In my review of Ji Yun's article on the Heart Sutra (01 June 2018), I noted that, in section 7, in discussing the work of Chén Jiǔchéng 沈九成 (whom he refers to as "Shen"), Ji comments on the mantra as the end of Xuanzang's massive compilation of Prajñāpāramitā texts called Dà bānrě bōluómìduō jīng «大般若波羅蜜多經» (Dà jīng 大經). I noted then:

Ji makes a great deal of the fact that Shen found a mantra at the end of Xuánzàng's collection of Prajñāpāramitā texts that is very similar to the one in the Heart Sutra.... Ji writes about this as "an important discovery" (Ji 40), going to a lot of trouble to reproduce (and correct) the Siddham text from the Taishō page in his article.

In my review, I was more concerned with Ji's self-contradiction in this part of his article than with the implications of this fact. In this post, I will revisit this small point and show that the mantra in question is a late interpolation and thus not very significant when considering the origins of the Heart Sutra.

Note that Xuanzang's text fills three volumes of the Tasihō Tripiṭaka (V–VII). For comparison all the other Prajñāpāramitā translations, including multiple copies of most texts, fill just one volume (VIII).

On the last page (1110) of volume VII (fascicle 600 of 600) of the Dà jīng in the Taishō edition we find two mantras in Siddham script with a Chinese equivalent. They are labelled Bānrě fó mǔ xīn zhòu 般若佛姆心呪 *Prajñā-buddha-mātā-hṛdaya-mantra and Bānrě fó mǔ qīn xīn zhòu 般若佛姆親心呪 *Prajñā-buddha-mātṛpriya-hṛdaya-mantra.

|

tadyathā oṃ gate gate pāragate |

oṃ prajñā prajñā |

The mantra on the left is the familiar Heart Sutra dhāraṇī, with the addition of oṃ and the inclusion of tadyathā (see also Tadyathā in the Heart Sūtra. 13.11.09). It's only Tantric Buddhists that add these features to the dhāraṇī, presumably with a view to making a non-tantric incantation appear to be a mantra. It might appear from this that the mantras are part of the Dà jīng. This is problematic, since Xuanzang the translator was not a tantric Buddhist, and his translation betrays no other influences from Tantric Buddhists.

Another problem is that the accompanying Chinese version is not the standard transcription found in the Heart Sutra (differences highlighted):

T220: 怛耶他 唵 伽帝 伽帝 鉢囉伽帝 鉢囉僧伽帝 菩提 薩嚩訶

T251: 揭帝 揭帝 般羅揭帝 般羅僧揭帝 菩提 薩婆訶。

As far as I can tell, the version of the dhāraṇī from T 220 does not occur anywhere else in the Taishō Edition. This looks like an independent transcription based on the Sanskrit text of Hṛd, created at a time when Tantric Buddhism was ascendent.

The positioning of the mantras is also problematic because they occur after the final line of the text:

時,薄伽梵說是經已,善勇猛等諸大菩薩及餘四眾,天、龍、藥叉、健達縛、阿素洛、揭路茶、緊捺洛、莫呼洛伽、人非人等一切大眾,聞佛所說皆大歡喜、信受奉行。(T 220 7.1110a17-21)

At that time, after the Bhagavān had spoken this scripture, the great bodhisattvas such as Śūravikrāntavikrāmin, as well as the fourfold assembly, devas, nāgas, yakṣas, gandharvas, asuras, garuḍas, kiṃnaras, mahoragas, humans, and non-humans, all the great assembly, having heard what the Buddha had said, were filled with great joy, and faithfully accepted and followed it.

This is followed by a restatement of the title, which is usually the end of a sutra. Thus the spells that follow in Taishō appear to be adventitious, adapted into mantras, and not the same transcription as the Heart Sutra.

The final lines in the Kimura edition of the Nepalese Pañc manuscripts reads

idam avocad bhagavān āttamanaso maitreyapramukhā bodhisattvā mahāsattvāḥ, āyuṣmāṃś ca subhūtir āyuṣmāṃś ca śāriputra āyuṣmāṃś cānandaḥ, śakraś ca devānām indraḥ sadevamānuṣāsuragandharvaś ca loko bhagavato bhāṣitam abhyanandann iti.

