as to imply that the process is simple. We will begin with the simplest case and see where it leads.

Let us say that karmaa produces cittaa1, and then, in series, cittaa2, cittaa3 up to cittaa(n), where 'n' can be any number. The final cittaa(n) in the sequence, at time n, can be understood in two ways. Firstly it might be just another of the same kind of citta as all the previous cittas and we can see it as exhausting the last of the momentum of the karma. Secondly it might be that cittaa1 up to cittaa(n-1) are just placeholders (vasana) with no real world effects and all of the consequences are bound up in the arising of cittaa(n) which delivers the full impact of the karma. We take this to be true, for example, for all those karmas which contribute to rebirth, but do not have other consequences. Variations on both options have been adopted by different schools and almost all explanations of karma adopt some variation on this model.

A Two Karma System.

Consider what happens if we perform karmab and set off a new stream, cittab, while the cittaa stream is still active. Here we are assuming that we can ignore all other mental activity for the sake of argument, though this would not be a valid assumption, we will address this below. If, according to axiom 1, we can only experience one citta at a time, then the a. and b. streams of cittas must find a way to share our minds. The most efficient way of doing this would be to alternate a1, b1, a2, b2... and so on. In this case, however, it would not be possible to argue that the stream of a cittas still forms an unbroken conditional sequence: cittaa2 is not longer a direct condition for cittaa3 because cittab2 has intervened. Therefore the model violates axiom 2 and has already broken down. It is vital for karma theory that no other citta intervenes in the conditioned process or the continuity is lost. The Theory of Karma does not survive scaling up from one to two active karmas.

|

| © 2006 by Sidney Harris |

For the sake of argument let us accept this possibility that the mind somehow keeps track of streams of cittas from different karmas (keeping in mind that we have accepted an unlikely and weak argument). What if karmaa is kuśala and karmab is akuśala? The result would be alternating kuśala and akuśala cittas, which is forbidden by axiom 4. The Theravādins considered this possibility and added an ad hoc rule that if a kuśala citta is in danger of being followed by an akuśala citta then a non-sensory resting-state (bhavaṅga) citta must intervene. Bhavaṅga cittas are avyākata. Unfortunately, as the Sarvāstivādins pointed out, this was not a solution to the problem because there's no more reason to accept that an avyākata citta can follow a kuśala citta, than to accept that an akuśala citta can. The axiom boils down to "like follows like" and thus the ad hoc interposition of bhavaṅga citta is not a solution, because avyākata is unlike either kuśala or akuśala. So even if the mind can keep track of cittas associated with different karmas, there is no way to accommodate axiom 4. But without axiom 4, karma becomes incoherent: results might end up being unlike their conditions.

The Sautrāntikas also saw this problem. Their solution was to propose that karmas did not produce active cittas until the final moment in time when the karma manifested its results. Until that point the effects of the karma existed only in potential form (vasana), like a seed (bīja). Just as a seed only germinates when there is warmth and water, karma only ripens when the conditions are right. This agricultural metaphor was enormously popular in ancient India and is invoked in all kinds of contexts. Here it amounts to an ad hoc, black-box rationalisation. It begs many questions, not least of which is, if the karma is a metaphorical seed, then what is the metaphorical granary in which it is stored? There is no existing category of process or entity which has this kind of function so yet another ad hoc addition must be made to the theory. Early Buddhism seems to have lacked the metaphor: THE MIND IS A CONTAINER. Early Buddhists also treated mental activity as an entirely transient (anitya) phenomenon, and had a well developed critique of any entity which was considered to persist beyond the existence of the conditions for its existence. There was nowhere to store karma.

The ideal of a "potential citta" is deeply problematic. How does it exist beyond the conditions which gave rise to it (specifically the karma)? How can it have no real-world effects and then at the last moment suddenly have a real world effect? How does it know when to become active? If an entity has no real world effects, how does the real world have effects on it to make it ripen? Many Buddhists were content to have an apposite metaphor, but a metaphor is not an explanation, and in this case the metaphor explains nothing.

