This essay critiques one of the central propositions of the Doctrine of Momentariness (kṣaṇavāda), the idea that mental activity occurs in serial, i.e. as a series of moments of mental activity (citta) occurring one at a time.

As I have previously argued, the Doctrine of Momentariness was a response to the problem of Action at a Temporal Distance. Specifically the principle of dependent-arising specifies that conditions must be present for effects to arise, but karma requires that effects arise a long time after the necessary conditions have ceased. The various Abhidharma projects tried a number of solutions to this problem, but the Doctrine of Momentariness was the most widely adopted. In this doctrine, an action of body, speech or mind, is conditioned by momentary (kṣaṇa) mental activity (citta) with a characteristic intention (cetanā). This citta is the condition for the arising of another identical citta. Each citta arises, persists only long enough to be the condition another identical citta, and then ceases.

In theory, this creates an unbroken chain of cittas that link the intention behind actions with the eventual manifestation of the results of the action, usually aggregated as rebirth in one or other of the rebirth destinations (gati) or individually as sensations (vedanā). In practice, I have shown that this model only works in the special case that there is only one action and one effect (The Logic of Karma. 16 Jan 2015). No Abhidharma project conceived of the relationship between such cittas as simple. A certain amount of complexity was required to fulfil the requirements of the doctrine of karma. For example, the Sarvāstivāda proposed four types of conditional relation between cittas, while the Theravāda proposed twenty-four types.

In this essay I will use practical examples to show that a key component of the Doctrine of Momentariness, the axiom that the mind operates one citta at a time, must be false.

In theory, this creates an unbroken chain of cittas that link the intention behind actions with the eventual manifestation of the results of the action, usually aggregated as rebirth in one or other of the rebirth destinations (gati) or individually as sensations (vedanā). In practice, I have shown that this model only works in the special case that there is only one action and one effect (The Logic of Karma. 16 Jan 2015). No Abhidharma project conceived of the relationship between such cittas as simple. A certain amount of complexity was required to fulfil the requirements of the doctrine of karma. For example, the Sarvāstivāda proposed four types of conditional relation between cittas, while the Theravāda proposed twenty-four types.

In this essay I will use practical examples to show that a key component of the Doctrine of Momentariness, the axiom that the mind operates one citta at a time, must be false.

The Perception of Music.

Years ago, I attended a concert of the contemporary music ensemble 175 East with a friend. They performed a work by John Cage in which there were long periods of silence. It was remarkable just how long the players could pause between notes and we the audience could still detect the harmonic context of the note that broke the silence. The human brain has this remarkable ability to process notes so that they are not simply perceived as isolated events. Each note we hear becomes part of a context for the other notes so that when we hear them, we construct a musical event rather than simply a noise event. "Music" is what happens in our heads when we hear a bunch of notes and mentally construct relations between them. There is a condition is called amusia, in which this ability is lost through brain damage. People with amusia cannot hear the music in the series of notes arriving at their ears. To them, music is just random sounds.

Roughly speaking, the first note in a musical passage establishes a harmonic base (also called the tonic note) and subsequent notes are heard as having a relation to the tonic, as well as to each other. The relations are referred to as harmony. Through choosing the notes that are played together or in a sequence, the composer invokes a particular harmonic "texture", which in turn evokes an emotional response in the listener (and the player). These "textures" can be difficult to articulate directly. Music is often described using visual metaphors like "bright" and "dark". Sometimes we just talk about emotional responses we have and attribute them as intrinsic properties in the music, as in "the music was sad". The range of possible harmonic combinations is very large, so a good deal of subtlety can be conveyed.

More complex music juxtaposes progressions of chords and melody. Or a passage may have more than one melody running concurrently providing counterpoint, which is a term for complex harmonic textures that result from the interplay of two concurrent harmonic textures interacting. We experience this is a very specific way, but mainly we talk about it in metaphorical terms or in terms of how we feel in response to the music. For some people listening to music conjures up images, though this is not universal.