āryapañcaviṃśatisāhasrikāyāṃ bhagavatyāni prajñāpāramitāyām abhisamayālaṃkārānusāreṇa saṃśodhitāyāṃ dharmakāyādhikāraḥ śikṣāparivarto nāmāṣṭamaḥ samāpta iti

The Bhagavān spoke thus, and the bodhisattvas, led by Maitreya, the great beings, as well as Elder Subhūti, Elder Śāriputra, Elder Ānanda, and Śakra, the lord of the gods, along with the worlds of gods, humans, asuras, and gandharvas, rejoiced at Bhagavān's words.

The Noble Perfection of Wisdom in 25,000 lines, according to the Abhisamayālaṃkāra, the eighth [sic] section concerning the Dharmakāya is complete.

I think eighth (aṣṭamaḥ) is a mistake for eightieth (aṣṭāśīti). This is followed by two well-known incantations:

ye dharmā hetuprabhavā hetuṃ teṣāṃ tathāgato hy avadat, teṣāñ ca yo nirodha evaṃvādī mahāśramaṇaḥ.

oṃ gate 2 pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā.

It is relatively common for Buddhist manuscripts to use the numeral 2 as a kind of ditto mark. So instead of writing gate gate, they write gate 2. It's interesting that editors preserve this quirk and not others. For example, Buddhist manuscripts almost always write ārya as āryya (which is standard Sanskrit), and bodhisattva as bodhisatva (which is non-standard).

Again, although the mantra is included, it is included after the conclusion and end title. Which means it's not "included in" the text, but rather appended after the end of it. In other words, it's not part of the original text, but was added some time later. That said, since it appears in different witnesses, it seems to have become naturalised.

Other Texts

A mantra is appended to Taishō version of Kumārajīva's Vajracchedikā translation (T 235; 8.7525-7):

那謨婆伽跋帝 鉢喇壤 波羅弭多曳 唵 伊利底 伊室利 輸盧馱 毘舍耶 毘舍耶 莎婆訶

Namo bhagavate prajñāpāramitāya oṃ īriti īṣiri śruta viśāya viśāya svāhā.

The transcription is from Sørensen (2020: 90). (Note that in this article, vajracchedikā is unfortunately mispelled as vajracheedikā throughout).

Where We Don't Find the Mantra

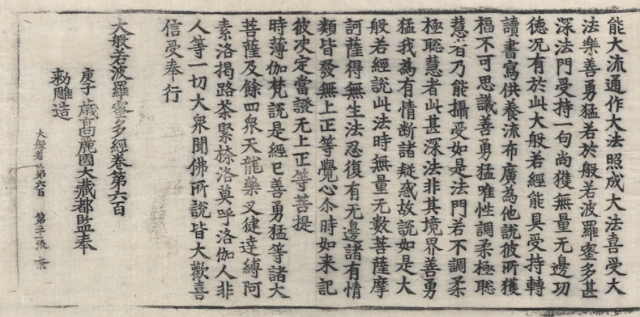

The CBETA version of the canon now includes links to the printed Tripiṭaka Koreana (13th century) which formed the basis of the Taishō Edition. The last page of the Dà jīng clearly has no mantras:

The text here seems to be more or less identical to T 220.

時,薄伽梵說是經已,善勇猛等諸大菩薩及餘四衆,天、龍、藥叉、健達縛、阿素洛、揭路茶、緊柰洛、莫呼洛伽、人非人等一切大衆,聞佛所說皆大歡喜、信受奉行。

大般若波羅蜜多經卷第六百

庚子歲高麗國大藏都監奉勅雕造

The only difference is that the last line refers to the carving of the woodblock: "In the gēngzǐ year (1231 CE), carved by imperial decree at the Dazang Directorate of Goryeo."

There are three other Chinese translations of the Large Sutra:

- Fàng guāng bānrě jīng «放光般若經» (T 221), by Mokṣala (291 CE)

- Guāng zàn jīng «光讚經» (T 222) a partial translation by Dharmarakṣa (286 CE)

- Móhē bānrě bōluómì jīng «摩訶般若波羅蜜經» (T 223); by Kumārajīva (404 CE)

None of these contain the dhāraṇī either.