The passive/active distinction ought, by extension of axiom 4, prevent one from producing the other because active and passive cittas must be different by nature (svabhāva, used in the earlier sense of defining characteristic). This problem is solved in some karma theories by the ad hoc addition of another kind of conditionality. This special form of conditionality allows a potential-type citta to give rise to an active-type citta (we experience the latter as vedanā, but not the former). In Theravāda theory there is a special ad hoc category of mental activity which occurs at only at the moment of death (cuticitta) and performs the black-box function of transmitting, instantaneously across any intervening space, all of the information about our active karma-processes to the being experiencing punarbahava, via another ad hoc category—relinking mental activity (paṭisandhicitta)—so that the baby is conceived and born in a realm appropriate to the actions of the deceased. Those who believed in an antarābhava argued that crossing space takes time, and described an interim between death and rebirth (I have discussed at length in previous essays). The antarābhava is one massive ad hoc black-box add-on to karma theory, whose main purpose was to explain how karma survives death.

Amongst those who did not go down the 'series of cittas' route of solving the problems associated with karma the most prominent are the Vaibhāṣikas. The Vaibhāṣikas earned their nickname, Sarvāstivāda, because they proposed that a dharma (a broader category that includes citta) caused by a karma, exists and is efficacious as a condition affecting both mind and body only in the present, but beyond the present it exists in a form that can only be perceived by the mind as a resultant citta (this axiom replaces axiom 2). Thus they argued (vāda) that dharmas always exist (sarva-asti), but are only sometimes effective. Arguments immediate sprang up about what was meant by "the present". Like the Sautrāntikas, the Sarvāstivādins have not solved the problem, they have only shunted it down the track a little. The sarva-asti-vāda does not explain how dharmas remain inactive for long periods of time until fruition. The most pertinent response came from Nāgārjuna, who complained that any dharma that did not cease when the conditions for it ceased violated the more fundamental principle of conditionality. In the formula imasmiṃ sati idaṃ hoti... imassa nirodhā idaṃ nirujjhati, when the condition ceases the effect must also cease. Thus anything caused by a karma that persists after the karma has ceased is tantamount to a permanently existing entity. It was presumably this logic that sent the Theravādins and others down the route of a series of cittas.

Nāgārjuna's own solution is that actor, karma, vipāka and sufferer are all just illusions: there are just flows of phenomena, and entities are like foam on water etc. On a relative level (saṃvṛti-satya) we see entities as existing, but at the ultimate level (paramārtha-satya) they do not exist (aka The Two truths). This highly abstract approach to karma satisfies many of the objections we've seen, but as Nāgārjuna's critics pointed out, on the basis of his own favourite text (Kātyāyana Sūtra), to argue that these things don't exist is no more appropriate than arguing that they always exist. Buddhaghosa agreed to some extent that no actor, but only actions could be found. What neither man managed to explain, was how morality made any sense whatever in an illusory world, filled with illusory 'beings', doing illusory actions, and reaping illusory consequences. Such a world is simply nonsensical and Nāgārjuna seems to have lost the argument over karma in pretty short order, so that despite the persistence of Madhyamaka sects into the present, most Mahāyāna Buddhists do not cite Nāgārjuna as an authority on karma, they cite Vasubandhu.

Vasubandhu is responsible for the most famous of all ad hoc black-boxes in Buddhist, the 'storehouse' for storing karmic potential: the ālayavijñāna. Commentators seem to think that Vasubandhu himself, following his Sautrāntika inspirations, considered the ālayavijñāna as a metaphor, but apparently his successors hypostatised the metaphor and came to believe that it represented an entity. As an entity it breaks the fundamental Buddhist axiom disallowing permanent entities. Even as a metaphor it fails, precisely because it is ad hoc and a black box, and as such explains nothing. The ālayavijñāna comes to be associated with tathāgatagarbha, which quite openly equated with ātman in some late Buddhist texts. And thus some Buddhists simply capitulated to the need for an enduring entity to make sense of karma and the afterlife, despite the deep contradictions entailed. We've seen that such is also the case for arguments about the interim realm (antarābhava), mind-made bodies (manomayakāya) and gandharvas.

Multiple Karma Systems

Multiple Karma Systems

However, so far we have only talked about a system of two citta streams. Consider that in each moment we are capable of forming an intention and acting. Theoretically we are capable of 1000s of karmas in an hour, 10's of 1000s in a day, and millions in a year. Of course not every action is karmic, and we don't produce karmas in every moment. Many moments are taken up with vipāka rather than karma. But potentially we can produce many millions of karmas across a life-time, most of which persist until our death when they exhaust themselves as conditions for a new being. It is very likely that an adult human will have millions of concurrent karma-initiated citta-streams operating at any given time.