Other aspects of music, such as dynamics, tempo, rhythm, and timbre, work together with melody and harmony to produce a potentially infinite range of music experiences. The all important aspect of tension and resolution in music depends on the relation between the note we are hearing now, the first note we heard in any particular passage, the note previous to the present one, and our expectation of what the next note might be. We sense increasing tension when notes follow that would be dissonant when played at the same time. We sense increasing resolution when the notes would be consonant.

Consonance and dissonance are to some extent objective. The physics of sound and pitch mean that some frequencies blend well together because of reinforcing or cancelling overtones or harmonics. Each note produced by a musical instrument is in fact a complex combination of the main note and combinations of higher pitches from what is called the harmonic series.

The harmonic series was discovered by Pythagoras. It occurs on a guitar string for example when you divide the string length by integers: 2, 3, 4... The main mode of vibration of a string has a maximum amplitude at the centre (1/2) and two mimina at either end (0 and 1). This is called the fundamental mode. The next mode has two maxima at 1/4 and 3/4 of the string length and minima at 0, 1/2, and 1. This first harmonic mode vibrates at twice the frequency, as has a pitch one octave above the fundamental. The next harmonic mode divides the string into three, has a frequency 3x the fundamental and a pitch of one octave plus a fifth. And so on.

When plucked a guitar string will vibrate in a number of these modes at once, producing a complex waveform. Which modes are prominent depends on the materials of the strings and the guitar body, the space it is being played in, and (at least to some extent) the mind of the person hearing it. The presence of combinations of harmonic modes in a musical instrument produces the distinctive timbre of the instrument. and is also responsible for the objective part of why notes are consonant or dissonant in relation to other notes. In woodwind instruments different timbres are produced by the source of vibrational energy: lips (trumpet and other brass instruments), single reed (saxophone, clarinet) or double reed (oboe, bassoon); and the bore of the chamber, which can be a straight-sided cylinder (clarinet, flute), or conical (cornet, saxophone). Some brass instruments combine a mostly cylindrical bore, with a flaring conical end section.

The tonic itself and the octave are the most consonant pitches with respect to any tonic: these have the same frequency and double the frequency respectively, and the octave is one of the main overtone pitches in any musical note. The next most consonant is the perfect fifth, with a frequency of 1.5 times the tonic. The third, with a frequency of 1.25 times the tonic, is also consonant. The most dissonant notes are the minor second (one semitone up) and the major seventh (11 semitones up or one semitone down from the octave).

Consonance and dissonance are to some extent objective. The physics of sound and pitch mean that some frequencies blend well together because of reinforcing or cancelling overtones or harmonics. Each note produced by a musical instrument is in fact a complex combination of the main note and combinations of higher pitches from what is called the harmonic series.

|

| Wikimedia |

When plucked a guitar string will vibrate in a number of these modes at once, producing a complex waveform. Which modes are prominent depends on the materials of the strings and the guitar body, the space it is being played in, and (at least to some extent) the mind of the person hearing it. The presence of combinations of harmonic modes in a musical instrument produces the distinctive timbre of the instrument. and is also responsible for the objective part of why notes are consonant or dissonant in relation to other notes. In woodwind instruments different timbres are produced by the source of vibrational energy: lips (trumpet and other brass instruments), single reed (saxophone, clarinet) or double reed (oboe, bassoon); and the bore of the chamber, which can be a straight-sided cylinder (clarinet, flute), or conical (cornet, saxophone). Some brass instruments combine a mostly cylindrical bore, with a flaring conical end section.

The tonic itself and the octave are the most consonant pitches with respect to any tonic: these have the same frequency and double the frequency respectively, and the octave is one of the main overtone pitches in any musical note. The next most consonant is the perfect fifth, with a frequency of 1.5 times the tonic. The third, with a frequency of 1.25 times the tonic, is also consonant. The most dissonant notes are the minor second (one semitone up) and the major seventh (11 semitones up or one semitone down from the octave).