The Tibetan version of Pañc—Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa stong phrag nyi shu lnga pa. Toh 9—has a lengthy colophon, including a religious poem, but it ends with:

At the time when the carving of the xylographs of this very text, along with those of the Multitude of the Buddhas (Buddhāvataṃsaka), was completed, in the presence of King Tenpa Tsering, the ruler of Degé, the beggar monk Tashi Wangchuk composed these verses at Sharkha Dzongsar Palace, where the wood-carving workshop was based. May they be victorious!

ye dharmā hetuprabhavā hetun teṣāṃ tathāgato bhavat āha teṣāṃ ca yo nirodho evaṃ vādī mahāśramaṇaḥ [ye svāhā]

The Tibetan Aṣṭādaśasāhasrikā prajñāpāramitā (Toh 10) has no mantras or formulas in the colophon

The last page of the Gilgit Pañc manuscript (Karashima et al 2016: 308) has some text following the final samāptaṃ

|

| Gilgit Ms folio 308 verso |

We are fortunate to have a transcription of the colophon by Oskar von Hinüber (2017: 129-130) which consists of the title of the eighty-second (and final) chapter (line 9), followed by four lines, and some interlineal notes, that record the names of the donors who sponsored the copy (many of whom have royal titles).

|| ʘ || prajñāpāramitāyām akopyadharmatānirdeśaparivartaḥ dvyaśītimaḥ samāptaḥ || ʘ ||

10: deyadharmo yaṃ mahāśraddhopāsaka mahāgakhravida nā(ma)siṃhasya. sārdhaṃ śrī deva paṭola ṣāhi vikramādityanandinā. sārdhaṃ śrī paramadevyā torahaṃsikayā. sārdhaṃ śāmīdevyā saharaṇamālena.

11: sārdhaṃ devyā surendrabhaṭṭārika(y)ā sārdhaṃ devyā di + (ysa) puṇyena. sārdhaṃ mātunā nāmasukhena. sārdhaṃ bhrātunā khukhisiṃhena. sārdhaṃ dāya cicīena. sārdhaṃ rājñī tejaḍiyena. rājaḍiena.

11a: sārdhaṃ gakhragavida śupha(rṇe)na.

12: sārdhaṃm maysakka jendravīreṇa sārdhaṃ kṣatra (s.) + pūrena. sārdhaṃ mahāsāmanta gugena. sārdhaṃ gakhravida titsena. sārdhaṃ mahāsāmanta la(tn)anena. sārdhaṃ sarena. sārdhaṃ burohida drugilena.

13: sārdhaṃ pariśuddhabuddhakṣetropapannena + + + + + lvāsena sārdhaṃ pitunā śāmathulena. sārdhaṃ utrasiṃhena. sumasteṇena. butsena. khavāṣena. śiri. yad atra puṇyaṃ tad bhavatu {sarvasatvā}nām anuttarajñānavāptaye stu

13a: tvetsena || sārdhaṃ maghatī(rena) + + + + + +

Note that the repeating term sārdhaṃ means "together with". For further details one can consult von Hinüber's (2017) article, but for our purposes, this shows that there is no mantra or dhāraṇī appended to the text.

Conclusions

The mantra at the end of the Dà bānrě bōluómìduō jīng «大般若波羅蜜多經» (T 220) is clearly a late addition to the end of the text. This is a minor point, but it was useful to my project to clarify it.

We can see that the later addition of features such as mantras or the Ye dharma formula to manuscripts was by no means unusual. At the same time we see Buddhists adding other sources of good fortune to their texts, such as adding āryya or śrī to the title.

It's easy to forget that, unlike the Pāli texts, the Prajñāpāramitā texts were never canonised in India. That is to say, they never attained a fixed or final form. Rather they continued to be redacted, usually expanded, while there was life in Indian Buddhism. And each community saw the text that they had as "the text".

~~oOo~~

Bibliography

Hinüber, Oskar von (2017) "Names and Titles in the Colophon of the ‘Larger Prajñāpāramitā’ from Gilgit." ARIRIAB XX, 129 - 138.

Karashima, S., et al. (2016). Mahāyāna Texts: Prajñāpāramitā Texts (1). Gilgit Manuscripts in the National Archives of India Facsimile Edition Volume II.1. The National Archives of India and The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, Soka University, Tokyo.

Li, Rongxi. (1995). A Biography of the Tripiṭaka of the Great Ci'en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

Liu, Shufen. (2022). “The Waning Years of the Eminent Monk Xuanzang and his Deification in China and Japan.” In Chinese Buddhism and the Scholarship of Erik Zürcher. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk and Stefano Zacchetti, 255–289. Leiden: Brill. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004522152_010

Sørensen, Henrik H. (2020). “Offerings and the Production of Buddhist Scriptures in Dunhuang during the Tenth Century.” Hualin International Journal of Buddhist Studies 3(1): 70–107.

Whitney, William Dwight. (1950). Sanskrit Grammar: Including both the Classical Language and the Older Dialects of Veda and Brahmana. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press.