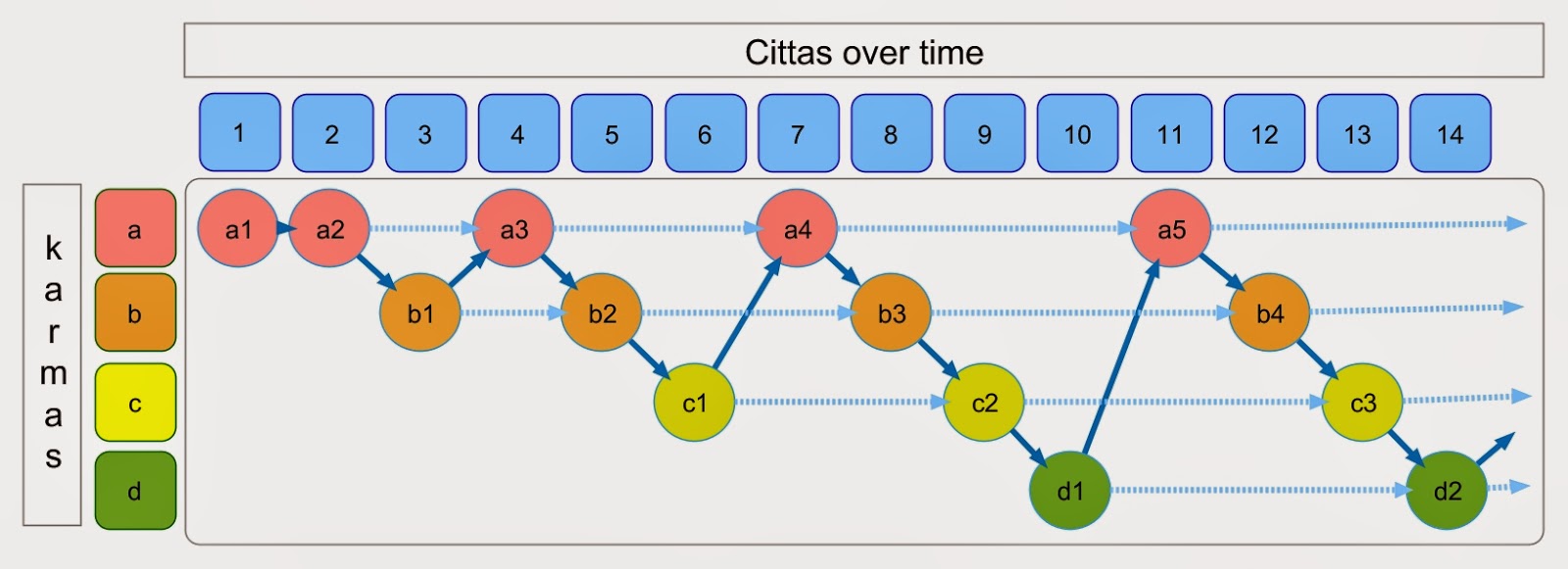

In this diagram a new karma is successively added after the second moment of each citta stream. Each stream must continue to generate new cittas of the same kind in a connected stream, but in order that all the streams can be accommodated they occur in the mind in an arbitrary sequence. Because each citta is a condition for the next, it's less and less likely that the subsequent citta will be in the same stream and not a parallel stream. The sequence here is:

In order to work out the precedence and order of cittas demanded by this situation (which is forced on us by the axioms of karma) we would have to add more ad hoc rules, since there is no order inherent in the model (the order shown above is entirely arbitrary).

In a two citta system the time duration between cittas of the same stream doubles (on average). From cittaa1 to cittaa2 is on average two moments. For every new karma we add to the model, the time between two cittas of the same stream increases geometrically. If a million karmas were active, which is easily conceivable, then the average time between moments of the same citta-stream would be a million moments. Depending on how we count moments this might be as long as two weeks, and the chances of two cittas related to the same karma occurring in succession would one in a million. If there are two weeks and a 999,999 other cittas between two cittas of the same stream, then their relationship as conditioner/conditioned has become purely notional. And, as Nāgārjuna correctly points out, any delay might as well be forever, because it violates pratītyasamutpāda.

In order to work out the precedence and order of cittas demanded by this situation (which is forced on us by the axioms of karma) we would have to add more ad hoc rules, since there is no order inherent in the model (the order shown above is entirely arbitrary).