The physics of making and combining notes is fascinating. But it does not explain music. Music can be analysed as certain physical events in the world, but cannot be reduced to those events since music is dependent on our minds. When we hear music we are exercising a mental ability to parse the relationship between the notes and linking these emotional responses over time. The amazing thing is that we can comprehend the music in a series of single, spaced-out notes of different pitch, durations etc, just as well as if they had been played all at once. Of course the ability can be honed with practice and learning, but all humans have this innate ability to ability to perceive a series of notes as music.

Something very similar happens when we process language, i.e. a series of vocal sounds is decoded into words with grammar and syntax. If we did not hold the whole sentence in our minds until the end we would not be able to relate subject to verb to object. While words convey some meaning on their own, the basic unit of communication is the sentence, which exists over a period of time, not in the present moment. If we just "lived in the present moment", we not understand either music or language.

Something very similar happens when we process language, i.e. a series of vocal sounds is decoded into words with grammar and syntax. If we did not hold the whole sentence in our minds until the end we would not be able to relate subject to verb to object. While words convey some meaning on their own, the basic unit of communication is the sentence, which exists over a period of time, not in the present moment. If we just "lived in the present moment", we not understand either music or language.

Cognition and Time

music requires us to hold recently past sensations in mind, whilst simultan-eously juxtaposing present sensations with those past sensations, and at the same time to form an expectation of what sensations might come next.

The ability I'm describing is related to a function of the brain known as working memory. The way working memory facilitates our perception of music is quite a complex and I'm going to largely gloss over the details. If you are interested a good place to start is this blog post, Music in working memory. Even without knowing the details, it's clear that in order to experience sounds as music requires us to hold recently past sensations in mind, whilst simultaneously juxtaposing present sensations with those past sensations, and at the same time to form an expectation of what sensations might come next. And to process the emotions evoked by the music as we construct it. Similarly with language. This observation was made by the phenomonologist Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), but I came across the idea by way of an article on Abhidharma theories of mind by Monima Chadha (2015).

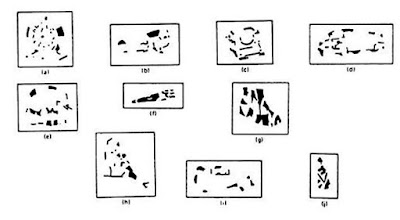

The element of anticipation is easily overlooked by a recent blog by science writer, Rolf Dengren ( @DengrenRolf) emphasises the role of expectation in perception. Dengren uses this example of degraded images to make the point. Take a look at these images and see if you can tell what they are.

Most people looking these degraded images for the first time cannot make out what they depict. However, once they are told what the images depict, then they can make them out. A list of what these are images of is included at the bottom of this page. I was astonished at how obvious these images are once I knew what to look for.

Anticipation plays a big role in music also. The thrill of music often comes when the melody goes off in an unexpected direction, for example by repeating a melody with variations, or by changing key (i.e. changing the actual or implied tonic note) so that the expectation of the listener is confounded. This experience can even be quite thrilling.

One of the basic ideas of Buddhism is that time can be divided into present, past, and future. In one sense this is our basic intuition about time. It feels like we occupy a present, while memories tell us that time has passed, and imagination predicts future events that have yet to manifest. In fact time is not inherently directional, we experience it as moving in one direction because the early universe was extremely low in entropy and is gradually accumulating entropy. So when we compare our present to our memories, we see events occurring asymmetrically: whole things break all the time, but never spontaneously go from being broken to being whole. This as the so-called arrow of time. And it causes us to form certain expectations of the future. It also means that we can usually tell when a film is being played backwards - the action does not conform to our expectations. So "past" and "future" seem like a natural categories to us. And in fact these are much less problematic than the idea of the "present".

Trying to define "the present" is clearly very tricky. The definition of the present involves the shortest conceivable time interval, in the Indic terminology, the kṣaṇa. If everything, every phenomenon, is by definition impermanent, then any phenomenon which lasts for more that a single moment threatens to undermine this definition. It almost inevitably leads to the conclusion that the maximum length of time a phenomenon can persist for, is a single moment. And the definition of a single moment must be squeezed down to the smallest conceivable duration. In my essay, Buddhism and Existence (17 Jun 2016), I explained that an arisen phenomenon cannot be described as existing in Buddhist philosophy, because existence always implies permanence. The fact that an arisen phenomenon must cease at some point means that existence can not be applied to it. So for Buddhist doctrine there is an even greater pressure to say that the present cannot extend beyond the smallest conceivable unit of time. The smallest conceivable unit of time these days, the Planck time, is about 10-44s, though practically speaking we can measure time to a precision of about 12 attoseconds (1.2 × 10-17s).

However, this approach to time is far from useful or coherent. "The present" is a subjective experience which emerges from our interactions with the world over time. The "present", that is the present as it is experienced by a human being, our present, is certainly not a moment in time. It's a subjective experience of time passing constructed in relation to sensate experience, memory and imagination. And in relation to a first person perspective that includes a sense of location in time and space and ownership over experience and actions.

In a way it is strange that Buddhists should emphasise this particular structure of subjective time, because one of the key meditation experiences is the cessation of perceiving time passing. The fact that time stands still while we meditate, but continues to pass in the world around us, ought to have have been an important datum in the attempt to understand the world. Events continue to flow, even when we do not experience them as doing so. In fact the same happens when we fall asleep - we go to sleep at night, but wake in the morning. Time has passed without our being aware of it. The subjectivity inherent in the experience of time ought to have been obvious to Buddhists. More so when we add that the key Buddhist experience is the reduction or elimination of the first person perspective on experience, which (according to anecdote) removes the sense of being firmly located in time and space, and the sense of ownership of experience. So a Buddhist theory of time in which, in effect, the ego is the point of reference in relation to experience is something of a contradiction.

On the other hand, at least one sutta (SN 22.62) seems to be saying that talking about past, future, and present is only a linguistic convention (niruttipatha, adhivanacapatha, paññattipatha) in relation to the skandhas. Still, even in this this linguistic interpretation the present is still conceived of as a single moment in time.

What the perception of music and language shows, is that our awareness includes a present moment, but is not limited to that moment. Awareness is smeared out over time both in the sense of holding past moments in mind and of anticipating the future. If it were not, we couldn't experience music or language. In all likelihood we could not experience change of any sort if our awareness of time were not smeared out.

Critiquing Momentariness.

Our ability to process sounds as music or language demonstrates that the axiom that the mind processes one citta at a time is false. In fact we have to hold many things in mind and our perception of time is not limited to a single moment, but relies on extension over time; whilst also anticipating future moments. This is the minimal requirement for a mind which can comprehend music, language, or change. Far from being momentary, the subjective "present moment" is extensive over a period of time. The very concept of a moment in time as described by the Doctrine of Momentariness is doubtful. The "moment" is a rather arbitrary notion with no objective counterpart.

In my essay The Logic of Karma (16 Jan 2015) I outlined some criticisms of the Doctrine of Momentariness (kṣaṇavāda) with respect to karma. I showed that the doctrine can only work in a mind in which there is only one active karma and no other tributaries to the stream of mental events. Once we try to model two or more karmas or other sensory inputs, the model cannot maintain continuity between condition and effect. All the descriptions of the model I've seen, use the example of a single citta stream. The Doctrine of Momentariness was invented in order to provide continuity between action and consequence under the condition that the absence of the condition requires the absence of the effect. I have shown, the doctrine cannot sustain the required continuity in any real world scenario. It can only work in the special case that there is only one intention giving rise to one outcome (vipāka) - in any given lifetime!

In the current critique, based on how we perceive music or language, we see that one of the fundamental axioms of the Buddhist model of the mind—i.e. the one citta axiom—is flawed in such a way as to invalidate the model. Cognition simply cannot be confined to the present moment or it would not work the way that it does. The whole idea of the "present moment" is flawed.