In a two citta system the time duration between cittas of the same stream doubles (on average). From cittaa1 to cittaa2 is on average two moments. For every new karma we add to the model, the time between two cittas of the same stream increases geometrically. If a million karmas were active, which is easily conceivable, then the average time between moments of the same citta-stream would be a million moments. Depending on how we count moments this might be as long as two weeks, and the chances of two cittas related to the same karma occurring in succession would one in a million. If there are two weeks and a 999,999 other cittas between two cittas of the same stream, then their relationship as conditioner/conditioned has become purely notional. And, as Nāgārjuna correctly points out, any delay might as well be forever, because it violates pratītyasamutpāda.

Imagine a mind in which millions streams of cittas were competing to manifest: the result would surely be random mental activity with no relation to what was happening in the present. The world would be utterly confusing, since very few of our cittas could possibly relate to present sense experience. Everything would be disjointed. It would be impossible to make sense of the world, or for the contents of our minds to consistently reflect the world around us. Or if the bulk of the cittas were inactive, then our minds would be blank for weeks on end as our minds churned through inactive cittas one at a time. However we look at this, there would be no way for a Buddhist Theory of Karma, operating on an appropriately human scale, to logically connect intentions, actions and consequences and the rationale for our morality would be lost.

Another problem is that now a citta is conditioned by two previous cittas on most occasions: one in order to allow karma to work, and one to ensure strict sequence is obeyed. This contradicts the axiom that only one citta can be active at a time. In the diagram above, at time moment 11, citta a4 arises on the condition of citta d1 (which is immediately previous in temporal sequence) and citta a3 (which is the most recent in the karma sequence), but the latter is now operating from three moments of time from the past. As time goes on the cittas associated with a particular karma must bridge more and more time: minutes, hours, days, weeks, perhaps years, perhaps life times. We've seen that the Sarvāstivādin solution was to allow this, but that Nāgārjuna pointed it out that it is tantamount to eternalism to allow a citta to exist beyond the moment when its conditions have ceased. There's no way to make past cittas be conditions for present cittas beyond the immediately preceding moment. And if we allow two cittas, then why not three, or arbitrary many? What is to stop karmas producing infinitely many results? Why would the experience of vipāka bring an end to the consequences of any given karma?

A way around this is a form of cummulative conditionality. The Theravāda Abhidhamma proposes that a citta is able to condition the next citta in 24 ways. Note that two pairs of the 24 conditions are identical, but have different names, which is a sure sign of the model being unsystematic and ad hoc. If we allow this, then it's not necessary to preserve the identity of the streams. The main objective of this scheme is to have a weighted average of karma active at the time of death, which acts as the main condition for one's next rebirth. This eliminates the problem of breaking axiom 1 (one citta at a time). On face value it explains how the information about our actions is carried forward and our rebirth is appropriate to our most recent lifetime of actions.

However this is a lossy process, because as soon as the moment is past, the link between consequence and action is lost: cummulation destroys information about individual karmas, just as a water drop loses its identity if it falls into the ocean. Although in some texts we are taught not to expect one-to-one correspondences between actions and consequences, in others there is a precise relation between them, and such correspondence is necessary especially for karma which ripens in this life. As above, we have to be able to logically connect actions and consequences in order to be moral. It must be completely obvious to anyone who looks, that being good leads to benefit and being evil leads to harm. For this to happen we must be able to identify the consequences of actions in this life. Else morality is simply an article of faith. This is the much misunderstood lesson of the Kālāma Sutta for example.

This version of karma certainly explains how karma can accumulate and affect rebirth, but it destroys the direct link between action and consequence. Only sums-over-time and averages count. Being good on average results in a good rebirth, and being bad on average results in a bad rebirth. This loss of connection also eliminates the possibility of karma ripening in this lifetime, unless it is as the immediately subsequent citta (instant karma). In terms of the metaphysics of karma, this is a workable solution. The loss of karma ripening in this lifetime is probably a good trade off for preserving karma more generally (especially at death/rebirth). However in terms of morality it opens the door to calculations and trade offs: I can kill this kitten and, as long as I make appropriate offerings to the monks, I can still come out ahead. Since traditionally Buddhists mostly aim at a better rebirth, they can now consciously do evil and as long as it is balanced out, not expect any painful consequences. Generally speaking Buddhist moralists like to emphasise that we are responsible for all of our actions, that all our actions count, and that all our actions ought to be good. So while workable, in fact this solution is a moral disaster. What's more it undercuts the idealism which fuels the intense practice necessary for liberation.