We can now see that in order to solve the continuity problem, not only is our perception of time necessarily extended over many moments, but the mind would have to process many (very many) cittas simultaneously in parallel in order to allow karma to work in the traditional sense. And this still requires the Abhidharma idea of cittas with multiple properties (cetasika) and multiple kinds of conditional relation between cittas. And this is working within a framework in which we stipulate the traditional idea of karma, when in fact there are many challenges to this conception.

We can now see that in order to solve the continuity problem, not only is our perception of time necessarily extended over many moments, but the mind would have to process many (very many) cittas simultaneously in parallel in order to allow karma to work in the traditional sense. And this still requires the Abhidharma idea of cittas with multiple properties (cetasika) and multiple kinds of conditional relation between cittas. And this is working within a framework in which we stipulate the traditional idea of karma, when in fact there are many challenges to this conception.

Conclusion

I have now shown that the Doctrine of Momentariness is false in two distinct ways. Firstly, in my previous essay, The Logic of Karma, I have shown that the Doctrine of Momentariness cannot provide the continuity required by karma (even though facilitating this continuity is the raison d'être of the doctrine).

Secondly, observations of mental activity related to music and language show that it cannot operate one citta at a time. It is common enough for meditators to report that in states of deep absorption that thoughts, if they do arise, appear to arise slowly, one at a time. I take this quite seriously, however I dispute the interpretation.

The problem here is the process of reasoning from an experience in an altered state to an ontology (a universally true statement about what exists or the nature of reality). When we do this, we almost always get it wrong. Buddhists, for example automatically assume that experiences in meditation are more real that ordinary waking experiences. One can see why this might be. We're taught from the beginning that meditation will lead us to experience reality; or indeed the true nature of reality. Meditation experiences, like drug experiences, often seem hyper-real (or more real than waking experience) and thus it seems logical to assume that they are in fact more real; that in having an experience in meditation we have experiencing the true nature of reality. And since absorption involves us being cut off from our normal sensory stimulation, if we are experiencing "reality", then by the logic of Buddhist doctrine we must be experiencing it directly. Also in that state whatever we experience is ipso facto real. Based on the kinds of assumptions that people absorb along with meditation instruction, these conclusions are logical and intuitive. The problem is that the assumptions that underpin this reasoning appear to me to be false. At the very least they are questionable.

In the clash between traditional Buddhist ideas and modernity, some of us prioritise tradition and some of us prioritise modern knowledge. Part of my project/object is to show that aspects of the tradition, such as the Doctrine of Momentariness, are not coherent even on the tradition's own terms. That is to say, even if we enquire into Buddhist tradition within the worldview of the tradition, ignoring for the moment this clash of cultures, then certain important Buddhist doctrines are incoherent on their own terms.

However, since we do live under modern conditions, since we do have access to objective knowledge about reality, we really ought to take this into account when trying to explain what Buddhists do when we seek awakening; and what really happens when we experience awakening. Buddhist accounts of reality are anachronistic at best. The value of Buddhism does not lie in its medieval ontology. It lies in methods and approaches to understanding experience. Ultimately, it lies in the value of the radical transformation that is characterised by egolessness. What really interests me as a Buddhist intellectual is how we (re)frame these methods and this radical transformation in a coherent and relevant way; especially how we relate it to the domain of objective knowledge about reality. We need to move Buddhist doctrine along from being a collection a medieval anecdotes and metaphysical speculations.

~~oOo~~

Bibliography.

Chadha, M. (2015), “Time-Series of Ephemeral Impressions: The Abhidharma-Buddhist View of Conscious Experience,” Phenomenology and Cognitive Sciences: 14 (3), pp. 543–560.

Update 15 Jul 2016

Study suggests that preference for consonant over dissonant sounds is culturally defined.

McDermott, J. H. , Schultz, A. F., Undurraga, E. A. and Godoy, R. A. (2016) Indifference to dissonance in native Amazonians reveals cultural variation in music perception. Nature [Letter published online 13 July 2016]. DOI:10.1038/nature18635

~o~

Degraded images: a) clock, b) plane, c) typewriter, d) bus, e)elephant, f) saw, g) shoe, h) boy with dog, i) old convertible, j) violin.