So when we scale karma models up they fail spectacularly, at multiple points, and across the board. None of the simple models that Buddhists offer as explanations for karma are able to achieve their stated goal. All subsequent attempts to rescue the Theory of Karma have failed. On its own terms karma does not work.

Conclusion

Another problem is that now a citta is conditioned by two previous cittas on most occasions: one in order to allow karma to work, and one to ensure strict sequence is obeyed. This contradicts the axiom that only one citta can be active at a time. In the diagram above, at time moment 11, citta a4 arises on the condition of citta d1 (which is immediately previous in temporal sequence) and citta a3 (which is the most recent in the karma sequence), but the latter is now operating from three moments of time from the past. As time goes on the cittas associated with a particular karma must bridge more and more time: minutes, hours, days, weeks, perhaps years, perhaps life times. We've seen that the Sarvāstivādin solution was to allow this, but that Nāgārjuna pointed it out that it is tantamount to eternalism to allow a citta to exist beyond the moment when its conditions have ceased. There's no way to make past cittas be conditions for present cittas beyond the immediately preceding moment. And if we allow two cittas, then why not three, or arbitrary many? What is to stop karmas producing infinitely many results? Why would the experience of vipāka bring an end to the consequences of any given karma?

A way around this is a form of cummulative conditionality. The Theravāda Abhidhamma proposes that a citta is able to condition the next citta in 24 ways. Note that two pairs of the 24 conditions are identical, but have different names, which is a sure sign of the model being unsystematic and ad hoc. If we allow this, then it's not necessary to preserve the identity of the streams. The main objective of this scheme is to have a weighted average of karma active at the time of death, which acts as the main condition for one's next rebirth. This eliminates the problem of breaking axiom 1 (one citta at a time). On face value it explains how the information about our actions is carried forward and our rebirth is appropriate to our most recent lifetime of actions.

However this is a lossy process, because as soon as the moment is past, the link between consequence and action is lost: cummulation destroys information about individual karmas, just as a water drop loses its identity if it falls into the ocean. Although in some texts we are taught not to expect one-to-one correspondences between actions and consequences, in others there is a precise relation between them, and such correspondence is necessary especially for karma which ripens in this life. As above, we have to be able to logically connect actions and consequences in order to be moral. It must be completely obvious to anyone who looks, that being good leads to benefit and being evil leads to harm. For this to happen we must be able to identify the consequences of actions in this life. Else morality is simply an article of faith. This is the much misunderstood lesson of the Kālāma Sutta for example.

This version of karma certainly explains how karma can accumulate and affect rebirth, but it destroys the direct link between action and consequence. Only sums-over-time and averages count. Being good on average results in a good rebirth, and being bad on average results in a bad rebirth. This loss of connection also eliminates the possibility of karma ripening in this lifetime, unless it is as the immediately subsequent citta (instant karma). In terms of the metaphysics of karma, this is a workable solution. The loss of karma ripening in this lifetime is probably a good trade off for preserving karma more generally (especially at death/rebirth). However in terms of morality it opens the door to calculations and trade offs: I can kill this kitten and, as long as I make appropriate offerings to the monks, I can still come out ahead. Since traditionally Buddhists mostly aim at a better rebirth, they can now consciously do evil and as long as it is balanced out, not expect any painful consequences. Generally speaking Buddhist moralists like to emphasise that we are responsible for all of our actions, that all our actions count, and that all our actions ought to be good. So while workable, in fact this solution is a moral disaster. What's more it undercuts the idealism which fuels the intense practice necessary for liberation.

So when we scale karma models up they fail spectacularly, at multiple points, and across the board. None of the simple models that Buddhists offer as explanations for karma are able to achieve their stated goal. All subsequent attempts to rescue the Theory of Karma have failed. On its own terms karma does not work.

Conclusion

The axioms that Buddhists use to define and delimit the theory of karma mostly derive from of an ideological program rather than resulting from careful study of nature. These axioms force Buddhists into incoherent or self-contradictory positions on karma that can only be addressed by ad hoc extensions and black-box processes. Those that were traditionally added, brought new metaphysical problems and beyond a certain point these are not addressed by the Buddhist tradition.

Simplistic models of karma break down when we add real-world complexity. What holds for one karma does not hold for two, let alone for a realistic number. This is not just poor abstract philosophy. People base their actions and their life choices on these ideas. If the argument presented here is correct, then karma is a poor basis for decision making because it doesn't make sense and doesn't explain how morality works. Furthermore karma is at the heart of Buddhism. As I have shown in previous essays, where there was a conflict between karma and the highly esteemed idea of dependent-arising (pratītyasamutpāda) it was always the latter that was altered to preserve the functionality of karma. Karma is primary. Without karma Buddhism unravels.

From the beginning there were at least two karma stories. One in which everyone is responsible for their actions and through observation of action and consequence can learn to be a better person. The promised reward of good behaviour was esteem and happiness, both in this life and the next. This message was delivered through folk tales, especially in the form of stories of the past lives of the Buddha and his companions and family: the Jātakas. The second story sought to ethicise the afterlife, i.e. to make morality hold over multiple lifetimes, without breaking the axiom of impermanence. This story gave rise to increasingly sophisticated metaphysical speculation. The two were never successfully reconciled, and the metaphysics became a mess of ad hoc extensions and black-box processes that in practice end up obscuring the link between action and consequence.

Initially the problems stimulated debate and doctrinal innovations amongst different Buddhist sects (as we find ample evidence for in our literature). The records of the debates leave us with the impression of a rich diversity of opinion and a lively critical atmosphere. They also supply us with pre-formulated critiques of all the existing models of karma. However, it seems that the impetus for new and better explanations ran out before the problem was solved.

The old question was always, "Karma must work, but how does it work?" Now we find ourselves asking, "How can karma possibly work, and what happens if it doesn't work?"

Simplistic models of karma break down when we add real-world complexity. What holds for one karma does not hold for two, let alone for a realistic number. This is not just poor abstract philosophy. People base their actions and their life choices on these ideas. If the argument presented here is correct, then karma is a poor basis for decision making because it doesn't make sense and doesn't explain how morality works. Furthermore karma is at the heart of Buddhism. As I have shown in previous essays, where there was a conflict between karma and the highly esteemed idea of dependent-arising (pratītyasamutpāda) it was always the latter that was altered to preserve the functionality of karma. Karma is primary. Without karma Buddhism unravels.

From the beginning there were at least two karma stories. One in which everyone is responsible for their actions and through observation of action and consequence can learn to be a better person. The promised reward of good behaviour was esteem and happiness, both in this life and the next. This message was delivered through folk tales, especially in the form of stories of the past lives of the Buddha and his companions and family: the Jātakas. The second story sought to ethicise the afterlife, i.e. to make morality hold over multiple lifetimes, without breaking the axiom of impermanence. This story gave rise to increasingly sophisticated metaphysical speculation. The two were never successfully reconciled, and the metaphysics became a mess of ad hoc extensions and black-box processes that in practice end up obscuring the link between action and consequence.

Initially the problems stimulated debate and doctrinal innovations amongst different Buddhist sects (as we find ample evidence for in our literature). The records of the debates leave us with the impression of a rich diversity of opinion and a lively critical atmosphere. They also supply us with pre-formulated critiques of all the existing models of karma. However, it seems that the impetus for new and better explanations ran out before the problem was solved.

The old question was always, "Karma must work, but how does it work?" Now we find ourselves asking, "How can karma possibly work, and what happens if it doesn't work?"

~~oOo~~

† This simplifying assumption of a single karma giving rise to a single stream of cittas and a single result is very similar to the simplifying assumption made by macro-economists trying to apply the micro-economic theory of supply and demand to a whole economy. They literally assume that the whole economy can be modelled by assuming a single product and a single consumer paying a single price. Clearly this is nothing like reality and as Prof Steve Keen has shown in his book Debunking Economics, this assumption has been repeatedly shown to be untenable.

Bibliography

Anacker, Stefan. (1972) Vasubandhu's Karmasiddhiprakaraṇa and the problem of the highest meditations. Philosophy East and West. 22(3): 247-258.

Hayes, Richard P. (1989) Can Sense be Made of the Buddhist Theory of Karma. [Paper read at the Dept of Philosophy, Brock University]. http://www.unm.edu/~rhayes/karma_brock.pdf

Other observations are drawn from previous essays which can be found under the afterlife tab at the top of the page.

Hayes, Richard P. (1989) Can Sense be Made of the Buddhist Theory of Karma. [Paper read at the Dept of Philosophy, Brock University]. http://www.unm.edu/~rhayes/karma_brock.pdf

Other observations are drawn from previous essays which can be found under the afterlife tab at the top of the page.

.jpg)